Winter 2022 Archives

| Expand All | Collapse All |

| Department News |

ViewUNC-Kings College London Partnership: History at the Forefront of International ExchangeIn 2005, amidst calls for more globalization on US campuses, faculty and administration at UNC began imagining how to expand and deepen our school’s intellectual partnerships abroad. Our own History Department, unsurprisingly, has been at the fore of such initiatives, working with international partners to develop connections overseas to enrich the experience of students, graduates, and faculty at UNC.  Participants not pictured: Nicole Harry. The first official exchange began in 2007 when Christopher Browning and Chad Bryant traveled to London with Dr. Lloyd Kramer to present their work at a joint colloquium entitled “The Nazi Occupation and its aftermath in Central Europe.” Since then, the partnership between history departments at Kings and UNC has been one of creative exchange, long-lasting friendships, and intellectual inspiration. Entire book projects have been borne of the encounters, such as the global endeavor of Borderlands in World History, 1700-1914 edited by Kings’ Paul Readman and our own Cynthia Radding and Chad Bryant (Springer, 2014). Other written collaborations include Walking Histories, 1800-1914, co-edited by Chad Bryant, Paul Readman and Arthur Burns (Palgrave, 2016) and War, Demobilization and Memory: The Legacy of War in the Era of Atlantic Revolutions co-edited by Alan Forrest, Karen Hagemann, and Michael Rowe (Springer, 2016). Joint teaching opportunities have also featured as a highlight of the exchange. In 2015, Dr. Sarah Shields inaugurated faculty teaching exchanges between our departments. Dr. Jim Bjork of Kings served as her counterpart making the trip from London to North Carolina. Shields’ class on the Israel-Palestine conflict instantly drew unprecedented enrollment at Kings and was deemed a major success in piloting faculty exchange centered on teaching. A few years later, Chad Bryant and Uta Balbier hosted the first joint UNC-Kings COIL class (Collaborative Online International Learning), which brought the partnership into the digital age by featuring conjoined, virtual classrooms which enabled educational interaction between students and faculty across the Atlantic. Graduate student exchanges have offered another critical pillar of the partnership . Sometimes, this has taken place in the form of student-forward projects, such as when Oskar Czenzde and Till Knobloch invited graduates at Kings to join their online virtual European History Seminar in 2020. The pair later developed this collaboration into an on-the-ground exchange when they obtained funding to send UNC Graduate Student Kylie Broderick to present her research in London in 2022. In addition to the successes of book projects, faculty exchange, and such student-led initiatives, the running, “flagship” program of our departments’ ongoing collaboration is certainly the UNC-Kings College London Workshop on Transatlantic Historical Approaches. This workshop, now in its 13th year, is a graduate student organized event which offers participants a chance to present their research in the Spring in London and then in the Fall at UNC. Each year, the history departments at our respective universities bring together two graduate organizers to select among a competitive pool of participants, who then get the chance to develop their research, meet new faculty at our partner institution, visit relevant archives in host cities, and receive constructive feedback on their work all while visiting the historic streets of London or the busy quads of Chapel Hill. The collaboration has led to multiple graduate publications, constructive feedback on dissertation work, and ongoing friendships, according to participants. The workshop has surely seen its shares of difficulties, such as in 2020, when graduate organizer Daniel Velasquez oversaw the exchange’s navigation of the Covid-19 pandemic. The successful online workshop that year ensured that the History Department kept its title as the longest-running exchange between the two universities, and longer than any other department at UNC-Chapel Hill, by temporarily transitioning the workshop to an online modality. Most importantly, this ongoing graduate exchange has fostered durable intellectual collaboration between our departments over the course of thirteen years. As Kramer recalls of the initial project vision, he believed “the most productive thing we [felt we] could do was to bring grad students into the equation.” Graduate student participants from past years have agreed wholeheartedly. Nicole Harry, participant in 2022, highlighted the interpersonal advantages of the experience, stating “I loved the UNC-KCL workshop, especially the people I met as part of the experience.” She hopes to build on her links with the KCL community by planning other UNC-KCL related events in the future, such as a dissertation writing workshop for advanced doctoral students at Kings and UNC. In 2022, Kylie Broderick will pilot the workshop into its 13th year, and hopes to continue to build the workshop and our relationship with KCL to new heights. The Call for Papers for this year’s UNC-KCL workshop was just released, and the workshop looks forward to an exciting new year of projects under the theme of “(Dis)Unity.” -Donald Santacaterina On Caroline Elkins’ The Legacy of Violence This Fall, the Department of History and the Center for Middle East and Islamic Studies have launched a groundbreaking lecture series bringing cutting edge historians of the Middle East and Central Asia to campus. The series, entitled “Legacies of the Middle Eastern and Muslim Experience of the 20th Century,“ will extend across the academic year. Its first lecture, held in October, was delivered by Professor Elisabeth Leake of Tufts University on her new book, Afghan Crucible: the Soviet Invasion and the Making of Modern Afghanistan (Oxford, 2022). On November 14, 2022, Professor Caroline Elkins of Harvard University delivered the second talk of the series, entitled “Legacy of Violence: A History of the British Empire in Palestine.“ A conversation I had with Professor Elkins during her visit gives me the opportunity to acquaint our community with both the novelty and importance of the book in the field, as well as the significant and sometimes topical issues and points Elkins raises. Caroline Elkins received her Ph.D from Harvard University and has written or edited four books, as well as numerous articles and book chapters. In 2006, Elkins was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for her 2005 book Imperial Reckoning: The Untold Story of Britain’s Gulag in Kenya, and most recently, she published her wide-ranging and highly acclaimed book The Legacy of Violence: A History of the British Empire. This book offers comprehensive conclusions and critiques of both the past and the present of the British Empire. Elkins traces the contexts and ways in which the British Empire used violence from the second half of the nineteenth century to the period of decolonization that emerged after the Second World War. Her analysis extends beyond East Africa, the focus of her first book, to India, Cyprus, and Palestine-Israel. Throughout this journey, Elkins highlights two important concepts that define the British Empire and the Pax Britannica: liberal imperialism and legalized lawlessness. In fact, as Elkins points out, these are two highly interconnected concepts, with two seemingly contradictory faces. Both concepts highlight where, and under what conditions, violence is an indispensable element of empire. In particular, Elkins incorporates many critiques of empire into her narrative, emphasizing that Britain was a liberal empire, not a fascist one. Here, liberal imperialism put Britain in an exceptional position in terms of its ability to juxtapose reform and violence. Liberal imperialism created its own vocabulary, using terms such as “civilizing mission,” and “trusteeship,” and perceived all colonized societies as both backward and infantile. Thus, liberal imperialism prepared the ground for the moral impact of violence. This liberal project, which also included social reform, incorporated “civilizing” backward societies, following the definition of “good government” by philosophers such as John Stuart Mill. A distinctive characteristic of the British case was that violence and coercion were not only a way of establishing control over colonized communities; they also formed part of a development and progression culminating in independence. At this point, Elkins argues that legal lawlessness is also an important concept in understanding how this ground for the use of violence is prepared. The British Empire did not neglect to provide a legal basis for its actions. Elkins defines these attempts at legalization as legal lawlessness. According to her, the British Empire used the attempt to bring the rule of law to “backward” and “uncivilized” societies as a central idea to justify its actions. In doing so, it legalized practices that had previously been illegal, giving rise to the concept of legal lawlessness. Elkins emphasizes that this legacy of legalized lawlessness should be considered an important contributor to the questioning of democratic defects in many countries of the Global South that are now independent but were formerly under British colonial rule. Such a legacy can therefore be seen to still provide clues to how the British Empire shaped the world today. The ways in which the British Empire remains with us today is a subject of hot debate among scholars and in the public arena. Although the empire seems to have disintegrated as a result of the decolonization period after the Second World War, Elkins states that it is still influential, which we can see in the debates about Brexit and the Commonwealth’s existence today. Even if the Empire no longer exists, British identity is an imperial identity, and this identity profoundly influenced the Brexit debate and its outcome. According to polls, around sixty percent of the UK population says that the Empire provides an identity to be proud of. This identity is also relevant to the Commonwealth, an organization that is inconceivable without the empire, but also about the monarchy’s determination to continue the legacy of the empire in some form. Creating an empire of its own, Britain both influenced the past and continues to influence the present with its legacy. The empire destroyed literally tons of documents, especially those relating to the Mau Mau movement and the concentration camps in Kenya, and had most of the rest shipped to Britain, yet it has not escaped the scrutiny of historians like Elkins. Her answer to the question “Can we see any parallels and similarities between Nazi Germany and the British Empire through Hannah Arendt’s explanation of ‘The Banality of Evil’?” briefly demonstrates how the British Empire should be defined. Although we can see the “Banality of Evil” through the workers in different colonies of the Empire, Britain was not a fascist and totalitarian empire, but a liberal imperial empire. -Burak Bulkan |

| Faculty Spotlight |

ViewNew Faculty Spotlight: Professor K. Antwain Hunter This Fall, the Department of History welcomed Dr. Antwain K. Hunter to its faculty. Professor Hunter is a historian of freedom and slavery, with a focus on North Carolina. In the midst of a busy teaching schedule in his first semester at Carolina, he kindly agreed to answer my questions about his research and background. Why did you decide to become a historian? Connected to this, when did you first encounter history growing up? As a kid, my dad was in the army, and I lived on a military base for part of my youth. As such, I grew up looking at a lot of military equipment and personnel. I saw the tanks that served as decorations on the base, and I watched soldiers ride on a variety of different vehicles to enter their training ground that I lived next to. My brother and I began to read about the Second World War, the American Civil War, and American Revolution. As I got older, I continued to love history, but my interest in the military aspects of it declined. I became more interested in the social questions that arise out of conflict, like the Civil War, for instance, and less so in the war itself. You are currently working on a book, A Precarious Balance: Firearms, Race, and Community in North Carolina, 1729-1865, that examines the dynamics of free and enslaved black North Carolinians’ firearm use before the American Civil War. How did you choose this topic? It’s a great question. I was sitting in a grad seminar, in what I think was the second year of my Ph.D. program. The professor, Dr. William Blair, is retired now, but he was a director of the Richards Civil War Era Center at Penn State. I think he was doing a 19th-century course on Civil War America. He wanted us all to go and look at online databases of sources. Now, of course, you guys are all familiar with them, but this is when they were still new. We were looking at what kind of sources they had in these databases. How do they present it? Are they transcribed? While doing this, I came across this collection that Lauren Schweninger at UNC Greensboro put together. It was a bunch of petitions from or to county courts, basically dealing with court cases that involved enslaved and free people of color. I think there were also some women and children who were basically marginalized people in the court system. And I came across these petitions from white folks in Delaware who were basically petitioning their state legislature that there should be a law requiring free black people to get licenses before they could have guns because they were essentially a threat to public order and safety. And I remember being struck by this: “Oh, this is wild. I’ve never thought about race and firearms in the past.” Scholars have spent a lot of time talking about the ways that 19th-century men have constructed their masculinities, some of which involve firearms. It wasn’t like I hadn’t had conversations in class about guns before, but I never thought about it along those lines. I started digging into it, and the more I got into this topic, the more I found that there was not a lot written, and there was a need for more scholarship that was focused on this because it just struck me as so fascinating. This dissertation project is now the book I am working on. You work on a topic that is very important for understanding the US but is also defined by violence. How do you seek to balance that when teaching students? My research is centered around firearms, and with that comes a great deal of violence. I write and talk about violence committed by and against black folks. And in one of the courses I teach, “American Slavery,” there was just a great deal of violence generally. Slavery was built on violence and sustained by violence. Without violence or the threat of violence, the whole thing falls apart. Teaching these subjects is always a balancing act. When teaching, I always try and make sure that people are aware of violence, as it is a crucial part of understanding all of it. I try not to go into a place where I think that the violence feels excessive in the classroom. Not because the violence was not excessive, but I try to present it in a way that I think people can sit with it. And it might make them a little bit uncomfortable, but it doesn’t push them out. We read and talk a lot about violence, but I also focus on a lot of the other things. Slavery was built and sustained by violence, but slaves were people who also had families. Enslaved people had things they did for recreation. They have religious institutions that they built to have resistance against violence. When teaching, I really try to balance it out that way. With firearms, there is also a lot of violence, but people were also able to sustain their families through hunting, and resisted the violence that their enslavers were projecting onto them. I’m very cognizant of this question, but also not leaving the violence out of my narrative because you can’t tell the story without discussing a great deal of it. What teaching methods do you use to reach students? I taught at a small private liberal arts school in the Midwest for eight years. A lot of my style is really based on a discussion. In class, we will read some texts, and I want to hear what students think about them. I want to see them make connections between what they read in the secondary sources or in some of the primary sources. When leading discussions, I want to see my students put different primary sources in conversation with each other and get them to really grapple with trying to understand these sources as part of a larger narrative. I also really want them to engage with each other. It’s one thing when you stand in front of a room and just talk at them. And sometimes, we need to do that. However, I really want them to take some of the onus to ask each other questions and present their ideas to each other. We want students in history classes to understand the past, ability to engage historical texts, and be able to explain and contextualize them. But we also want them to have some of those liberal arts skills that are not specific to history but learning how to read, write, engage with ideas, and present arguments critically. I think that those discussions and really grappling with primary source documents can really push them to think about some of those things. We are coming up through the end of the semester. What has been your favorite aspect of teaching in North Carolina? It’s still new, and I’m still, in some ways, learning the student body and trying to get to know some of the institutional cultures and things like that. But I will say that the students I’ve worked with are curious and hardworking, and they have been really bright. Some of them are not even majors, but the way that they process, think and engage with information has been really refreshing. I will say that both of the classes I have this semester have been delightful. Of course there are some students who will not do the things they need to do, but generally, I’ve been really impressed with the quality of the undergrads so far. -Mark Thomas-Patterson |

| Alumni Spotlight |

|

View

No items found

|

| History in Our World |

ViewStudents Talk about their Involvement with Traces: The UNC Journal of HistoryEach year, UNC-Chapel Hill history students publish Traces: The UNC Journal of History. First created in 2011 by UNC students G. Lawson Kuehnert and Mark W. Hornburg and supported by the UNC-Chapel Hill Parents Council, the journal features the work of students currently studying history. After over a decade in operation, the award-winning journal – which won Phi Alpha Theta’s prestigious Gerald D. Nash History Journal Prize in both 2013 and 2017 – will be releasing its issue at the end of the Spring semester. For over a decade, Traces has been an important and unique collaboration between graduate and undergraduate students at UNC-Chapel Hill, showcasing the important historical research conducted by undergraduate students.  Traces publishes articles on a diverse range of topics for each issue. This year’s journal will feature articles on medieval history, 19th century history, and the history of psychology. Previous editions have had a similar approach, covering a wide range of geographical areas and thematic topics, including the history of science, gender history, and Indigenous history. The current Editor-in-Chief of Traces is Javier Etchegaray, a Ph.D candidate studying colonial Southern Chile. He first became involved with Traces in Summer 2021, when the journal was facing difficulties due to the Covid-19 pandemic. “It was unclear whether Traces would be able to publish during the 2021-2022 academic year. In this sense, working as managing editor for Traces put me to the test in terms of thinking about organizational resiliency and working toward team-building. The support and trust that the department places on Traces, while remaining an entirely student-run and autonomous organization, is at the heart of a synergic relation that is one of my favorite elements in this project,” Javier said. While the Editor-in-Chief role is taken on by a history graduate student, the other editors are mostly undergraduates, ranging from freshmen to seniors. Joining Traces means that they gain not only valuable editing skills, but they also get to work alongside graduate students. “I got involved in Traces because of my love of history and learning,” Dionejala-Tytionna Q. R. Muhammad, a senior majoring in history and political science, told me. “Through reading the papers that students have submitted, I have opened my mind to new and old stories in history. I am happy to have met the wonderful people of Traces and continue learning more history.” Joining the editorial board at Traces helped third-year history and economics major Omar Ahmed Farrag discover his love of editing: “I joined Traces because I really like to help explain things to others – and while as an editor I knew I wouldn’t be submitting my own papers to the journal, I did know that I would be helping to polish and promulgate papers written by other historians that would explain unknown and necessary histories that might be of benefit to others. What I’ve enjoyed most as an editor is that I have to push the writers to substantiate their claims, learning to deliver constructive and clear feedback to them, so that, most importantly, they employ analysis that doesn’t lose sight of the people and their histories whom they cover.” The journal creates a unique collaboration between undergraduate and graduate students that benefits both. Graduate students who are not teaching, for instance, can join Traces as a way to engage with and edit undergraduate work, while undergraduates gain valuable mentorship from the graduate students involved with the journal. As Javier told me, “As graduate students, we tend to work with undergraduates primarily through teaching. Traces has given me a rather unique opportunity to work with UNC’s undergraduates – and their research – in a horizontal, collegiate, and mutually-beneficial manner. Thus, I consider Traces to be a salient example of service to the field that a history graduate student can carry out beyond the purview of professional organizations.” After working to revitalize the journal after it faced difficulty during the pandemic, Javier is hopeful for its future. “My main assignment with Traces during my time as managing editor has been to ensure the continuity of the journal and reconstitute it as an organization after a COVID-induced lapse. In this sense, I am ready to soon pass this position on and I am excited to see where the journal can go in the future. I would love to see the journal expand the scope of its activities, both thematically and organizationally. While the core of the journal lies in its full-length articles, there is much space for new thematic content to be developed, and this will depend on the creativity of future iterations of the editorial staff. At the same time, I would be elated to see more graduate students working with the journal, both as editors and authors. While most of us dedicate the brunt of our article-writing towards indexed and peer-reviewed journals, I think that a publication such as Traces can allow graduate students to develop more creative styles of writing that otherwise wouldn’t fit with traditional journals.” Traces, then, is a unique opportunity for both undergraduate and graduate students to publish their writing. For over a decade, Traces has been an important venue for celebrating the research of undergraduate students at UNC, while also encouraging a unique collaboration between graduate and undergraduate students. Some of the previous work from Traces can be found on the Carolina Digital Repository, part of the UNC University Libraries system. Traces will be looking for new editors to join the team during the next academic year and encourages both undergraduate and graduate students to reach out about how to get involved. -Tess Megginson |

| Out of the Archives |

|

View

No items found

|

| Graduate Student News |

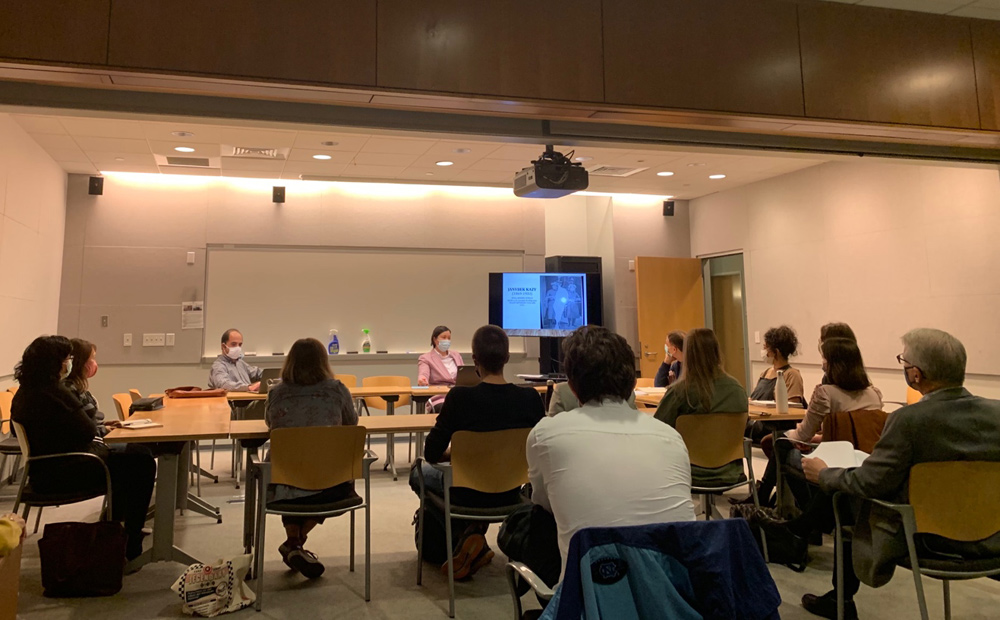

ViewGraduate Student Profile: Alma Huselja’s USHMM Research This past summer, third year Ph.D student Alma Huselja was given the opportunity to conduct research at one of the most significant institutions for Holocaust research, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) in Washington, D.C. From June to August, Alma conducted research on her PhD dissertation, which examines “Aryanization” in the Independent State of Croatia (Nezavisna Država Hrvatska: NDH). After defending her MA in December 2021, Alma was eager to begin researching on a larger scale. “I knew that I wanted to continue on the topic for my dissertation. While I had valuable experience researching in a local archive, to take my research to a larger scale, I needed to look at documents from other parts of the NDH, national-level ministries, and so forth. The issue I faced arose from how spread out the sources are from archive to archive and country to country. The organization of NDH offices means that sometimes sources are not always in the cities you’d expect them to be. That already entails a lot of travel between cities in Croatia and Bosnia. And, since Belgrade became the Yugoslav capital, many documents pertaining to the NDH, like postwar war crimes trials, are kept in Serbia. The logistics and costs, both time and monetary, of visiting these archives over one summer were simply impossible.” At the USHMM, however, Alma was able to access different archives and archival materials from a centralized location. Not only did this help with her research over the summer, but also for planning future research trips. “It was a place where I could conveniently begin my research and get a base of knowledge for what sources are out there. This would help me in preparing my prospectus as well as funding applications for future research,” Alma told me. The previous summer, Alma had traveled to a local branch of the Croatian State Archive in Varaždin to supplement the research she had already conducted with the town’s digitized newspapers and oral histories from local survivors. Since she was researching on a smaller scale for her MA thesis, she was able to take time with each document while at the archive, taking notes and mentally processing the documents as she went through them. At the USHMM, Alma had to learn to take an entirely different approach to tackle the amount of collections she needed to view. Instead of taking time with each document, she had to focus on collecting as many documents as she could while there. Since these will be documents that she will be using not only on her Ph.D thesis, but on projects afterwards, her priority was to collect rather than to fully process. Some of the documents Alma examined were similar to ones she had looked at in Varaždin, but on different levels in the chain of bureaucracy. “I spent a lot of time looking at documents from various levels of the NDH state apparatus. Alongside local-level documents from town councils, there were plenty of collections from the Ministry of Treasury, the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Ustaša Surveillance Service and so on. I was familiar with the town council documents from past research, but the higher-level documents were completely new to me. These also included letters written to each branch of government – whether internal circulars or letters from other individuals. Many were documents detailing the process of expropriation, like trustee contracts and itemized inventories of property and their valuations.” Alma also continued listening to oral histories from survivors and bystanders to violence as well as examining newspapers and cultural organization documents, like those from interwar Yugoslavia’s Jewish communities. Alma also discovered archival connections she had not considered looking at before researching at the USHMM: “There were also documents from archives I hadn’t thought of that I was pointed towards as potentially useful. This included the Russian State Military Archive, which keeps documents captured by the Soviets from the Axis Powers, as well as Israeli archives which collected photographs, letters, memoirs, and testimonies from immigrant Yugoslav Jews.” In this way, the USHMM helped Alma expand her research to archives she wouldn’t have otherwise examined. As Alma continues to process her documents from the summer, she’s looking forward to continuing to write her thesis: “I am interested in understanding what the NDH’s intentions were with this massive expropriation campaign and how people on the ground understood and were affected by the project. The timeline of the NDH’s existence is what draws me to this aspect. The Ustaše [a Croat fascist organization and leaders of the NDH] were marginal during the interwar period, but only within a few months into the NDH’s establishment the genocidal campaigns were well underway. How did so many people get drawn into collaboration and complicity with racialized violence? What were the experiences of victims? And, specifically for my project – how did the mass expropriation and redistribution of property affect societal dynamics and relations? Like elsewhere in Axis Europe, so-called ‘Aryanization’ was a messy process filled with corruption. At the same time, the NDH insisted on bureaucratic mass theft, which I believe tells us something about its intentions with such an approach. It also must have affected how individuals who took property perceived what they were doing. Many were not personally looting homes and businesses, but instead writing requests and filling out forms. How did this affect their understanding of the role they played in the persecution of their neighbors? How did it affect their relationship with the NDH as a state?” Alma’s time at the USHMM helped improve her organizational skills and how she plans her research. Conducting research at the USHMM allowed her to learn how to prioritize which documents she looks at and make schedules to keep her research on track. She hopes to use these skills next year, when she spends the year in Croatia and Bosnia conducting research and begins writing her dissertation. -Tess Megginson Yusuf Sezgin: Historian of Liberation Theology, Rock Music Enthusiast As one of the top graduate history programs in the world, UNC attracts a highly selective group of cutting-edge historians. Our graduate students are brilliant, creative, hard-working, and, unsurprisingly, eclectic. Yusuf Sezgin is a doctoral candidate conducting research for an ambitious history comparing liberationist formulations of Islam and Catholicism in Latin America, Africa, and the Middle East in the 1960s and 1970s. Yusuf spends much of his time poring over the writings of Muslim and Catholic intellectuals, but I learned that he has another passion as well. I recently sat down with Yusuf to learn more about his love of rock. First of all, thank you very much for accepting my interview offer. I do know you are very interested and dedicated to rock music, concerts, and festivals. So, I would like to start with this question: Where does your intense interest in rock music come from? To be frank, I don’t really know. Like everyone else thrown into this world without knowing what’s waiting for us, I had no idea that music would become a very close friend of mine one day. Probably the first rock songs that I came to know were those of Cem Karaca and Barış Manço, who were considered the fathers of Turkish folk rock (namely Anatolian rock) emerging in the 1970s. They were still pretty popular in the early 1990s. My uncle was a fan of Cem Karaca and I can recall him singing Karaca songs to me when I had no idea about who it was. I realized much later that this was ironic because my uncle was a member of an anti-communist nationalist party and Karaca had been prosecuted for his “communist” lyrics, forced into exile, and even stripped of Turkish citizenship in the early 1980s. It struck me that anti-communists can listen to and enjoy songs by communists, or vice versa, as music is most of the time not about pure ideas but something that goes far beyond that and touches the depths of human soul. I don’t have an answer yet as to whether we can separate the art from the artist. So how did your relationship with music continue, what was the course of this relationship? I think it was in the early/mid 2000s when I got enthusiastic about rock music. I had a Walkman, had friends sharing CDs with each other, loved watching music video channels, and then as digital music became much more accessible and enjoyable with the internet, I started to create my first playlists on iTunes. I had already been familiar with some legendary bands such as the Beatles, Pink Floyd, Metallica, and Iron Maiden, but there were some other rock bands/singers from that period that I loved from the outset, such as Coldplay, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Oasis, Evanescence, Green Day, Bon Jovi, Nickelback, and Avril Lavigne. (No, I didn’t fall in love with her, unlike most of my friends). But, to be honest, I was more into mainstream pop. I was a big fan of Backstreet Boys; my favorite song was Blue’s “U Make Me Wanna,” and I very much enjoyed the “Latin explosion” because I had so much fun listening to Ricky Martin, JLO, Shakira and Enrique Iglesias. Looking back today, I can see more clearly that almost all of these names and music movements originated in North America/Britain. I also genuinely believe that music is universal, but as someone who was born and raised in Turkey, a country long struggling with an identity crisis due to being stuck between “the West” and “the Middle East,” it seems a bit strange to me that I cannot name a song from any of the neighboring countries from the same period, such as Greece, Armenia, Iran or Syria. It has for sure something to do with the history of modern Turkey, but I suspect that many people from non-Western countries could tell similar stories, so I think it is also about cultural and economic domination. But I of course can, and in fact should, name a few great Turkish rock bands that emerged in the late 1990s/early 2000s and had a huge impact on my generation, such as Mor ve Ötesi, Şebnem Ferah, and Duman. Have you ever thought about teaching a course on music and world history? Yes, I have been thinking about it lately. The idea of teaching a global history course on the twentieth century sounds super exciting. Music is probably strongly linked to any issue you might like to discuss in a global history course. So, I’ve been saving for a while now any article or book I come across that is somehow related to music and history, whether it be about protest music in Chile, the underground rock scene in Iran, Pan-Africanist Afrobeat, or the transatlantic impact of British post-punk. I really do hope that those would help me one day to design a fun and nice history course. Who are you listening to lately? Has anything changed in your interests in music? What I say will be deeply personal, as what and who we listen to is mostly shaped by our personal histories, taste of music and personal mood. I think I’m now more into alt/indie rock, classic hard rock, and progressive metal. I am a huge fan of Coldplay as I have been listening to them for almost twenty years now. Manchester Orchestra is one of my all-time favorite bands. Their lyricism, cinematic music, concept albums, and live performances are fantastic. There are many classic bands that I love, such as Guns N’ Roses, Queen, Metallica, Led Zeppelin, Bad Company, AC/DC, and Radiohead. There are some other bands, which are relatively younger but also great, such as The Strokes, Shinedown, The Black Keys, and The White Stripes. I would listen to any song Chris Cornell or Layne Staley sings. I sometimes lean more towards progressive/black metal of British/European bands such as Anathema, Leprous, and Opeth. I also follow with great admiration lots of young, rising rock bands such as Greta Van Fleet, Måneskin, The Struts, Cage the Elephant, Dirty Honey, Houndmouth, and Blacktop Mojo. How can rock music relate to academia, or more precisely to humanities and social sciences? I usually tend to intellectualize everything I am interested in, and this often becomes exhausting to the point where I can no longer enjoy those things. And I know this is not unique to me. So, what I do is to use my non-academic interests to explore and start new hobbies. I love music, so I started going to concerts. I started using my camera during shows and became more and more passionate about music photography. But I also occasionally read music history books. The last book I finished reading was Blowin’ Hot and Cool by John Gennari, a fantastic work of history about jazz criticism in the US. I’m not into jazz and know almost nothing about its history, but it is really fun to read something without the pressure to know more about and work on it. I’m also trying to bring music into the classroom. I’ve TA’ed for a “World History since 1945” course this semester, and every week before class started, I played a music video that was related to the discussion topic of the day. I played Bob Dylan’s “Masters of War” (1963) the week we discussed the nuclear arms race, and showed a short clip of James Brown performing in a music festival in Zaire in 1974, the day we discussed Black Panthers and Black internationalism. And one day I just played a clip of Prince playing the final solo of “While My Guitar Gently Weeps,” just because it is so beautiful to watch. I have to give credit here to Dr. Max Owre, because he was the inspiration, and there is no doubt that he is much better at incorporating music into his class, and in very creative ways. I mentioned earlier the difficulty of separating the art from the artist. This is definitely a topic students can relate to. I don’t really know how and what I should feel, if I should feel anything at all, about Michael Jackson, whose song “They Don’t Care About Us” was perhaps one of the first non-Turkish songs I ever listened to. I still love that song. Maybe when a work of art becomes publicly available, it no longer belongs to the artist, but to everyone who connects with it. So maybe we can simultaneously dislike the artist and admire their work. That’s why I sometimes discourage myself from googling an artist whose music I love. But I’m also aware that this issue is almost always about power hierarchies and structural abuse. That’s where it gets complicated, and why it is definitely worth thinking about and discussing. -Burak Bulkan The Carolina Russia SeminarOn Thursday night once a month, the Carolina Russia Seminar is one of the highlights of the calendar for the UNC History Department. Started by Drs. Donald J. Raleigh and Louise McReynolds, its leadership was handed to Eren Tasar in 2017. Dr. Tasar had long understood the value of seminars for his own intellectual development: “When I was in graduate school, my advisor ran a seminar, where Ph.D students usually presented.” Dr. Tasar stated that it is key for young scholars to follow the pulse of research: “It’s very important for our graduate students, especially those planning a dissertation, to learn about the cutting-edge scholarship in the field.” While understanding developments in scholarship is necessary for planning academic work, Dr. Tasar also argues for the importance of community building: “Carolina is a supportive place, and the seminar really is about creating a sense of community for people who study Russia and the former Soviet Union.” This is particularly important as it is often difficult for graduate students to get outside of their own subfields. The seminar creates a space through which UNC graduate students can talk to one another.  Though the presenter lineup strives to bring prominent historians in the field to campus, one of the seminar’s main aims is to help doctoral students in the department, as well as MA students in the Global Studies Program’s Russia concentration, develop professionally. Dr. Tasar stated, “It’s a nice place to workshop ideas which they will later bring on to conferences and try to publish in journals.” This desire is connected back to the seminar’s existence as a comfortable space where students can welcome critique from friendly faces. This sentiment was shared by Ph.D. candidate Alma Huselja, who presented her work titled “‘Citizens and Thieves: Aryanization in Wartime Varaždin, Croatia” in August. “Since I had recently submitted an adaptation of my master’s thesis to a journal and was waiting for the readers’ reports, the seminar was a good way to talk through my ideas and hear helpful critiques on where the paper could be made better.” UNC History Ph.D candidates are not the only people who present at the event. In October, Dr. Stephen Riegg, an Assistant Professor of History at Texas A&M University and recipient of a Ph.D from our department in 2016, presented his work, a potential first chapter for a book looking at the Russian empire’s attempts to control movement in the Southern Caucuses. A longtime veteran of the seminar from his graduate student days, Riegg highlights its importance in his own growth as a professional historian. “As a graduate student at Carolina, I attended the seminar with great interest, not only to learn about other researchers’ work, but also to experience the intellectual vibrancy of a supportive environment from which all of us benefited.” Riegg appreciates the ongoing participation of the seminars’ founders, Drs. Raleigh and McReynolds. “Their expertise as much as their enthusiasm for scholarly discussion makes the Carolina Seminar Series the sought-after intellectual venue it is.” The seminar is not only an intellectual event, a social event as well. The seminars, which are held in the conference room on the fourth floor of the FedEx Global Education Center, are always followed by pizza and drinks, ordered from Dr. McReynolds’ favorite pizzeria, Sal’s. Thanks to the mild North Carolina winters, participants are able to eat, converse and gossip in the building’s outdoor rock garden, even on winter nights. Between bites, students have the opportunity to share impressions about the presenter’s work and engage visiting scholars in conversation. Scholars from other institutions in the area, such as UNC Greensboro, NC State, and Duke, also participate, as do colleagues from the Departments of Economics, Political Science, and Slavic Languages and Literatures. Dr. Tasar notes that running the seminar is not without its challenges. The doctoral program in history at Carolina has long held pride of place in training historians at the cutting edge of scholarship on the Soviet Union and the Russian Empire. It has been a top destination for prospective Russianists for decades. The retirement of the two Russianists who built Carolina’s program in Russian history has created a gap that can only be filled when the History Department hires at least one Russianist. Currently, the graduate program in Russian history is primarily maintained by scholars focusing on Russia’s peripheries: Tasar is an expert on Soviet Central Asia, while Dr. Chad Bryant’s research focuses on modern Eastern Europe. Attendance at the seminar is also impacted by broader changes affecting graduate education in the humanities at UNC, as the department has reduced the cohort of incoming graduate students for several years in a row due to financial constraints. Nevertheless, thanks to support from the History Department and the Carolina Seminars Program, the seminar has maintained a devoted following. The sense of community and solidarity fostered by participants makes the Russia Seminar a cornerstone of the intellectual life of our graduate program. -Mark Thomas-Patterson |

| Undergrad News |

|

View

No items found

|

Gifts to the History Department

The History Department is a lively center for historical education and research. Although we are deeply committed to our mission as a public institution, our “margin of excellence” depends on generous private donations. At the present time, the department is particularly eager to improve the funding and fellowships for graduate students.

Your donations are used to send graduate students to professional conferences, support innovative student research, bring visiting speakers to campus, and expand other activities that enhance the department’s intellectual community.

|

To make a secure gift online, please click “Give Now” above.

The Department also receives tax-deductible donations through the Arts and Sciences Foundation at UNC-Chapel Hill. Please note in the “memo” section of your check that your gift is intended for the History Department. Donations should be sent to the following address:

UNC-Arts & Sciences Foundation

Buchan House

523 E. Franklin Street

Chapel Hill, NC 27514

Attention: Ronda Manuel

For more information about creating scholarships, fellowships, and professorships in the Department through a gift, pledge, or planned gift please contact Ronda Manuel, Associate Director of Development at the Arts and Sciences Foundation: ronda.manuel@unc.edu or (919) 962-7266.