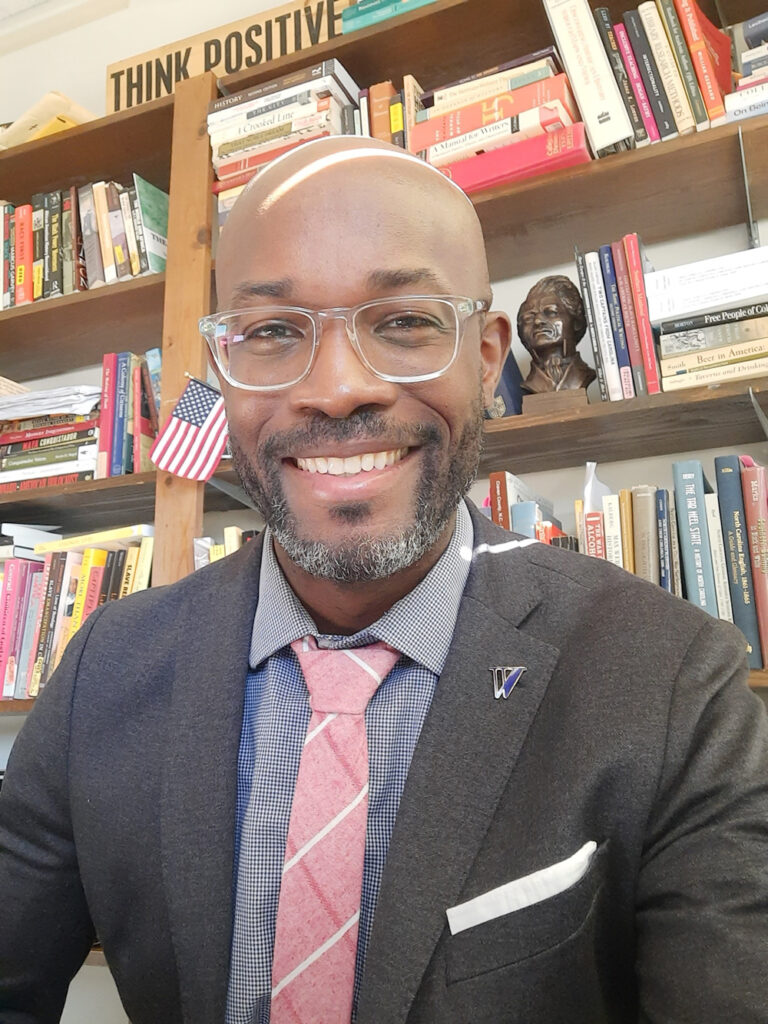

This Fall, the Department of History welcomed Dr. Antwain K. Hunter to its faculty. Professor Hunter is a historian of freedom and slavery, with a focus on North Carolina. In the midst of a busy teaching schedule in his first semester at Carolina, he kindly agreed to answer my questions about his research and background.

Why did you decide to become a historian? Connected to this, when did you first encounter history growing up?

As a kid, my dad was in the army, and I lived on a military base for part of my youth. As such, I grew up looking at a lot of military equipment and personnel. I saw the tanks that served as decorations on the base, and I watched soldiers ride on a variety of different vehicles to enter their training ground that I lived next to. My brother and I began to read about the Second World War, the American Civil War, and American Revolution. As I got older, I continued to love history, but my interest in the military aspects of it declined. I became more interested in the social questions that arise out of conflict, like the Civil War, for instance, and less so in the war itself.

You are currently working on a book, A Precarious Balance: Firearms, Race, and Community in North Carolina, 1729-1865, that examines the dynamics of free and enslaved black North Carolinians’ firearm use before the American Civil War. How did you choose this topic?

It’s a great question. I was sitting in a grad seminar, in what I think was the second year of my Ph.D. program. The professor, Dr. William Blair, is retired now, but he was a director of the Richards Civil War Era Center at Penn State. I think he was doing a 19th-century course on Civil War America. He wanted us all to go and look at online databases of sources. Now, of course, you guys are all familiar with them, but this is when they were still new. We were looking at what kind of sources they had in these databases. How do they present it? Are they transcribed?

While doing this, I came across this collection that Lauren Schweninger at UNC Greensboro put together. It was a bunch of petitions from or to county courts, basically dealing with court cases that involved enslaved and free people of color. I think there were also some women and children who were basically marginalized people in the court system.

And I came across these petitions from white folks in Delaware who were basically petitioning their state legislature that there should be a law requiring free black people to get licenses before they could have guns because they were essentially a threat to public order and safety.

And I remember being struck by this: “Oh, this is wild. I’ve never thought about race and firearms in the past.” Scholars have spent a lot of time talking about the ways that 19th-century men have constructed their masculinities, some of which involve firearms. It wasn’t like I hadn’t had conversations in class about guns before, but I never thought about it along those lines. I started digging into it, and the more I got into this topic, the more I found that there was not a lot written, and there was a need for more scholarship that was focused on this because it just struck me as so fascinating. This dissertation project is now the book I am working on.

You work on a topic that is very important for understanding the US but is also defined by violence. How do you seek to balance that when teaching students?

My research is centered around firearms, and with that comes a great deal of violence. I write and talk about violence committed by and against black folks. And in one of the courses I teach, “American Slavery,” there was just a great deal of violence generally. Slavery was built on violence and sustained by violence. Without violence or the threat of violence, the whole thing falls apart.

Teaching these subjects is always a balancing act. When teaching, I always try and make sure that people are aware of violence, as it is a crucial part of understanding all of it. I try not to go into a place where I think that the violence feels excessive in the classroom. Not because the violence was not excessive, but I try to present it in a way that I think people can sit with it. And it might make them a little bit uncomfortable, but it doesn’t push them out.

We read and talk a lot about violence, but I also focus on a lot of the other things. Slavery was built and sustained by violence, but slaves were people who also had families. Enslaved people had things they did for recreation. They have religious institutions that they built to have resistance against violence. When teaching, I really try to balance it out that way.

With firearms, there is also a lot of violence, but people were also able to sustain their families through hunting, and resisted the violence that their enslavers were projecting onto them. I’m very cognizant of this question, but also not leaving the violence out of my narrative because you can’t tell the story without discussing a great deal of it.

What teaching methods do you use to reach students?

I taught at a small private liberal arts school in the Midwest for eight years. A lot of my style is really based on a discussion. In class, we will read some texts, and I want to hear what students think about them. I want to see them make connections between what they read in the secondary sources or in some of the primary sources.

When leading discussions, I want to see my students put different primary sources in conversation with each other and get them to really grapple with trying to understand these sources as part of a larger narrative. I also really want them to engage with each other. It’s one thing when you stand in front of a room and just talk at them. And sometimes, we need to do that. However, I really want them to take some of the onus to ask each other questions and present their ideas to each other.

We want students in history classes to understand the past, ability to engage historical texts, and be able to explain and contextualize them. But we also want them to have some of those liberal arts skills that are not specific to history but learning how to read, write, engage with ideas, and present arguments critically. I think that those discussions and really grappling with primary source documents can really push them to think about some of those things.

We are coming up through the end of the semester. What has been your favorite aspect of teaching in North Carolina?

It’s still new, and I’m still, in some ways, learning the student body and trying to get to know some of the institutional cultures and things like that. But I will say that the students I’ve worked with are curious and hardworking, and they have been really bright. Some of them are not even majors, but the way that they process, think and engage with information has been really refreshing.

I will say that both of the classes I have this semester have been delightful. Of course there are some students who will not do the things they need to do, but generally, I’ve been really impressed with the quality of the undergrads so far.

-Mark Thomas-Patterson