Spring 2017 – Archives

| Expand All | Collapse All |

| Department News | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

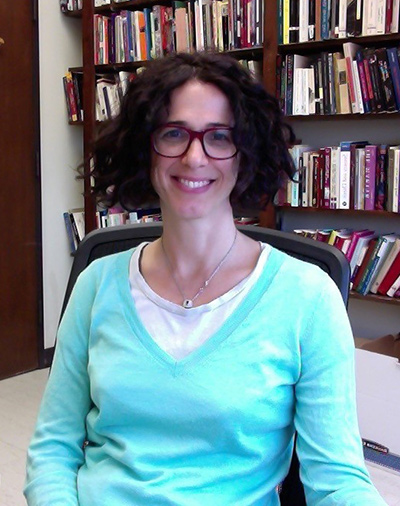

ViewQuiz Bowl Challenges Local High SchoolersThe Phi Alpha Theta chapter of UNC, with support from the UNC History Department, hosted its fourth annual history quiz bowl for high school students on Saturday, April 1st, in Hamilton Hall. Question content roughly followed knowledge from AP-level classes and ranged from the Indus Valley Civilization to Supreme Court nominees and Nagasaki to Tenochtitlan. This year, nine teams from six high schools participated, including Durham School of the Arts, Panther Creek High School, East Chapel Hill High School, Jordan High School, Cary High School, and Chapel Hill High School. After ten matches, Durham School of the Arts, whose team name was Society of the Harmonious Fists, and Chapel Hill High, whose team name was the Black Tigers, had the most points and continued on to the Final Match, which was read by Professor Lisa Lindsay. After an initial tie in this match, Durham School of the Arts won the day. The Quiz Bowl Organizing Committee is composed of undergraduate volunteers from Phi Alpha Theta, history majors, and history enthusiasts from other departments. Around fifteen talented and dedicated students began composing questions in August in order to write and edit a total of 561 questions by April. –Ellie Edwards ’17, President of UNC Phi Alpha Theta

New Issue of Traces Explores Memory and Southern History

–Sarah Miles and Garrett Wright, Editors-in-Chief Prizes, Honors, Accolades

Graduate Student Teaching Awards

Faculty Awards

Graduating History MajorsThis month, we say goodbye to our seniors, who are heading off to a wide range of professional opportunities and graduate programs. And students who are returning to Carolina in the fall have exciting summer plans. What has a history major prepared them to do? They can tell you themselves:

The Undergraduate Program

One indicator of the deep involvement of history students in research is their continued success in receiving grants from the university to pursue research projects. The Office of Undergraduate Research awards about sixty Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowships (SURFs) each year. Although one might think that students in the sciences would dominate such awards, history students consistently apply for, and are awarded, SURF grants—more so than those from comparable departments like English, Religious Studies, or Anthropology. Between 2003 and 2016, fifty-seven history students were awarded SURF grants. Nearly all of these were members of the senior honors program, undertaking summer research in advance of writing senior theses in history. Numerous history courses (27 by current count) are classified by the Office of Undergraduate Research as “research exposure courses,” meaning that they include at least one fully realized research assignment. These include courses on modern Eastern and Central Europe, Lumbee history, the Atlantic slave trade, the modern Middle East, North Carolina history since 1865, and oral history. In addition, several other history courses are designated as “research intensive courses,” in which at least half of the course is devoted to students conducting original research and presenting research conclusions. One set of research intensive courses is the History Department’s capstone for history majors, the “Undergraduate Seminar in History” (numbered HIST 398). Each semester, approximately ten such seminars are offered. Limited to fifteen students, the seminars are taught by renowned faculty, who guide participants through the research and crafting of significant, original historical scholarship. In spring 2017, HIST 398 seminars include “Sports and Politics in the US,” taught by Matthew Andrews; “Nazi Germany,” by Konrad Jarausch; “Comparative Environmental History,” taught by Cynthia Radding; “Rome 154 BC-14 CE,” taught by Richard Talbert; “The Crusades,” by Brett Whalen; and “Modern European Intellectual History,” by Lloyd Kramer. In these courses students start by becoming familiar with major trends in the existing historical approaches to their topics. Then they formulate research topics of their own, drawing on resources available in UNC’s extensive library and archival collections, as well as elsewhere. They are taught how to search for materials, how to organize their notes in database software and other ways, how to structure their evidence in the service of their own interpretations, and how—step by step—to craft a compelling, clear, and even elegant piece of historical writing. The results are often stunning, both to faculty readers and to students who could not fathom at the start how they would rise to such an intellectual challenge. Papers produced by students in these classes have been published in Traces, UNC’s award-winning history journal, as well as in other undergraduate history journals. In Melissa Bullard’s Fall 2016 HIST 398 on Florence, cradle of the Renaissance, Rachel Holcomb ’18 researched and wrote an essay on fifteenth-century Florence’s humanistic ideals portrayed through architecture. Her article on the subject has been accepted for publication in the May 2017 issue of The Michigan Journal of History. The UNC History department awards the author of the best HIST 398 paper of the year the annual Josh Meador Prize at the department’s spring reception. In 2016-17, a record-breaking eleven papers were esteemed so excellent that they were nominated by the professors who supervised their production. –Lisa Lindsay, Director of Undergraduate Studies |

| Faculty Spotlight |

ViewBenjamin Waterhouse takes us through The Land of Enterprise

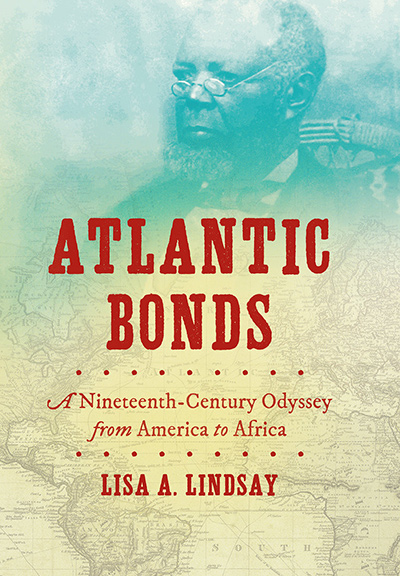

In his first book, Lobbying America: The Politics of Business From Nixon to NAFTA (Princeton University Press, 2013) as well, Waterhouse used business and economics to understand broader political and social themes in American history. Perhaps this is a product of the factors that led Waterhouse to the historical profession. He had planned on going to law school. However, a few months in France dissuaded him. “I guess the decision was basically made because there were just so many things I didn’t know.” He was enticed by academia not because he dreamed of being a professor, but because he couldn’t figure out any other way to spend time thinking about the ideas and issues that frustrated him. “Trying to do it on my own certainly wasn’t working,” Waterhouse said. “I just felt more and more confused.” Upon arriving at Harvard for graduate school Waterhouse studied with Lizabeth Cohen and was interested in the work on conservatism Lisa McGirr had just published in Suburban Warriors. Initially he had considered doing a comparative history of social movements in France and the United States in the 1960s. However, as that project fell apart he turned to an examination of the Business Roundtable, a lobbying organization. This allowed him to get at the issues of conservatism and society that were at the heart of his intellectual preoccupations. And it allowed him to integrate historical questions about business with questions about labor, consumption, consumerism, politics, and people. The Land of Enterprise is a trade press book aimed at a general audience. Waterhouse offers an accessible and compelling narrative that encourages readers to rethink the standard presentation of American history by placing business and economic development at the center of the story. “When we talk about national character or American ideas, there’s this element of free enterprise and entrepreneurship and innovation,” Waterhouse said. But, “when we tell the story of the nation’s history, it’s as though those economic forces disappear.” The Land of Enterprise provides a response by taking well-known historical events like the Civil War or the Iran Hostage crisis, and integrating business and economic development into the story. Turning to the turbulent world of business, Waterhouse demonstrates how the pursuit of wealth and economic development is crucial to American history. Writing for a popular audience poses challenges, but more importantly it provides an important opportunity to engage with the public. As academics, Waterhouse said, “we make our understanding of the past more accurate by making it more complicated.” While this makes writing a synthetic survey challenging, it also enables historians to encourage more nuanced understandings of people and society. “My hope is that somebody reading this has a more expansive sense for what business is,” Waterhouse said, “so that nobody would say something as simple and silly as, “You know, “I’m against business,” or “I’m pro-business,” or “I’m anti-union,” or “I’m pro-free market.”” Waterhouse hopes that readers will come away understanding “that these are just empty categories.” The Land of Enterprise is an important work that pushes back against the notion that business and economics operate in a separate sphere in American history or American public life. Waterhouse resists the notion that the state is an autonomous, separate “thing” that can either help or hurt the market. By confronting the complexity of the relationship between business, economics, politics and society, The Land of Enterprise presents an innovative interpretation of American history. –Danielle Balderas Professor Lisa Lindsay’s New Book is a Truly Transatlantic Biography

“This is the rare back-to-Africa success story,” Lindsay explained. “Vaughn didn’t come as part of a big colonizing mission, he didn’t come with guns blazing, and he also didn’t come expecting to be received into the motherland with open arms. He went, I think, with a very realistic notion: it’s going to be tough, but I’m going to do what I can to make a living and make connections, and stay alive.” Lindsay describes Atlantic Bonds as a “contextualized biography” of Church Vaughn. This means that Lindsay connects Vaughn’s story to the major historical trends that shaped Nigerian, American, and Atlantic world history. Vaughn was involved in the wars that fed the slave trade, worked for missionaries, and experienced the early years of British colonization. He later led an anti-racist revolt against some missionaries and founded a prosperous business. His descendants were among the first generation of anti-colonial nationalists in Nigeria. All the while, Vaughn and his descendants exchanged letters with their relatives in the United States. This allows Lindsay to present a multi-dimensional Atlantic world story. “The fact that they had these parallel family trees, and that they kept in touch, enabled me to tell a story that compared his life and times in Africa with his relatives in the United States,” Lindsay said. “One of the surprising things that comes out of this is that life was much better for Vaughn than for his relatives in South Carolina before and after the Civil War, and really until the 1920s and 30s.” Taking an Atlantic world approach led Lindsay, who was trained as a colonial Africanist, into unfamiliar scholarship, including histories of South Carolina and of the great migration. Her background as an Africanist, however, gave her a unique perspective on this scholarship. “Coming from another field, I think U.S. history looks different than if you come at it from inside U.S. history,” Lindsay explained. Through Vaughn’s story, Lindsay makes important claims about slavery and freedom. First, she demonstrates the ubiquity of slavery in the Atlantic world, as Church Vaughn moved from one slave society to another. Even in Liberia, African Americans who left the slave society of the United States replicated the institutions they had fled. Lindsay also shows that slavery and freedom existed on a spectrum. “There were lots of shades of unfreedom, or shades of labor exploitation and dependency, in between, and just because someone wasn’t legally a slave didn’t mean that they weren’t subject to those things. And Church Vaughn, in fact, was never a slave or never a slaveholder himself, but he was involved in lots of points along the spectrum,” Lindsay said. In many ways, Atlantic Bonds was an ideal second book for Lindsay, who has long been interested in the connections between Africa, the United States, and the rest of the world. “I first got interested in Africa when I was a college student in the late 1980s building shanties against apartheid on my university campus and listening to African pop music that was becoming available in the United States at that time. And so between political activism and being interested in music, I got interested in Africa. But I got interested in Africa via its entanglements with the rest of the world.” –Aubrey Lauersdorf Flora Cassen Asks Tough Questions about Antisemitism and Race

After reading an article on yellow badges and hats in Venice, Cassen was inspired to pursue research in Jewish Studies on symbols and marking. Rather than working on Venice or another major urban center, Cassen concentrated her attention on the northwestern peninsula of Italy. This decision proved fruitful for two reasons. There was an incredible amount of material about Jews and badges in the archives. Furthermore, Cassen recognized, “the kind of Jewish society that I found was very different from Venice, Florence, or Rome which were the communities that had the most history written about them and were the best known.” Rather than Jewish communities attempting to solve problems together, Cassen encountered a family here, a family there, in which she saw individuals trying to deal with diverse situations. When asked how she would give an elevator pitch about her forthcoming book, Cassen light heartedly asked, “Can it be a high building?” Joking aside, Marking the Jews in Renaissance Italy is a compelling account of discrimination and resistance. It is a study of the Jewish badge in the northwestern corner of Italy during the 15th and 16th centuries. Cassen explained, “At regular intervals during those two centuries authorities tried to force Jews to wear a yellow badge,” and, later on, a yellow hat. Her book tries to untangle administrative motivations, Jewish responses, and importantly, what it tells us about Jewish life and Jewish-Christian relations in those areas at the time. Cassen grappled with concepts of race and discrimination in writing the book. While she acknowledges that there is a professional undercurrent that resists talking about race in the premodern era, she insists “If there’s one group that was treated as a different race without being one, it was the Jews.” By the 15th century, Cassen argues, Jews were seen as radically different to an extent that was not bridgeable through conversion. “So what I argue is that it [marking] is an attempt to fully and completely define Jews as such, as utterly and radically different. Literally in their blood in a way that cannot change or improve. And then I also argue that Jews understood that.” Becoming marked by signs and symbols contributed to the process of racializing Jews, Cassen argues. At the heart of Marking the Jews in Renaissance Italy is a reflection on the connection between antisemitism and racism. “Race is something that at least today is defined as a physical feature, whereas religion is something you choose. I’m showing that it’s not always so obvious.” There was an attempt to define Jews as a culture, as a people, and as a religion, “as radically and indelibly different from Christians.” However, by excavating the history of that process, Cassen goes on to argue that eventually it did not work because the authorities were unable to make the badges permanent. “Even though it was an attempt to indelibly mark the Jews as different,” Cassen said, “because of the resourcefulness of Jewish communities and the many overlapping powers and conflicts between them, it never fully succeeded.” Cassen would like readers to come away understanding “how members of small, minority communities can live and negotiate a kind of life even in difficult circumstances.” “It’s not perfect,” she argues, “but they figure out a way.” Lastly, Cassen is hopeful that her book will encourage people to reflect “on what it means when groups of people are in some ways identified and defined by other groups in a negative way and how that works. And the possible consequences of that.” –Danielle Balderas Cemil Aydin on The Idea of the Muslim World

Aydin’s new work was inspired by his first book, The Politics of Anti-Westernism in Asia: Visions of World Order in Pan-Islamic and Pan-Asian Thought (Columbia University Press, 2007), which was a comparative history of Pan-Islamism and Pan-Asianism. He tried to make sense of the fact that ideas of Asian or Muslim solidarity emerged at the peak of Western hegemony. This led Aydin to recognize that the ideas of Asia, Africa, and the Islamic world did not pre-exist and respond to European colonization. “They actually co-constituted themselves,” Aydin explained. “They emerged in conversation through the contradictions of the legitimacy of empire.” As Aydin started thinking about his new project, he began by looking at the afterlife of Pan-Islamism, Pan-Asianism, and Pan-Africanism in the Cold War. “I faced this puzzle among the three pan-nationalist ideologies,” Aydin said. While Pan-Asianism and Pan-Africanism largely faded away, Pan-Islamism did not. “It re-emerged in the form of political Islam and ideologies that say Muslims should follow neither the capitalist West nor the socialist East–that they should create their own modern path.” But, as Aydin notes, “It also emerged because it was inspired by the re-racialization of Muslims on a global scale–in Europe and America.” While there was the initial phase of racializing Muslims through religion from the 1870s to 1930s, Aydin explained that with decolonization one might assume that racialization would disappear. However, the racialization of Muslims picked up steam in the late 1970s, 80s, and 90s, “and that’s the moment we are living with right now,” Aydin said. These historical observations led Aydin to ask, “How did the Muslim religion become a race again?” The Idea of the Muslim World works through this question by looking at how the racialization of Islam was quite different under imperial rule because it was racialization within the empire. He explains why categories of racialization that emerged in the age of empire persisted, albeit in different forms, throughout the Cold War. By looking to geopolitical diplomacy, Aydin is able to analyze the intricacies of global politics. He finds continuity and change over the 150-year period he studies. For instance, Aydin see parallels between the Ottoman-British alliance before WWI, and the Saudi-American alliance in the Cold War. The US encouraged the development of a Pan-Islamic identity as a counterweight to Soviet influence in the Middle East. However, Aydin notes, “As the Ottoman-British alliance turns anti-British in World War I, this time Saudi-American Pan-Islamism turns anti-American in the 1980s.” Aydin hopes his book will encourage readers to reflect on how racialization by religion can take different forms, with a particular set of assumptions attached to each. One of the biggest challenges Aydin encountered in writing The Idea of the Muslim World was contesting the narrative that Islam and Christianity have been at war with each other since day one. “It helped me to think about the narratives we live with and how we can work together with colleagues and other intellectuals to offer a different narrative,” Aydin reflected. Teaching and speaking with audiences about his work has cultivated a sense of professional and civic duty. “We have to think about our mission and public engagement more broadly and not see universities as isolated from the wider political and social forces of society.” Aydin hopes his book will reach a general audience. Aydin is insistent that he wants to empower his audience. For readers in Europe and America, he hopes “this will make them understand that they are complicit in producing some of the things they think they are fighting against.” And for readers in the Middle East and elsewhere, Aydin wants them to recognize that political Islam and Pan-Islamic internationalism were not inherited from early Islamic history, but were a product of the imperial and decolonization experiences. “In a way, history will empower them to express and formulate their quest for justice in languages that will not trap them with the categories that racialize them in the first instance.” –Danielle Balderas |

| Alumni Spotlight | ||

ViewPhillip England ’67 Reflects on How Studying History at UNC Influenced His Life and Career

Where did you grow up and why did you choose to come to Carolina? “My family believed in education and UNC was considered to be and is in fact a leading Southern school. You didn’t run into many people in South Carolina who had graduated from UNC so it seemed special. In those days, Chapel Hill was a relatively small university with about 8,000 students. In the South, Carolina was considered equivalent to schools like Dartmouth and Brown. That’s why I came to UNC, and I have had a career I couldn’t have dreamed of because of it.” Can you share a fond memory you had as a history student in the 1960s? “I cannot describe the feeling you had in those days at the university. First of all, it was small enough that you could easily walk across the entire campus. There were no bus lines or parking decks so you walked wherever you needed to go—downtown, the bookstores and to have dinner at the Carolina Coffee Shop. In fact, there was a sign on the cash register there that said, ‘limit $10 on checks—good or bad.’ It was a marvelous world. On Friday nights, some of the history students would go to the Rathskeller on Franklin Street for drinks and to talk about history. I especially remember going to Professor Frank Ryan’s office and noticing that he had bookcases to the ceiling filled with books. When I asked why, he said, ‘I’ll never be able to read them all but I just feel comfortable having them here.’ That was the impression that Chapel Hill made and that’s why in my mind it’s still a superb place.” At UNC, did you have a favorite professor or take any classes that have influenced your career? “I can still remember my professors in three dimensions; they made that kind of powerful impression on me. I can remember the way they looked and dressed even. Studying in Chapel Hill under them awoke in me a desire to see the great world, and it proved to be a great world. In my career, I have worked on Great Britain’s income tax treaty, and it was Dr. Barbara Schnorrenberg who taught me British history and inspired a lifelong interest in the subject, particularly 19th century British history. One of the major initiatives in the Clinton administration was Central Europe, and it was Dr. Kraehe who taught me Austrian and German history. I have worked on Brazilian and U.S. tax treaties; Dr. Federico Gil taught me Latin American history. I’ve also helped with French treaties and have litigated in the courts of Taiwan and other countries; I remember to this day my history professors and what they taught me. Professors sometimes have no idea of the profound impression they make on a student’s life and work.” What would you advise history students today? “When I studied in the history department, Dean Godfrey was and still is considered one of the legendary professors. He taught the first history course I took, and he said something I’ll always remember: ‘We here at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill believe in the spirit of the humanities; and of the humanities, history has no peer.’ I shared that quote many times with one of my former partners, Nicholas Katzenbach, who was a fellow ‘old school type.’ “History grounds you in what you are, what you can become and what you have been. I would advise students to study, learn and not be embarrassed by your history. If you don’t know where you’ve been, you have no idea where you’re going, and that’s history in a nutshell. My fondest desire if I could do it all over again would be to teach history. Like Professor Ryan, I now have a library in my home in upstate New York that has over 2,000 books. Like Professor Ryan, I’ll never be able to read them all but I just like having them there.” — Erin Kelley ’13 UNC History Ph.D. appointed National Security Adviser

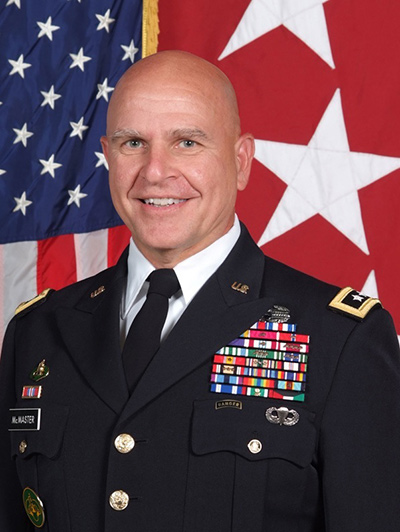

McMaster was well-known and respected in the military before his enrollment at UNC. In 1991, he played a crucial role in the Battle of 73 Easting, for which he would later be awarded a Silver Star. Col. David Fautua, a classmate of McMaster who also received his doctorate at UNC, praised McMaster’s humility while in graduate school. “We didn’t know it then that he was the best of us,” Fautua said. “Eventually we would all know what he did in the war, but he never spoke of it, so we didn’t realize that it was a big deal…. but in the midst of our cohort, we had someone who was a true hero.” In 1992, McMaster joined the inaugural cohort of UNC and Duke’s Joint Program in Military History, which began under the guidance of core faculty members Richard Kohn (UNC), Alex Roland (Duke), and Tami Biddle (Duke). Then and now, military officers who enroll in the program complete coursework, an M.A. thesis, and comprehensive exams in two years, before spending three to four years teaching and writing a Ph.D. dissertation at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. Since the establishment of the UNC-Duke Program in Military History a quarter century ago, dozens of military officers and civilians have received their doctorates. According to his classmates, McMaster was a prolific and methodical graduate student who completed his studies more quickly than his peers. Professor Wayne Lee, also a member of McMaster’s cohort and the current chair of UNC’s Curriculum in Peace, War, and Defense, described McMaster as an “unforgettable classmate” with an exceptional work ethic. In one research seminar, “You would give your assigned classmate a 30-page chapter and then they would have to read and revise it and, in our case, we also had to chase their footnotes and adjudicate how well they had used their sources,” Lee said. “H.R. handed his assigned peer a 220-page paper…This was 200 pages of him racing ahead and writing the dissertation. He was even speedier than most.” Another classmate, Robert G. Angevine, who also earned his Ph.D. in History from UNC, similarly described McMaster as “the most well prepared and organized graduate student I have ever met.” McMaster published his dissertation in 1997 as Dereliction of Duty: Lyndon Johnson, Robert McNamara, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Lies that Led to Vietnam (Harper Collins). In this book, McMaster argues that the United States lost the Vietnam War because of the actions of individuals in Washington, D.C., especially Johnson and the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who deceived the public, fell victim to petty in-fighting, and became bogged down in bureaucratic decision-making. Fautua and Lee say that the book “made a splash” in the Department of Defense, the Army, and the Clinton administration. Members of the military praised the book, Lee explained, because of McMaster’s critique of military officials who were “political animals” afraid to “stand up to the president.” Since the publication of Dereliction of Duty, Fautua believes, McMaster has “lived up to the very book he wrote.” In 2005, for example, McMaster cancelled a major training event in the Mojave Desert because of its focus on “traditional kinetic” tactics, which emphasize the use of lethal force. Instead, he created a training village to teach his regiment how to fight a war “in and amongst the people” in Iraq. “This was a completely different, novel kind of training,” Fautua said, “and it showed not only his insight into the war but the courage to swim against the current.” In interviews since his service in Iraq, McMaster has presented knowledge of history as a key to military success. In a 2007 interview with Frontline, he insisted that “one of the responsibilities of professional officers is to…prepare yourself and your organization through the study of history, because it’s very difficult before a war to understand completely the demands of that war.” Indeed, Fautua attributes an important element of McMaster’s military success to his time in the UNC-Duke military history program, insisting that “the learning we all received, the kinds of questions we were taught to ask, and that higher order of scholarship, has served him well—it has served all of us well.” –Garrett Wright |

| History in Our World |

ViewBoris Ruge: From UNC to the German Embassy

“Of course, studying history is a very good preparation to be a diplomat,” Ruge explained. “It teaches you political analysis, and that’s a big part of what historians do, even people who don’t think of themselves so much as political historians. I think it’s always political in one way or another, what you do as an historian, in terms of the subject matter.” Ruge received a Fulbright Scholarship and enrolled at UNC in 1985. Although still unsure if he wanted to pursue a career in foreign service, Ruge was already interested in political analysis. Under the direction of Gerhard Weinberg, now Professor Emeritus, Ruge examined the United States’ role in the initial phase of European integration after World War II. It was in part because of Weinberg, whom Ruge described as “a wonderful person, and a great adviser,” that Ruge gained so much from his two years at UNC. “I would say that in terms of my university-level education, Chapel Hill was definitely the most important experience that I had.” Training in history is not uncommon for German foreign service members, and Ruge works with a number of other historians, including the current German ambassador to the United States. Historians, Ruge believes, are particularly qualified to assess sources of information, write, and debate, skills of great importance to any nation’s foreign service. “This is the internet age.… We’re confronted with an overload of information, and so for anyone interested in political analysis, sorting through information and assessing it, weighing it, distilling what is actually significant and relevant, I think that’s key,” Ruge said. “And I think historians are trained to do that—certainly at UNC’s History Department.” Foreign service members must also understand how a nation’s past shapes its present circumstances. “What is important is maybe not so much sometimes what actually happened, as what people remember, or imagine, happened.” Ruge explained. “That’s crucial, the way people imagine their national history, their past. That creates the frame of reference in which you have a debate, including in this country, on all sorts of issues.” Ruge’s historical training proved particularly helpful in his previous position as the German Ambassador to Saudi Arabia and the Special Envoy to the Organization of Islamic Cooperation. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, founded in the 1930s, is a fairly new country. This shapes its current political circumstances and debates. “If you look at this country and analyze the politics, social developments, and so on, you have to take into account that it is a very young country and that, if we go back to the 1930s, it was a preindustrial, very traditional country. And one that was, by the way, never colonized, if you disregard fairly small territories on the Red Sea and on the Gulf,” Ruge said. “Those are some of the key historical features that, I think, impact on the makeup of the country today. And I think when we engage with Saudi Arabia, there are many, many considerations, but one of them would be human rights and women’s rights in particular,” Ruge explained. “For all the disagreements that we had with the government of Saudi Arabia on the issue of human rights, what I appreciated as an ambassador was that I was able to engage with many people who were advocating on behalf of human rights, who were critics of the government. I was able to meet with them, to engage with them, and in some cases have them come to the embassy. I think that is not something that is typical of the region.” Although Ruge only took the position as Minister and Deputy Chief of Mission for the German Embassy in Washington, D.C. in August 2016, he has already begun to travel the United States to participate in public engagements on behalf of the ambassador. He returned to UNC in November and again in March 2017, when he spoke about the continued partnership of the European Union and the United States. — Aubrey Lauersdorf |

| Out of the Archives |

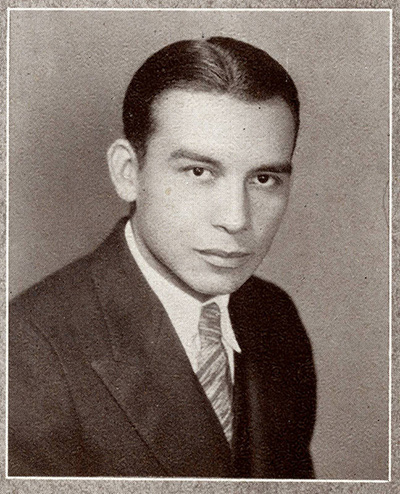

ViewA Japanese Student at UNC During World War IKevin Cherry received his MA in History at UNC in 1993, before going on to earn a Ph.D. in Library Science at UNC. He is now deputy secretary of the N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources and director of the Office of Archives, History and Parks. Cherry read the article in the Fall 2016 newsletter on Howard K. Beale and the Japanese-American student Shizuku Hiyashi that Beale helped bring to Carolina. Cherry wrote to tell us about a student from Japan at UNC, Kameichi Kato, one of perhaps twenty Japanese students at UNC, c. 1910-1922, according to Professor Heidi Kim of the Department of English and Comparative Literature at UNC. Cherry told us that Kato was a friend of Thomas Wolfe and worked for a number of Japanese firms in the United States before returning to Japan. While at Carolina, Kato wrote a long, very interesting essay on Japan and China for the North Carolina Magazine in 1917. Our thanks to Kevin Cherry for revealing to us this interesting figure from UNC history. Henry Owl: Cherokee Historian & Carolina’s First Native American Student

Owl, a member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, was the grandson of a Cherokee man who managed to escape the Trail of Tears and return home. Owl was born to a Cherokee father and a Catawba mother in western North Carolina. Since childhood, Owl displayed artistic, athletic, and academic talents. In 1921, a local newspaper described Owl as having “a commanding but pleasing appearance, a brilliant personality, and possess[ing] a profound knowledge and understanding of the customs, requirements, and nature of the Indian tribe, as well as human nature generally.” As a young man, Owl played music professionally as part of a quartet, and he also earned money as a football and baseball player. The school on the Cherokee reservation where Owl lived only went through the eighth grade, and Owl used the money he earned to continue his education. He studied carpentry at the Hampton Institute in Virginia, which had been founded during Reconstruction to educate formerly enslaved Black men. After leaving the Hampton Institute, Owl served in the U.S. Army, worked as a disciplinarian at the Cherokee reservation school, and taught manual training and agriculture at Bacone College, a school for Native students in Oklahoma. In his late twenties, Owl returned to school, receiving a bachelor’s degree from Lenoir-Rhyne College in North Carolina, where he was voted “most popular boy” in his class and was also “a dashing football player,” as a Daily Tar Heel article later described him. At Lenoir-Rhyne, Owl won an oratory contest for a presentation titled “The Challenge to the American Indian,” which drew on the history of his own nation. According to the campus newspaper, Owl “showed to his audience how the Indians, the only true Americans, a very kind and courteous people, were forced from their lands and cheated out of property. Then he gave illustration of how his own people, the Cherokees of North Carolina, have been mistreated. In conclusion, he pictured to the people the great discouraging and horrible challenge that is now facing the American Indian.” Owl pursued his interest in Cherokee history by enrolling in the graduate program in UNC’s Department of History. His 1929 master’s thesis, “The Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indians Before and After the Removal,” examined the historical and contemporary challenges faced by Cherokee people in North Carolina. In his thesis, Owl argued that: “No people have ever struggled more patiently and silently than the Cherokees have since the removal to prove their worth as a people and as real Americans. … But in the face of it all they have been disfranchised on a number of occasions. … That is the treatment that has been accorded these people that love their country as dearly as any other people ever loved a country. The future, however, holds a different story, a brighter story; for the Eastern Band of Cherokees are determined to strive even harder than in the past to prove their worth as real one hundred per cent American citizens.” A year later, Owl challenged the disenfranchisement of Cherokee people when he attempted to register to vote in Swain County in North Carolina. The registrar did not permit him to register, claiming that Owl was illiterate because he was a Cherokee person. In response, Owl returned to the registrar’s office with his master’s thesis. The registrar denied Owl a second time, now arguing that Cherokee people could not vote because they were not citizens, but wards of the federal government. However, a 1924 federal law had granted citizenship to Native American people. In 1930, Owl took his case to the federal government, testifying in front of the U.S. Senate about his experience with the Swain County registrar. In part because of Owl’s testimony, Congress confirmed the citizenship of members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, stating that they had a right to vote if they met other voting requirements in North Carolina, such as literacy tests. In practice, however, registrars in North Carolina continued to deny all Cherokee people the right to vote until after World War II. Owl went on to face discrimination after he left North Carolina. He exchanged his job with the Bureau of Indian Affairs as a teacher at reservation schools for a position in the Veteran’s Administration in Seattle. He began using his wife’s last name, Harris, in an effort to protect himself and his family from the racism they faced outside of reservations. Later in his life, Owl worked for Boeing, and he remained in Seattle until his death in 1980. Like her father, Owl’s daughter, Gladys Cardiff (Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians), is also a scholar and a teacher. Cardiff is an associate professor of English at Oakland University in Rochester, Michigan and has published numerous collections of poetry that explore her identity as a Native woman. –Aubrey Lauersdorf |

| Graduate Student News |

|

View

No items found

|

| Undergrad News |

|

View

No items found

|

Gifts to the History Department

The History Department is a lively center for historical education and research. Although we are deeply committed to our mission as a public institution, our “margin of excellence” depends on generous private donations. At the present time, the department is particularly eager to improve the funding and fellowships for graduate students.

Your donations are used to send graduate students to professional conferences, support innovative student research, bring visiting speakers to campus, and expand other activities that enhance the department’s intellectual community.

|

To make a secure gift online, please click “Give Now” above.

The Department also receives tax-deductible donations through the Arts and Sciences Foundation at UNC-Chapel Hill. Please note in the “memo” section of your check that your gift is intended for the History Department. Donations should be sent to the following address:

UNC-Arts & Sciences Foundation

Buchan House

523 E. Franklin Street

Chapel Hill, NC 27514

Attention: Ronda Manuel

For more information about creating scholarships, fellowships, and professorships in the Department through a gift, pledge, or planned gift please contact Ronda Manuel, Associate Director of Development at the Arts and Sciences Foundation: ronda.manuel@unc.edu or (919) 962-7266.

My time in the Carolina history department has given me a wide range of opportunities but, most importantly, it has shown me how to uncover narratives not otherwise told. Because our department is so diverse and rich, I have been able to learn about women fighting for Algerian independence, American Indian children forced into boarding schools, and slaves stolen from their homes in West Africa. Learning how to connect and understand narratives completely different than my own experiences has allowed me to engage with all sorts of people outside the classroom. Through my training in history, I learned not only the importance of research and writing, but also the ways to connect with and build on difference.

My time in the Carolina history department has given me a wide range of opportunities but, most importantly, it has shown me how to uncover narratives not otherwise told. Because our department is so diverse and rich, I have been able to learn about women fighting for Algerian independence, American Indian children forced into boarding schools, and slaves stolen from their homes in West Africa. Learning how to connect and understand narratives completely different than my own experiences has allowed me to engage with all sorts of people outside the classroom. Through my training in history, I learned not only the importance of research and writing, but also the ways to connect with and build on difference.

“I have been surprised at how much history has contributed to my success in biostatistics (statistics for medical research). Good communication skills, an ability to situate math in context, and an awareness of real-world problems are crucial to good biostatistics. My history major has strengthened all of these skills. In addition, closet historians seem to be everywhere in the biostatistics world. While interviewing for an internship at the National Cancer Institute, my prospective mentor confided that he had always wanted to be a history major, and that when he saw it on my application, he was immediately intrigued. When I walked into an interview for Harvard’s biostatistics PhD program, my interviewer leapt from his seat, declared, “You’re the history major!” and proceeded to pull four medical pamphlets from the 1800s from his bookshelves. We spent most of my interview examining the pamphlets, and then discussing my history thesis. I was a bit concerned that we didn’t talk about biostatistics at all, but I had a wonderful time, and it seems to have been for the best—I got in.”

“I have been surprised at how much history has contributed to my success in biostatistics (statistics for medical research). Good communication skills, an ability to situate math in context, and an awareness of real-world problems are crucial to good biostatistics. My history major has strengthened all of these skills. In addition, closet historians seem to be everywhere in the biostatistics world. While interviewing for an internship at the National Cancer Institute, my prospective mentor confided that he had always wanted to be a history major, and that when he saw it on my application, he was immediately intrigued. When I walked into an interview for Harvard’s biostatistics PhD program, my interviewer leapt from his seat, declared, “You’re the history major!” and proceeded to pull four medical pamphlets from the 1800s from his bookshelves. We spent most of my interview examining the pamphlets, and then discussing my history thesis. I was a bit concerned that we didn’t talk about biostatistics at all, but I had a wonderful time, and it seems to have been for the best—I got in.”

“What originally drew me to the history department was the excellent quality of teaching that I encountered on a consistent basis. My professors were reticent when it came to expressing their personal opinions, instead opting to pose questions that instigated some of the most thought-provoking discussions I’ve experienced at university. This afforded me the opportunity to learn how to think skeptically and critically not only about history, but also my other major, economics.”

“What originally drew me to the history department was the excellent quality of teaching that I encountered on a consistent basis. My professors were reticent when it came to expressing their personal opinions, instead opting to pose questions that instigated some of the most thought-provoking discussions I’ve experienced at university. This afforded me the opportunity to learn how to think skeptically and critically not only about history, but also my other major, economics.”

“As someone who is pursuing a career in medicine after graduation, I am frequently asked “Why history?” It is a valid question. Distant relatives and family friends find it difficult to conceive of a world where history could possibly prepare someone for a medical career. However, the history major developed in me the ability to think critically and write and speak persuasively, to intelligently engage ideas and conduct research. It also afforded me the opportunity to study abroad and travel in Europe meeting people from all over the world. These are unique skills and experiences that are not only valuable beyond the scope of a classroom, but will also translate directly into a medical career.”

“As someone who is pursuing a career in medicine after graduation, I am frequently asked “Why history?” It is a valid question. Distant relatives and family friends find it difficult to conceive of a world where history could possibly prepare someone for a medical career. However, the history major developed in me the ability to think critically and write and speak persuasively, to intelligently engage ideas and conduct research. It also afforded me the opportunity to study abroad and travel in Europe meeting people from all over the world. These are unique skills and experiences that are not only valuable beyond the scope of a classroom, but will also translate directly into a medical career.”

“My time as in the major has been defined by research. The UNC History Department not only afforded me endless opportunities to conduct original and creative research in the topics that interest me, but also the support of world-class professors and staff. I defended my senior honors thesis in March–the product of more than two year’s worth of investigation into the history of reproductive healthcare access in the Deep South. My major allowed me to experience fully the academic research, writing, and editing process: all skills I will carry with me into my future studies. I am currently applying for positions in editing and research, with an emphasis on the histories of marginalized identities.”

“My time as in the major has been defined by research. The UNC History Department not only afforded me endless opportunities to conduct original and creative research in the topics that interest me, but also the support of world-class professors and staff. I defended my senior honors thesis in March–the product of more than two year’s worth of investigation into the history of reproductive healthcare access in the Deep South. My major allowed me to experience fully the academic research, writing, and editing process: all skills I will carry with me into my future studies. I am currently applying for positions in editing and research, with an emphasis on the histories of marginalized identities.”

This year the University is rolling out a new “Quality Enhancement Plan” called “Creating Scientists: Learning by Connecting, Doing, and Making.” But it is not only in the sciences that UNC students learn through experience, conduct research, and create their own analyses. These are key elements of the practice of history and the education students receive in UNC history courses.

This year the University is rolling out a new “Quality Enhancement Plan” called “Creating Scientists: Learning by Connecting, Doing, and Making.” But it is not only in the sciences that UNC students learn through experience, conduct research, and create their own analyses. These are key elements of the practice of history and the education students receive in UNC history courses.