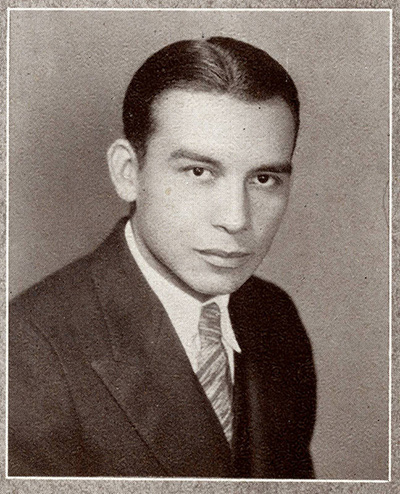

In 1929, Henry M. Owl received a master’s degree from the Department of History. Owl is one of many distinguished graduates of the program, but he is particularly important to department and campus history: Owl was the first student who publicly identified as Native American to receive a degree from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. After completing his studies, Owl used his master’s thesis to challenge the disenfranchisement of Cherokee people in North Carolina.

In 1929, Henry M. Owl received a master’s degree from the Department of History. Owl is one of many distinguished graduates of the program, but he is particularly important to department and campus history: Owl was the first student who publicly identified as Native American to receive a degree from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. After completing his studies, Owl used his master’s thesis to challenge the disenfranchisement of Cherokee people in North Carolina.

Owl, a member of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, was the grandson of a Cherokee man who managed to escape the Trail of Tears and return home. Owl was born to a Cherokee father and a Catawba mother in western North Carolina. Since childhood, Owl displayed artistic, athletic, and academic talents. In 1921, a local newspaper described Owl as having “a commanding but pleasing appearance, a brilliant personality, and possess[ing] a profound knowledge and understanding of the customs, requirements, and nature of the Indian tribe, as well as human nature generally.”

As a young man, Owl played music professionally as part of a quartet, and he also earned money as a football and baseball player. The school on the Cherokee reservation where Owl lived only went through the eighth grade, and Owl used the money he earned to continue his education. He studied carpentry at the Hampton Institute in Virginia, which had been founded during Reconstruction to educate formerly enslaved Black men.

After leaving the Hampton Institute, Owl served in the U.S. Army, worked as a disciplinarian at the Cherokee reservation school, and taught manual training and agriculture at Bacone College, a school for Native students in Oklahoma. In his late twenties, Owl returned to school, receiving a bachelor’s degree from Lenoir-Rhyne College in North Carolina, where he was voted “most popular boy” in his class and was also “a dashing football player,” as a Daily Tar Heel article later described him.

At Lenoir-Rhyne, Owl won an oratory contest for a presentation titled “The Challenge to the American Indian,” which drew on the history of his own nation. According to the campus newspaper, Owl “showed to his audience how the Indians, the only true Americans, a very kind and courteous people, were forced from their lands and cheated out of property. Then he gave illustration of how his own people, the Cherokees of North Carolina, have been mistreated. In conclusion, he pictured to the people the great discouraging and horrible challenge that is now facing the American Indian.”

Owl pursued his interest in Cherokee history by enrolling in the graduate program in UNC’s Department of History. His 1929 master’s thesis, “The Eastern Band of the Cherokee Indians Before and After the Removal,” examined the historical and contemporary challenges faced by Cherokee people in North Carolina.

In his thesis, Owl argued that: “No people have ever struggled more patiently and silently than the Cherokees have since the removal to prove their worth as a people and as real Americans. … But in the face of it all they have been disfranchised on a number of occasions. … That is the treatment that has been accorded these people that love their country as dearly as any other people ever loved a country. The future, however, holds a different story, a brighter story; for the Eastern Band of Cherokees are determined to strive even harder than in the past to prove their worth as real one hundred per cent American citizens.”

A year later, Owl challenged the disenfranchisement of Cherokee people when he attempted to register to vote in Swain County in North Carolina. The registrar did not permit him to register, claiming that Owl was illiterate because he was a Cherokee person. In response, Owl returned to the registrar’s office with his master’s thesis. The registrar denied Owl a second time, now arguing that Cherokee people could not vote because they were not citizens, but wards of the federal government. However, a 1924 federal law had granted citizenship to Native American people.

In 1930, Owl took his case to the federal government, testifying in front of the U.S. Senate about his experience with the Swain County registrar. In part because of Owl’s testimony, Congress confirmed the citizenship of members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, stating that they had a right to vote if they met other voting requirements in North Carolina, such as literacy tests. In practice, however, registrars in North Carolina continued to deny all Cherokee people the right to vote until after World War II.

Owl went on to face discrimination after he left North Carolina. He exchanged his job with the Bureau of Indian Affairs as a teacher at reservation schools for a position in the Veteran’s Administration in Seattle. He began using his wife’s last name, Harris, in an effort to protect himself and his family from the racism they faced outside of reservations. Later in his life, Owl worked for Boeing, and he remained in Seattle until his death in 1980.

Like her father, Owl’s daughter, Gladys Cardiff (Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians), is also a scholar and a teacher. Cardiff is an associate professor of English at Oakland University in Rochester, Michigan and has published numerous collections of poetry that explore her identity as a Native woman.

–Aubrey Lauersdorf