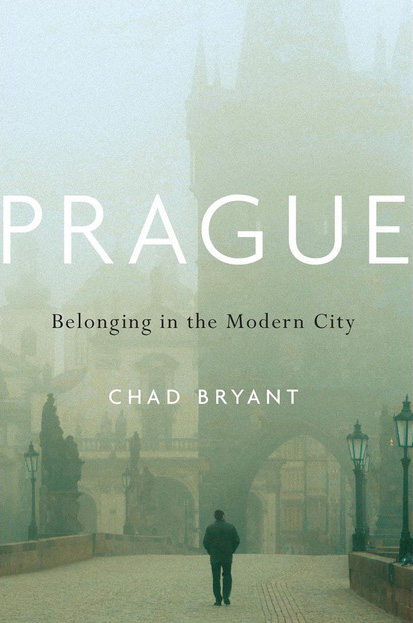

This spring, Professor Chad Bryant published his second book with Harvard University Press. Prague: Belonging in the Modern City has received favorable reviews in The Economist and the Times Literary Supplement, bringing his work to a broader public. As Bryant explained in an interview this fall, he wrote this book for both experts and interested laypeople — particularly those planning a trip to Prague, a city that has become an essential stop on any tourist’s Central European itinerary. Its architecture looks familiar enough to a foreign visitor, while its history and culture are unfamiliar enough for these visitors to attach whatever symbolic meanings they like to its buildings and landscape. At the same time, however, Prague has served as the symbolic center of the nation since the birth of the Czech nationalist movement. Successive political movements and ruling regimes have legitimated and consolidated their power by transforming the city’s physical and symbolic landscape. Unlike most other European capitals, where wartime destruction and postwar reconstruction have partially obscured this history, tourists in Prague can encounter the architectural legacies of multiple ideological projects on a short walk. Their guide books are likely to interpret this landscape for them by means of a national story — the story of a nation with a glorious past that fell into decline under foreign rule, resurrected its culture and renewed its independence, but was abandoned to Nazi occupation and then shut up behind the Iron Curtain, only to liberate itself again and reclaim its rightful place in a free Europe.

This spring, Professor Chad Bryant published his second book with Harvard University Press. Prague: Belonging in the Modern City has received favorable reviews in The Economist and the Times Literary Supplement, bringing his work to a broader public. As Bryant explained in an interview this fall, he wrote this book for both experts and interested laypeople — particularly those planning a trip to Prague, a city that has become an essential stop on any tourist’s Central European itinerary. Its architecture looks familiar enough to a foreign visitor, while its history and culture are unfamiliar enough for these visitors to attach whatever symbolic meanings they like to its buildings and landscape. At the same time, however, Prague has served as the symbolic center of the nation since the birth of the Czech nationalist movement. Successive political movements and ruling regimes have legitimated and consolidated their power by transforming the city’s physical and symbolic landscape. Unlike most other European capitals, where wartime destruction and postwar reconstruction have partially obscured this history, tourists in Prague can encounter the architectural legacies of multiple ideological projects on a short walk. Their guide books are likely to interpret this landscape for them by means of a national story — the story of a nation with a glorious past that fell into decline under foreign rule, resurrected its culture and renewed its independence, but was abandoned to Nazi occupation and then shut up behind the Iron Curtain, only to liberate itself again and reclaim its rightful place in a free Europe.

In Prague, Bryant writes the history of the city from the perspectives of five different individuals at the margins of this national story. The first, “German City,” uses the letters and published work of Karel Vladislav Zap, the writer of Prague’s first Czech-language guidebook, to reveal how middle-class Czech speakers claimed urban space for themselves in the mid-nineteenth century. Zap, an inveterate social climber, rose from obscurity to play a key role in the popularization of the Czech nationalist movement. “Czech City” turns to those Praguers excluded by the middle-class nationalist establishment — like Ferda de Podol, the flea circus manager, or Antoušek, heir to a dynasty of dog catchers — as described in Egon Erwin Kisch’s literary vignettes. Kisch, a German-speaking, Jewish-born journalist, wrote himself into a new vision of Prague as a raucous, bohemian urban landscape full of colorful characters. In “Revolution City,” the diaries of the curmudgeonly carpenter Vojtěch Berger show how left-wing organizers used parades, athletic associations, and protests to establish a social infrastructure that could be effectively mobilized for political purposes. Berger’s meticulous chronicle of his revolutionary life did not hide his disappointment in the transformation of these working-class Communist networks into the official institutions of a ruling party.

For the final two chapters of his book, Bryant was able to draw on personal interviews conducted with his subjects in addition to their written work. In “Communist City,” he examines how Hana Frejková, an actress whose father was a leading Party economist executed in the infamous Slánský trial, succeeded in both fashioning an independent identity and expressing herself artistically despite facing both political repression and social exclusion. Her memoir describes the journey of a loner — a solitér, as she continually described herself in interviews — who finds acceptance and fulfillment through art and through her family. Finally, “Global City” discusses the experiences of Duong Nguyen, whose parents were among the many Vietnamese students and workers who moved to the Czech Republic under state socialism and stayed on after 1989. Her thoughtful and forthright blog about living between two cultures presented a distinct perspective ignored by the broader Czech public as well as the traditional leadership of the Vietnamese community. It offered a picture of Prague as a cosmopolitan city despite itself, whose diversity and pluralism was too frequently overlooked or denied.

For the final two chapters of his book, Bryant was able to draw on personal interviews conducted with his subjects in addition to their written work. In “Communist City,” he examines how Hana Frejková, an actress whose father was a leading Party economist executed in the infamous Slánský trial, succeeded in both fashioning an independent identity and expressing herself artistically despite facing both political repression and social exclusion. Her memoir describes the journey of a loner — a solitér, as she continually described herself in interviews — who finds acceptance and fulfillment through art and through her family. Finally, “Global City” discusses the experiences of Duong Nguyen, whose parents were among the many Vietnamese students and workers who moved to the Czech Republic under state socialism and stayed on after 1989. Her thoughtful and forthright blog about living between two cultures presented a distinct perspective ignored by the broader Czech public as well as the traditional leadership of the Vietnamese community. It offered a picture of Prague as a cosmopolitan city despite itself, whose diversity and pluralism was too frequently overlooked or denied.

Despite their obvious differences, all five characters occupied the city’s social margins. All five shared a modern motivation to fashion their own identities and find a way to belong in their city. And all did so through writing. One of the greatest challenges of this project, Bryant noted, was finding a way to incorporate each individual narrative into his broader historical argument without distorting or dismantling each author’s interpretation of their own experience. Berger’s diaries were a consciously crafted document of the worker’s movement that made little reference to his family or private life. Frejková initially resisted the idea that her memoir could illustrate themes of belonging, and insisted that her story was a purely individual one.

The scope of the book posed another difficulty. Bryant sought both to create a narrative that would keep the attention of travelers or other interested readers, but also to address a broad set of historical questions and engage a different group of specialists with each chapter. In Frejková’s chapter, for instance, Bryant does not only recount the story of a successful actress and victim of state persecution. He also discusses the transformation of the Czechoslovak economy after the Second World War; the development of Prague’s outlying residential districts; popular culture and entertainment during the final years of state socialism; and both the human rights declaration Charter 77 and the official response, the “Anticharter.” Each chapter draws on a wide secondary literature in Czech, English, and German. In keeping with the inclusive themes of his book, Bryant strove to bring the work of Czech scholars to an English-speaking readership.

Bryant emphasized in an interview that Praguers continue to make creative use of their symbolically resonant urban spaces. He spoke admiringly about the memorial to Czech victims of Covid-19 in March 2021 organized by the civic organization Milion chvílek za demokracii (A Million Moments for Democracy). Despite the high quality of its health care system, the Czech Republic has one of the highest Covid-19 death rates in the European Union. The 25,000 crosses painted on the cobblestones of Prague’s famous Old Town Square used both powerful cultural symbols and the eerie desertion of public space under lockdown to make the Czech government’s failure to protect its citizens starkly clear.

But Prague’s cultural and symbolic dominance likely contributes to another form of exclusion that has proven deadly during the pandemic. In the Czech Republic, the virus has taken its greatest toll in the Karlovy Vary region, a peripheral part of western Bohemia that has long suffered from systemic economic and social problems — and whose complex history also does not fit neatly into the dominant national narrative. As hospitals in the area were overrun with seriously ill patients and local political leaders protested that the central government was not distributing the vaccine effectively, the prime minister dismissed their concerns: “It’s always something from the Karlovy Vary region. It’s the absolute worst region, historically, in everything.”

As Bryant explained, however, his work seeks not only to tell a different story about Prague, but also to explore ways of understanding history that are more open, inclusive, and dynamic. By presenting the history of one city through the lives of those excluded from the narratives that have shaped its symbolic landscape, he encourages readers to imagine a different future.

-Mira Markham