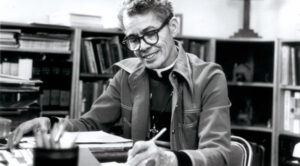

Anna Pauline “Pauli” Murray (1910-1985) was one of the most remarkable intellectuals and human rights advocates of the 20th Century. She also had strong personal ties to North Carolina, to UNC, and to the intellectual work carried out in this building. These reasons support the proposal to rename our building in Pauli Murray’s honor.

Anna Pauline “Pauli” Murray (1910-1985) was one of the most remarkable intellectuals and human rights advocates of the 20th Century. She also had strong personal ties to North Carolina, to UNC, and to the intellectual work carried out in this building. These reasons support the proposal to rename our building in Pauli Murray’s honor.

Pauli Murray’s work as an activist, women’s rights advocate, and lawyer is reflected in her scholarship, as her poems, articles, and books critique the anti-Blackness of the US legal system and call for greater gender equality in the Civil Rights Movement. Though Murray began publishing in New York City, her work already reflected the difficulties she had experienced in her youth. Murray was born on November 10, 1910 in Baltimore, Maryland, but after her parents’ early deaths moved to Durham, North Carolina to live with her maternal grandparents. In Durham, Murray was exposed to the oppression of white supremacy which influenced her later works.

At sixteen, Murray moved to New York City to attend Hunter College, where she received a degree in English literature. While at Hunter College, Murray wrote an article on the struggle of her maternal grandmother against racism in North Carolina, a piece that became the foundation for her 1956 book, Proud Shoes, a biography of her grandmother’s experience with anti-Blackness in Durham. Additionally, she began to publish articles and poems in Common Sense, a left-wing monthly journal, and The Crisis, a publication of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). After graduating from Hunter College in 1933, Murray spent eight years engrossing herself in civil rights activism, where she was inspired to pursue a career in social justice legislation. Her application was rejected by the all-white University of North Carolina in 1938, and she instead enrolled in Howard University Law in 1941, where she continued publishing her work, including her prominent essay “Negros are Fed Up” and magisterial poem “Dark Testament.”

After graduating, Murray moved back to New York City and began working for and publishing on the Civil Rights Movement in earnest. Murray’s work focused on the intersection of legislation, race, and gender, and her 1951 book States’ Laws on Race and Color was declared the “Bible” of civil rights legislation by Thurgood Marshall, the head of the NAACP’s legal department. Murray continued to integrate gender into her critiques of race legislation, as she coined the term “Jane Crow” in a 1964 speech highlighting the gendered effect of Jim Crow legislation on African American women. She developed this idea further in her pivotal 1965 article “Jane Crow and the Law: Sexual Discrimination and Title VII.”

Murray’s critiques of sexism did not end with the American legislative system, however, as she was one of the first individuals to criticize sexism within the civil rights movement itself. In her speech “The Negro Woman in the Quest for Equality” she wrote: “I have been increasingly perturbed over the blatant disparity between the major role which Negro women have played and are playing in the crucial grassroots level of our struggle and the minor role of leadership they have been assigned.” She continued promoting this platform in her 1964 legal memorandum to add “sex” as a protected category in the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Though Murray’s publishing largely ended when she joined a seminary and became an Episcopal priest in 1977, her activism advanced racial and gender equality in both legislation and the civil rights movement. Her memory resonates through the continued republishing of her works and is apparent at the University of North Carolina through widespread support for renaming Hamilton Hall to Pauli Murray Hall in her honor.

-Nicole Harry