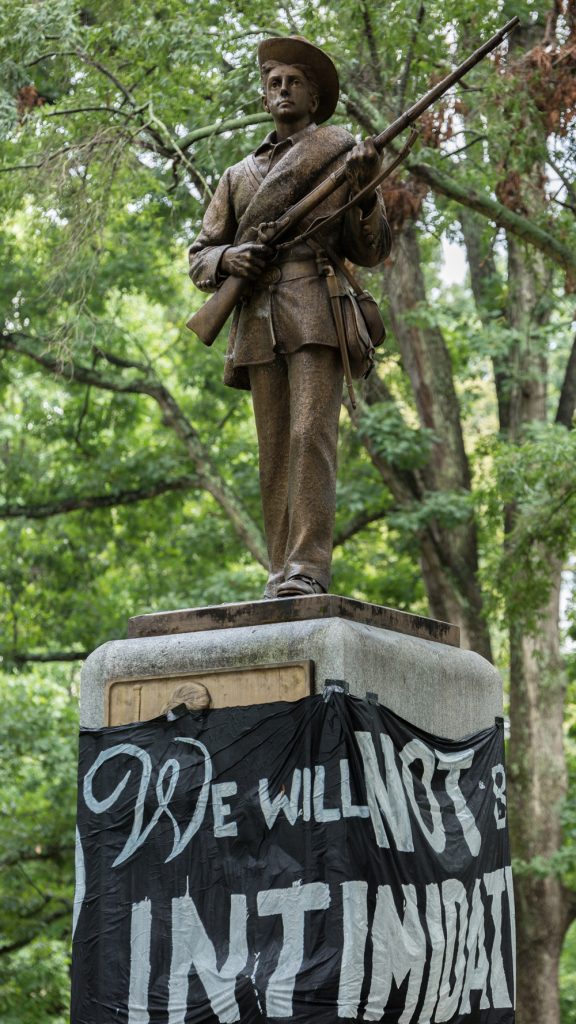

The Department of History has added its voice to growing calls to remove the Confederate Memorial from campus. In the October 4 statement, the Department urged UNC and state officials to “pursue every avenue to remove the ‘Silent Sam’ monument” from its “prominent place” on campus. The History Department joins several other departments and schools in this call for action, including Anthropology, Religious Studies, and the School of Law, as well as the Chapel Hill Chamber of Commerce.

According to William Sturkey, an assistant professor who specializes in 20th-century African American history, monuments like Silent Sam were built by “white supremacists to, in part, promote or justify the morality and political mission of white supremacy.” Such “relics” of Jim Crow “don’t work outside a Jim Crow system, where people of color are allowed to attend and work at the University of North Carolina,” he said.

Silent Sam has been controversial since the end of Jim Crow in Chapel Hill, but the most recent round of student-led protests began after the August “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, where white nationalists protested the removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee from the University of Virginia campus and one counter-protester was killed. “For me, the biggest issue with Silent Sam is that it sends a message to non-white students and campus members that they and their concerns are not fully welcome here on campus,” said Jennifer Standish, a History graduate student involved in an ongoing student protest of Silent Sam. The public response to student protests has been mixed. “There have been some really productive conversations,” she said, “but also some very hostile and violent ones as well.”

History faculty have worked hard to engage the wider community in a dialogue about the meaning of Silent Sam. In late August, William Sturkey and Harry Watson, the Atlanta Alumni Distinguished Professor of Southern Culture, participated in a Carolina Public Humanities panel moderated by Lloyd Kramer, history professor and director of Carolina Public Humanities. Watson told the audience that while the meaning of symbols shifts over time, Silent Sam still has an explicit pro-slavery meaning and “is a rallying point for those who celebrate white supremacy today.” As a community, he added, we must show our common commitment to a non-racist society. William Sturkey and Fitz Brundage, department chair and the William B. Umstead Distinguished Professor, also discussed Silent Sam in a Community Forum on the television station WCHL and Brundage also appeared on PBS Newshour to speak about Confederate memorials.

In the Raleigh News & Observer, James Leloudis, a history professor who specializes in the modern South, outlined the origins of the memorial. UNC trustees and the United Daughters of the Confederacy began planning the statue in 1908 and dedicated it during spring commencement in 1913. Those dates are important: Silent Sam was built during a politically charged period of Confederate memorialization. Before 1902, North Carolina had only six Confederate memorials; between 1902 and 1926, white North Carolinians built fifty-three. In a widely shared article in the online magazine Vox, Brundage noted that “the installation of the 1,000-plus memorials across the US” – including Silent Sam – happened while “the South was fighting to resist political rights for black citizens.”

With no public consultation, organizations like the United Daughters of the Confederacy sponsored the installation of pro-Confederate statues in prominent places. The process, Brundage argued, was one of “private groups colonizing public space” for a white supremacist agenda.

Much of their racist propaganda “was academic,” Sturkey said. “It was teaching, going into schools, going into colleges, producing scholarship, having essay writing contests” with a pro-Confederate slant. Since the 1960s, historians have corrected the historical record but the statues remain on the grounds of many civic institutions.

Part of the struggle is that “we can’t even get people to admit that that Jim Crow was even that bad because that would acknowledge that there might be some sort of historic effect that has resulted in contemporary inequalities and disadvantages for certain people,” Sturkey added. He also noted that the deadly violence of the Charlottesville rally, as well as Dylann Roof’s murder of nine African-Americans at a church in Charleston in 2015, show how these monuments are viewed by the “worst elements in our society.” “Dylann Roof celebrated the Confederacy,” Sturkey said, “and celebrated those Confederate monuments and used that to bolster his racial superiority in a way that allowed him to sit in a church and kill nine people…these things are very meaningful to a lot of people and can in fact be dangerous when interpreted the wrong way.”

Speaking and writing about the historical context of Silent Sam is, to these professors and students, consistent with the mission of UNC’s History Department. “If you work at a history department at a public university then you are a public historian,” Sturkey said. “When these issues come along I have an opportunity and a duty even to help contextualize these things for the public so that they can be better informed about what might happen with these statues or what they might actually represent.”

The Department’s statement on Silent Sam suggests that if moved “to an appropriate place,” the monument might “become a useful historical artifact with which to teach the history of the university and its still incomplete mission to be ‘the People’s University.’” At present, however, the statue continues “to promote malicious values that have persisted too long on this campus, in this state, and in this nation.” The Department website lists further resources on this subject.

Joshua Tait