When the first students enrolled in the University of North Carolina in 1795, no women were among them. In fact, the University explicitly forbid women until 1897. The following year, Sallie Walker Stockard became the first woman to receive a B.A. degree from UNC. She then completed her M.A. in 1900, writing a history of Alamance County that represented her first step toward becoming a prominent author of local histories.

In her autobiography, which is housed in the North Carolina Collection at UNC, Stockard wrote that she first gained a passion for education from her mother. “She had told me of Homer, Virgil, and Milton. I was anxious to learn to read Greek and Latin, to be my mother’s equal intellectually.”

Since her family could not afford to send her to college, Stockard earned money to further her schooling, including by sewing dresses for the young women who worked in the textile mills in Graham, North Carolina, where she grew up. “The sewing machine seldom stopped before midnight,” Stockard recalled in her autobiography. “A doctor friend who visited us said to work such long hours was unwise; it could injure my health. But I did not stop. I kept busy with the sewing to earn enough to go to college.”

In 1897, Stockard was allowed to enroll in UNC only because she had already completed a B.A. at Guilford College in Greensboro. Although Dr. Edwin A. Alderman, the president of the University, successfully convinced the Board of Trustees to admit women in 1897, the new policy only included women who had already earned a degree at another institution. In 1940, UNC changed the rule, but only for women whose families lived locally. Indeed, women students like Stockard would not receive full access to UNC until Title IX passed in 1972. (During that time, black women were fully excluded from the University; in 1951, Gwendolyn Harrison sued UNC after administrators cancelled her enrollment in a graduate program upon realizing that she was black.)

Because UNC had no dormitory for women in these early years, Stockard and other early women students were accepted on the condition that they could find housing. Upon arriving in Chapel Hill, Stockard stayed with President Alderman’s sister-in-law until she arranged more permanent accommodations, living in the home of a local family in exchange for taking care of their daughter. Not until the 1920s did the University build a dormitory for women.

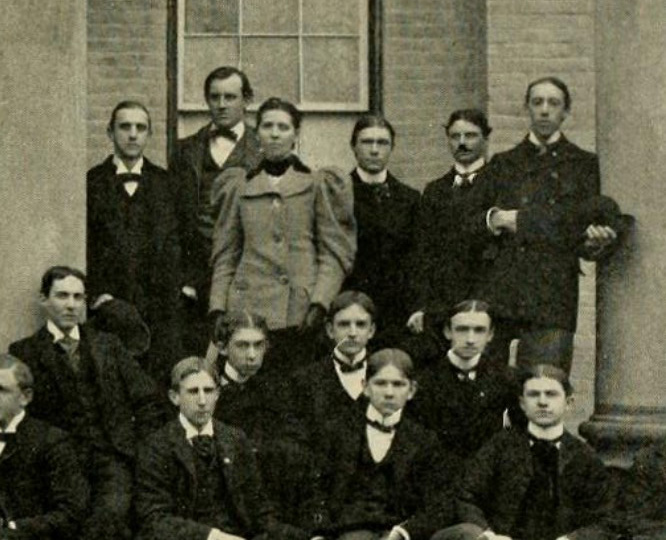

As more women began to enroll in UNC–from fewer than ten per class in the first few years to 57 in 1920 and more than 500 in 1939–administrators placed more formal limitations on women students. For example, Stockard posed with fellow graduates in her class photo in 1898, while later women students were excluded from theirs. Soon, women who enrolled in the University received a booklet of rules that applied only to female students.

Increasingly, women students also faced resistance from their male peers. Stockard’s autobiography suggests that she built positive relationships with at least some male students. In 1923, however, the Daily Tar Heel took a strong stance against co-education. Protesting the proposed dormitory for women students, the paper’s editorial board expressed fear that “the University would become overrun with girl students” and declared that “the men students at this University have no desire for them here, and never will have any desire for them here.”

After finishing her M.A. in 1900, Stockard published The History of Alamance, the first of three local histories. Two years later, she released The History of Guilford County, North Carolina. After moving to Arkansas, she published The History of Lawrence, Jackson, Independence and Stone Counties of the Third Judicial District of Arkansas in 1904. As Stockard later wrote in her autobiography, “I was something of a pioneer in the writing of local Southern history.”

To readers today, Stockard’s histories reflect an era of historical scholarship that treated white settlers as drivers of historical progress. In The History of Alamance, she confined the area’s indigenous inhabitants to stereotyped roles, and rather than engage with the local history of slavery and the Civil War, Stockard mostly avoided the topics. In her telling, the relative lack of immigration to the state by people from Eastern and Southern Europe, who by 1900 represented the majority of immigrants to the United States, meant that “the purest race on earth live in North Carolina.”

To readers today, Stockard’s histories reflect an era of historical scholarship that treated white settlers as drivers of historical progress. In The History of Alamance, she confined the area’s indigenous inhabitants to stereotyped roles, and rather than engage with the local history of slavery and the Civil War, Stockard mostly avoided the topics. In her telling, the relative lack of immigration to the state by people from Eastern and Southern Europe, who by 1900 represented the majority of immigrants to the United States, meant that “the purest race on earth live in North Carolina.”

Stockard’s other projects reflected her commitment to an interdisciplinary education. She studied psychology at Clark University in Massachusetts in 1902. In 1903, she delved into fiction-writing with The Lily of the Valleys, a dramatization of the Song of Solomon. After separating from her husband, whom she met and married in Arkansas, she took her two children to Texas and then to Oklahoma, where she was a schoolteacher. In the 1920s, when she was in her mid-40s, Stockard completed a second M.A. at Columbia University Teacher’s College in New York. She later founded a local newspaper in New York before retiring to Florida.

Stockard moved frequently, in part because she saw travel as another form of education. In her autobiography, she wrote that “I have attempted to supplement the training I have received in colleges and universities with knowledge and wisdom gained thru experience. The value of experience and travel can never be overestimated. With the passing of every mile, a new bit of knowledge is found.”

– Aubrey Lauersdorf