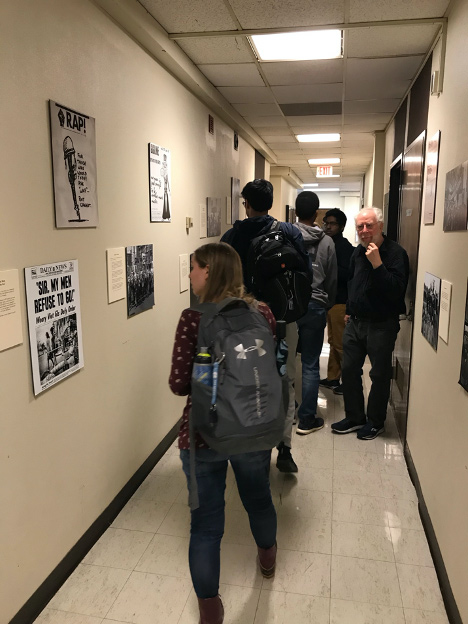

In the early weeks of the Spring 2020 semester, department students, staff, and faculty on the fifth floor of Hamilton Hall stepped into the past. Visitors were not ushered into a classroom or issued a stack of books to read. Instead, for four weeks between January 15 and February 15, the department’s corridors provided a temporary home for a traveling exhibition about anti-war protests during the Vietnam Era. The exhibit, a project connected to a 2019 book entitled Waging Peace in Vietnam: U.S. Soldiers and Veterans who Opposed the War, was edited and curated by Ron Carver, David Cortright, Barbara Doherty to commemorate the sometimes forgotten stories of U.S. soldiers who opposed the war. For those who lived through the period, the “Waging Peace in Vietnam” exhibit stirred memories of a polarizing moment when social values shifted, trust in public institutions waned, and many aspects of daily life became an exercise in negotiating opposing political camps. Today’s students, who have only second- or third-hand knowledge of the Vietnam Era, learned about unknown aspects of anti-war protests within the U.S. armed forces, particularly the networks formed through underground newspapers, posters, flyers, and photographs.

In the early weeks of the Spring 2020 semester, department students, staff, and faculty on the fifth floor of Hamilton Hall stepped into the past. Visitors were not ushered into a classroom or issued a stack of books to read. Instead, for four weeks between January 15 and February 15, the department’s corridors provided a temporary home for a traveling exhibition about anti-war protests during the Vietnam Era. The exhibit, a project connected to a 2019 book entitled Waging Peace in Vietnam: U.S. Soldiers and Veterans who Opposed the War, was edited and curated by Ron Carver, David Cortright, Barbara Doherty to commemorate the sometimes forgotten stories of U.S. soldiers who opposed the war. For those who lived through the period, the “Waging Peace in Vietnam” exhibit stirred memories of a polarizing moment when social values shifted, trust in public institutions waned, and many aspects of daily life became an exercise in negotiating opposing political camps. Today’s students, who have only second- or third-hand knowledge of the Vietnam Era, learned about unknown aspects of anti-war protests within the U.S. armed forces, particularly the networks formed through underground newspapers, posters, flyers, and photographs.

During the first week of the exhibit’s residence in the History Department, two contributors spoke about their personal experiences and the ideas that led to the project. Carver, one of the book’s editors, explained how his early engagement in the Civil Rights movement led him to work with enlisted soldiers and veterans who opposed the war in Vietnam. Having traveled the country to register voters, organize sit-ins, and give voice to the disenfranchised, Carver pivoted to a new venue: coffee houses. For nearly three years, Carver and a group of colleagues founded cafes near stateside military bases, catering to soldiers who desperately needed safe spaces to relax and discuss their grievances in towns that were often devoid of any non-military life. To better understand soldiers, the brutality of the war, and its implications for Vietnamese civilians, Carver decided he had to travel to the war zone. During multiple trips to Vietnam, he extended his social and political networks, especially in the South Vietnamese capital city of Saigon.

After the war’s end, Carver and his friend Mitchell Zimmerman felt compelled to bring the public’s attention to stories they had heard from soldiers and Vietnamese civilians about the the war’s horrors. An early result of this work was Dr. Spock Speaks Out On Vietnam, an accessible monograph authored in 1968 by Benjamin Spock, famous for his 1946 book Baby and Child Care. Carver and Zimmerman highlighted such controversial stories from the annals of the anti-war movement to draw attention to the great diversity within the anti-war movement.

Susan Schnall, a nurse and lieutenant in the U.S. Navy from 1967 to 1968, also spoke at the exhibit’s opening at Hamilton Hall. Schnall, who joined the military to ease soldiers’ return to everyday life, offered an inside view of the harsh realities that confronted U.S. troops who opposed the war. During a 1968 anti-war demonstration, Schnall wore her navy uniform in defiance of a requirement of the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ) that prevented soldiers from sporting military regalia in unapproved settings such as protests. Convicted of “behavior unbecoming of an officer,” she was sentenced to six months of confinement and hard labor. Following her discharge from the navy, Schnall worked with veterans, GIs, and civilian protestors to distribute anti-war materials throughout military bases in the United States and Vietnam. Addressing a common stereotype about Vietnam veterans, Schnall believes that soldiers coping with post-war mental and emotional distress suffered not from a pathological ailment (PTSD) but rather a “moral injury” imposed upon them by a war-hungry government and traumatic circumstances.

Though the “Waging Peace in Vietnam” exhibit has been temporarily halted by COVID-19 shutdowns, its creators plans to continue touring American university campuses, veteran halls, and libraries. As part of his commitment to the people of Vietnam, Carver also brought the installation to Ho Chi Minh City from September 2019 to March 2020. Committed to publicly-oriented research, education, and conversations, UNC Chapel Hill’s History Department anticipates hosting similar presentations in the near future.