Winter 2021 – Archives

| Expand All | Collapse All |

| Department News |

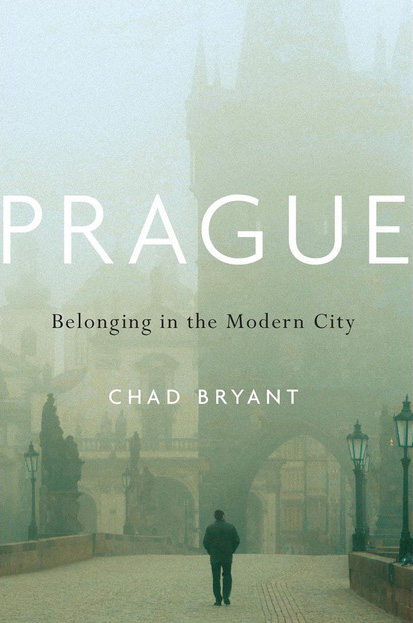

ViewProfessor Chad Bryant publishes Prague: Belonging in the Modern City

In Prague, Bryant writes the history of the city from the perspectives of five different individuals at the margins of this national story. The first, “German City,” uses the letters and published work of Karel Vladislav Zap, the writer of Prague’s first Czech-language guidebook, to reveal how middle-class Czech speakers claimed urban space for themselves in the mid-nineteenth century. Zap, an inveterate social climber, rose from obscurity to play a key role in the popularization of the Czech nationalist movement. “Czech City” turns to those Praguers excluded by the middle-class nationalist establishment — like Ferda de Podol, the flea circus manager, or Antoušek, heir to a dynasty of dog catchers — as described in Egon Erwin Kisch’s literary vignettes. Kisch, a German-speaking, Jewish-born journalist, wrote himself into a new vision of Prague as a raucous, bohemian urban landscape full of colorful characters. In “Revolution City,” the diaries of the curmudgeonly carpenter Vojtěch Berger show how left-wing organizers used parades, athletic associations, and protests to establish a social infrastructure that could be effectively mobilized for political purposes. Berger’s meticulous chronicle of his revolutionary life did not hide his disappointment in the transformation of these working-class Communist networks into the official institutions of a ruling party.

Despite their obvious differences, all five characters occupied the city’s social margins. All five shared a modern motivation to fashion their own identities and find a way to belong in their city. And all did so through writing. One of the greatest challenges of this project, Bryant noted, was finding a way to incorporate each individual narrative into his broader historical argument without distorting or dismantling each author’s interpretation of their own experience. Berger’s diaries were a consciously crafted document of the worker’s movement that made little reference to his family or private life. Frejková initially resisted the idea that her memoir could illustrate themes of belonging, and insisted that her story was a purely individual one. The scope of the book posed another difficulty. Bryant sought both to create a narrative that would keep the attention of travelers or other interested readers, but also to address a broad set of historical questions and engage a different group of specialists with each chapter. In Frejková’s chapter, for instance, Bryant does not only recount the story of a successful actress and victim of state persecution. He also discusses the transformation of the Czechoslovak economy after the Second World War; the development of Prague’s outlying residential districts; popular culture and entertainment during the final years of state socialism; and both the human rights declaration Charter 77 and the official response, the “Anticharter.” Each chapter draws on a wide secondary literature in Czech, English, and German. In keeping with the inclusive themes of his book, Bryant strove to bring the work of Czech scholars to an English-speaking readership. Bryant emphasized in an interview that Praguers continue to make creative use of their symbolically resonant urban spaces. He spoke admiringly about the memorial to Czech victims of Covid-19 in March 2021 organized by the civic organization Milion chvílek za demokracii (A Million Moments for Democracy). Despite the high quality of its health care system, the Czech Republic has one of the highest Covid-19 death rates in the European Union. The 25,000 crosses painted on the cobblestones of Prague’s famous Old Town Square used both powerful cultural symbols and the eerie desertion of public space under lockdown to make the Czech government’s failure to protect its citizens starkly clear. But Prague’s cultural and symbolic dominance likely contributes to another form of exclusion that has proven deadly during the pandemic. In the Czech Republic, the virus has taken its greatest toll in the Karlovy Vary region, a peripheral part of western Bohemia that has long suffered from systemic economic and social problems — and whose complex history also does not fit neatly into the dominant national narrative. As hospitals in the area were overrun with seriously ill patients and local political leaders protested that the central government was not distributing the vaccine effectively, the prime minister dismissed their concerns: “It’s always something from the Karlovy Vary region. It’s the absolute worst region, historically, in everything.” As Bryant explained, however, his work seeks not only to tell a different story about Prague, but also to explore ways of understanding history that are more open, inclusive, and dynamic. By presenting the history of one city through the lives of those excluded from the narratives that have shaped its symbolic landscape, he encourages readers to imagine a different future. -Mira Markham The Sallie Markham Michie Trust Legacy Continues for 2021

The Trust’s chair, Sarah Snow, outlined in an interview that “the intent [of the trust] is to challenge students to research and publish on the era of the American Revolution, the British/American colonial era, and/or the tradition of rights and liberties established by the Magna Carta.” Thus, scholarships are awarded annually from the Sallie Markham Michie Trust to select applicants whose research fulfills the goals of the Trust. Beyond her associations with the Daughters of the American Revolution and Magna Carta Dames Society, Mrs. Markham was also a longtime resident of Carrboro and Chapel Hill. Thus, she prioritized the allocation of scholarships from her trust to residents of Orange County. Despite the Revolutionary-era focus of these scholarships, past recipients from the department have applied their funds to projects on Latin America, Europe, and modern America, as well as early North America. Steven Weber, who received a scholarship in 2017, was able to apply the funding toward his project on the coverage of the American Revolution by the French press, exploring the legacy and impact of the American Revolution beyond the continent. The Sallie Markham Michie Trust scholarship allowed Steve to take his first major research trip to Paris, where he worked in the city’s diplomatic archives to develop the direction of his dissertation. Beyond the scholarship itself, he valued “the ability to present my Master’s work to a public audience at the DAR meeting,” which “was really helpful in thinking about what my main contributions were and how they could be presented to a non-academic audience as significant and interesting.”

Another past recipient, Ariel Wilks, applied her scholarship funds to research closer to the American continent. The Daughters of the American Revolution and Magna Carta Dames Society awarded Ariel a scholarship in 2019 for her dissertation project, which investigated the role of privateers in the professionalization of the American Navy, especially in the amphibious warfare of the American Revolution and War of 1812. She noted that “my project fits the DAR goals as it very much centers around developing the scholarship of early America and focuses on an area within that scholarship that is not heavily emphasized.” With the support of the Sallie Markham Michie Trust, Ariel has been able to focus on developing her research topic and comfortably plan to begin her archival research this spring. In 2021, eight graduate students applied for scholarships from the Sallie Markham Michie Trust, and the department looks forward to seeing how the recipients are able to support their own research, as well as the goals of Sallie Markham Michie, the Daughters of the American Revolution, and the Magna Carta Dames with the support gifted by the scholarships. -Nicole Harry |

| Faculty Spotlight |

|

View

No items found

|

| Alumni Spotlight |

ViewAlumnus Alex Hodges advocates for the value of historical training Hodges, who is currently Vice President & General Manager Americas for the Global Products Division of Owens & Minor, a FORTUNE 500 global healthcare logistics company, knows a thing or two about the career preparation provided by a history degree. As a member of the department’s Career Mentor Coalition (described in last Spring’s newsletter), Hodges partners with other alumni of the department to provide professional advice and mentoring to history majors and minors in the early stages of their careers. “I was not alone when I think about my colleagues in the business world. Most of them are from liberal arts backgrounds. Even the highly competitive investment banks will also value a liberal arts background. It’s my belief that I wasn’t unique.” Hodges’ advocacy for the value of historical training finds reflection in his support for the efforts of the department, and the university, to reckon with the uglier chapters of Carolina’s past. A recipient of the prestigious Morehead-Cain scholarship who came to Carolina from the North Shore of Massachusetts, Hodges got “hooked” into history while taking a course with Joel Williamson (1929-2019), a distinguished historian of the American South who taught in the department for 43 years and held the Lineberg Professorship of the Humanities. “He was such an amazing teacher, and I ultimately decided to write my senior thesis under his mentorship. Based on his class, the Wilmington Race Riot (really the massacre and coup of Wilmington of 1898) was a topic that fascinated me.” Conducting research for his thesis proved to be a formative experience. “I did not have a very disciplined academic path, but that was the topic that got me going. It was the History Department, Joel’s mentorship, and this thesis topic that ignited my studies. I spent a year in Wilson Library going through microfilm and microfiche. That became the core of my academic life and a focal point of my studies.” Journalism might have been a logical career path for Hodges after college given his family’s broad liberal arts background (though his father was in finance). In his junior year, however, he did an internship with a company in Chicago, and found the experience eye-opening. “I liked that environment, I liked working with people who have a purpose of making a product, and I started pursuing those opportunities after college.” Hodges entered a management training program at SmithKline Beecham (now Glaxo SmithKline), a company with a long history of recruiting at Carolina, that involved rotational assignments in different business areas. He acquired multidisciplinary exposure in positions that took him across the U.S., to England, and to Mexico City. In all these roles, Hodges feels strongly that historical training served him well. “Regardless of what profession you choose for your career journey, the history degree gives you the foundation of critical thinking, of the core discipline of research, the ability to solve problems by creating a hypothesis and having to prove or disprove that hypothesis through critical thinking, and ultimately communicating, both in writing and orally, that point of view in a persuasive way. Those skills are core to any profession, and you get all those skills in a history degree.” Though Hodges has enjoyed a multifaceted international career since his student days, he has always attached great importance to spreading awareness about the university’s racist past. On a visit to the campus bookstore in January 2020, right before the pandemic, Hodges picked up a copy of David Zucchino’s Pulitzer Prize winning Wilmington’s Lie: the Murderous Coup of 1898 and the Rise of White Supremacy (Grove Press, 2020) and leafed through the bibliography. “Oh my gosh!” he recalls telling himself. “My thesis was cited a couple times and David and I had a good exchange as a result of that.” The experience reinforced Hodges’ belief in the need to educate Carolina students, and the North Carolina public, about the devastating impact of White supremacy on the state’s history. “When you think about 1898, where you’re barely 40 years after the Civil War and slavery ended, that you had this vibrant community including middle class professionals in positions of political power at a local level, but also at a professional level, and a thriving community in Wilmington, NC, suddenly desecrated, you sit back and think what would life have been like, what would 2021-2022 be like, for the African American community if those events, and later Jim Crow had not happened?” Hodges has been a passionate advocate for the removal of White supremacist Josephus Daniels’ name from the official title of the Student Stores, and believes the department should regularly offer a course on racism in North Carolina at the turn of the century. He strongly supports the department’s petition to officially rename our building Pauli Murray Hall. “I was absolutely inspired by her revolutionary work in the early days of civil rights, how she influenced Thurgood Marshall and ultimately became an Episcopalian priest late in life.” The importance of these efforts to reckon with UNC’s racist past could not be more clear-cut in his view. “Let’s make sure we are not naming buildings after people whose legacy is a stain on the university and who do not need to be honored.” Hodges, whose eldest daughter graduated from Carolina last year, is passionate about the university and about our department. Last year, he and his spouse generously created the The Hodges Family Graduate Student and Faculty Excellence Fund in the Department of History to support research and teaching in African American history. In addition, through his advocacy and support for our recent alumni, he continues to play an important and active role in departmental life, and serve as a model for our majors, both as a business professional and as a historian. |

| History in Our World |

ViewPauli Murray’s Powerful Legacy

Pauli Murray’s work as an activist, women’s rights advocate, and lawyer is reflected in her scholarship, as her poems, articles, and books critique the anti-Blackness of the US legal system and call for greater gender equality in the Civil Rights Movement. Though Murray began publishing in New York City, her work already reflected the difficulties she had experienced in her youth. Murray was born on November 10, 1910 in Baltimore, Maryland, but after her parents’ early deaths moved to Durham, North Carolina to live with her maternal grandparents. In Durham, Murray was exposed to the oppression of white supremacy which influenced her later works. At sixteen, Murray moved to New York City to attend Hunter College, where she received a degree in English literature. While at Hunter College, Murray wrote an article on the struggle of her maternal grandmother against racism in North Carolina, a piece that became the foundation for her 1956 book, Proud Shoes, a biography of her grandmother’s experience with anti-Blackness in Durham. Additionally, she began to publish articles and poems in Common Sense, a left-wing monthly journal, and The Crisis, a publication of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). After graduating from Hunter College in 1933, Murray spent eight years engrossing herself in civil rights activism, where she was inspired to pursue a career in social justice legislation. Her application was rejected by the all-white University of North Carolina in 1938, and she instead enrolled in Howard University Law in 1941, where she continued publishing her work, including her prominent essay “Negros are Fed Up” and magisterial poem “Dark Testament.” After graduating, Murray moved back to New York City and began working for and publishing on the Civil Rights Movement in earnest. Murray’s work focused on the intersection of legislation, race, and gender, and her 1951 book States’ Laws on Race and Color was declared the “Bible” of civil rights legislation by Thurgood Marshall, the head of the NAACP’s legal department. Murray continued to integrate gender into her critiques of race legislation, as she coined the term “Jane Crow” in a 1964 speech highlighting the gendered effect of Jim Crow legislation on African American women. She developed this idea further in her pivotal 1965 article “Jane Crow and the Law: Sexual Discrimination and Title VII.” Murray’s critiques of sexism did not end with the American legislative system, however, as she was one of the first individuals to criticize sexism within the civil rights movement itself. In her speech “The Negro Woman in the Quest for Equality” she wrote: “I have been increasingly perturbed over the blatant disparity between the major role which Negro women have played and are playing in the crucial grassroots level of our struggle and the minor role of leadership they have been assigned.” She continued promoting this platform in her 1964 legal memorandum to add “sex” as a protected category in the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Though Murray’s publishing largely ended when she joined a seminary and became an Episcopal priest in 1977, her activism advanced racial and gender equality in both legislation and the civil rights movement. Her memory resonates through the continued republishing of her works and is apparent at the University of North Carolina through widespread support for renaming Hamilton Hall to Pauli Murray Hall in her honor. -Nicole Harry |

| Out of the Archives |

|

View

No items found

|

| Graduate Student News |

ViewHistory Graduate Students establish European History Seminar

The goals of this group are simple: to provide a “safe space” for graduate students to present their work, test ideas, and ask questions of each other without the pressures of more formal seminars held by the department. Though originally created with graduate students in European history in mind, the seminar has expanded beyond a narrow regional focus and has hosted presentations on British and French colonialism in Africa, Russian and Soviet history, and diplomatic relations between West Germany and China. Till and Oskar emphasize that the European History Seminar’s highest priority is to offer an accessible setting for graduate students to practice being involved in an intellectual community and gain confidence engaging with each other’s work, without being tied to narrow definitions of “European” scholarship. Oskar highlights the importance of support among seminar: “There is a social aspect to the group. We get together as academics and friends, experiment with our ideas, and have a community we can trust with our work.” Coronavirus restrictions forced the seminar online in spring 2020, but this shift also allowed for the program to expand. Through pre-existing connections between the University of North Carolina (UNC) and King’s College London’s (KCL) History Departments as well as UNC’s Collaborative Online Integrated Learning (COIL) program, the seminar is now open to graduate students from KCL and Charles University, Prague. In order to accommodate these international scholars, the seminar’s monthly meetings alternate between in-person meetings on UNC’s campus and online sessions with the KCL and Charles University students. Additionally, understanding how to run the seminar effectively on Zoom has allowed for additional benefits, such as the involvement of UNC graduate students currently abroad or not on campus. In 2021, Morgan Morales and Alison Curry took over leadership of the European History Seminar and are hoping to expand its membership by including more early modern and medieval scholars. Additionally, as the program’s relationships with KCL and Charles University develops, members of the Seminar hope to receive funding support for a scholar exchange between KCL and UNC, as well as potentially organize an online conference among KCL, UNC, and Charles University. All four leaders of the European History Seminar value the community and support it provides. Morgan notes: “I always learn something new from each seminar, and I enjoy getting to learn more about what my colleagues are working on,” and adds that “we rarely talk about our work in depth with others, so its fun to see the actual inner workings of my colleagues’ and friends’ projects.” Alison adds that “I always leave the working group with something new to bring back to my own work.” When asked about a favorite memory from their work with the group, all four leaders mentioned a paper presented by Pasuth Thothaveesansuk on the role of pandas in diplomatic relations between West Germany and China. Pasuth’s presentation developed into a five-hour conversation amongst seminar participants, and with comments and revisions from the group Pasuth presented his paper at the German Studies Association conference in fall 2021. In the two years of its existence, the European History for Graduate Students has successfully created a space for graduate students to gain confidence in their involvement in an intellectual community. The group now crosses disciplines and continents, and only hopes to continue being an accessible platform for UNC history graduate students to share their work with their colleagues and community. Update from the Director of Graduate StudiesMost of our graduate students returned to campus this fall. Others who had put their research on hold were finally able to begin their travel and take up their fellowships. Because they will need extra time to complete their degrees after pandemic-related delays, the History Department did not admit a new class. We did, however, hold our first comprehensive orientation for the graduate students beginning their second year. This was an experiment, trying to figure out what new cohorts would need in the future. It was a very successful day, and kudos go to those who organized it: students Morgan Morales and Megan McClory and Student Services Coordinator Diana DeProphetis. The History Department has been reviewing our program as the demands for historians shifts and the interests of our students expand. We have made comprehensive examinations consistent across all fields, and we are trying a new admissions process that allows more connections across fields. We continue our long commitment to history beyond classrooms. This year, three of our students are working with Carolina Public Humanities. Alexandra Odom is a Maynard Adams Fellow, part of a select cohort of graduate students working to build relationships with the broader community. Matt Gibson and Craig Gill are part of the Humanities for the Public Good Graduate Fellows program, helping North Carolina institutions collaborate with UNC to build skills. This year, two of our graduate students explored history work outside the classroom and the archives with the Mark Clein Graduate Summer Internship Award. Craig Gill interned at the UNC Chapel Hill Office of International Student and Scholar Services helping them identify some of the greatest needs that graduate students face at UNC. Nurlan Kabdylkhak participated in the Endangered Archives Program in Kazakhstan helping to preserve a unique collection of books and manuscripts that came to light only two years ago. Our students continue to do research appreciated at the highest levels. History graduate students received 5 of UNC’s 6 prestigious Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Fellowships for research abroad (China, Guatemala, Mexico, Senegal, South America, and Turkey.) These are only some of the 19 students whose work will take them away from UNC on grants, awards, and fellowships for the spring semester. For a more comprehensive list of the numerous awards our graduate students have received, see https://history.unc.edu/graduate-student-awards/. -Sarah Shields, Director of Graduate Studies |

| Undergrad News |

|

View

No items found

|

Gifts to the History Department

The History Department is a lively center for historical education and research. Although we are deeply committed to our mission as a public institution, our “margin of excellence” depends on generous private donations. At the present time, the department is particularly eager to improve the funding and fellowships for graduate students.

Your donations are used to send graduate students to professional conferences, support innovative student research, bring visiting speakers to campus, and expand other activities that enhance the department’s intellectual community.

|

To make a secure gift online, please click “Give Now” above.

The Department also receives tax-deductible donations through the Arts and Sciences Foundation at UNC-Chapel Hill. Please note in the “memo” section of your check that your gift is intended for the History Department. Donations should be sent to the following address:

UNC-Arts & Sciences Foundation

Buchan House

523 E. Franklin Street

Chapel Hill, NC 27514

Attention: Ronda Manuel

For more information about creating scholarships, fellowships, and professorships in the Department through a gift, pledge, or planned gift please contact Ronda Manuel, Associate Director of Development at the Arts and Sciences Foundation: ronda.manuel@unc.edu or (919) 962-7266.

This spring, Professor Chad Bryant published his second book with Harvard University Press. Prague: Belonging in the Modern City has received favorable reviews in The Economist and the Times Literary Supplement, bringing his work to a broader public. As Bryant explained in an interview this fall, he wrote this book for both experts and interested laypeople — particularly those planning a trip to Prague, a city that has become an essential stop on any tourist’s Central European itinerary. Its architecture looks familiar enough to a foreign visitor, while its history and culture are unfamiliar enough for these visitors to attach whatever symbolic meanings they like to its buildings and landscape. At the same time, however, Prague has served as the symbolic center of the nation since the birth of the Czech nationalist movement. Successive political movements and ruling regimes have legitimated and consolidated their power by transforming the city’s physical and symbolic landscape. Unlike most other European capitals, where wartime destruction and postwar reconstruction have partially obscured this history, tourists in Prague can encounter the architectural legacies of multiple ideological projects on a short walk. Their guide books are likely to interpret this landscape for them by means of a national story — the story of a nation with a glorious past that fell into decline under foreign rule, resurrected its culture and renewed its independence, but was abandoned to Nazi occupation and then shut up behind the Iron Curtain, only to liberate itself again and reclaim its rightful place in a free Europe.

This spring, Professor Chad Bryant published his second book with Harvard University Press. Prague: Belonging in the Modern City has received favorable reviews in The Economist and the Times Literary Supplement, bringing his work to a broader public. As Bryant explained in an interview this fall, he wrote this book for both experts and interested laypeople — particularly those planning a trip to Prague, a city that has become an essential stop on any tourist’s Central European itinerary. Its architecture looks familiar enough to a foreign visitor, while its history and culture are unfamiliar enough for these visitors to attach whatever symbolic meanings they like to its buildings and landscape. At the same time, however, Prague has served as the symbolic center of the nation since the birth of the Czech nationalist movement. Successive political movements and ruling regimes have legitimated and consolidated their power by transforming the city’s physical and symbolic landscape. Unlike most other European capitals, where wartime destruction and postwar reconstruction have partially obscured this history, tourists in Prague can encounter the architectural legacies of multiple ideological projects on a short walk. Their guide books are likely to interpret this landscape for them by means of a national story — the story of a nation with a glorious past that fell into decline under foreign rule, resurrected its culture and renewed its independence, but was abandoned to Nazi occupation and then shut up behind the Iron Curtain, only to liberate itself again and reclaim its rightful place in a free Europe.  For the final two chapters of his book, Bryant was able to draw on personal interviews conducted with his subjects in addition to their written work. In “Communist City,” he examines how Hana Frejková, an actress whose father was a leading Party economist executed in the infamous Slánský trial, succeeded in both fashioning an independent identity and expressing herself artistically despite facing both political repression and social exclusion. Her memoir describes the journey of a loner — a solitér, as she continually described herself in interviews — who finds acceptance and fulfillment through art and through her family. Finally, “Global City” discusses the experiences of Duong Nguyen, whose parents were among the many Vietnamese students and workers who moved to the Czech Republic under state socialism and stayed on after 1989. Her thoughtful and forthright blog about living between two cultures presented a distinct perspective ignored by the broader Czech public as well as the traditional leadership of the Vietnamese community. It offered a picture of Prague as a cosmopolitan city despite itself, whose diversity and pluralism was too frequently overlooked or denied.

For the final two chapters of his book, Bryant was able to draw on personal interviews conducted with his subjects in addition to their written work. In “Communist City,” he examines how Hana Frejková, an actress whose father was a leading Party economist executed in the infamous Slánský trial, succeeded in both fashioning an independent identity and expressing herself artistically despite facing both political repression and social exclusion. Her memoir describes the journey of a loner — a solitér, as she continually described herself in interviews — who finds acceptance and fulfillment through art and through her family. Finally, “Global City” discusses the experiences of Duong Nguyen, whose parents were among the many Vietnamese students and workers who moved to the Czech Republic under state socialism and stayed on after 1989. Her thoughtful and forthright blog about living between two cultures presented a distinct perspective ignored by the broader Czech public as well as the traditional leadership of the Vietnamese community. It offered a picture of Prague as a cosmopolitan city despite itself, whose diversity and pluralism was too frequently overlooked or denied. For the past six years, the Sallie Markham Michie Trust has awarded funding to a graduate student within the University of North Carolina’s History Department. Sallie Markham Michie established the trust before her death in 1993, and it continues to be overseen by the Orange County Daughters of the American Revolution and the Magna Carta Dames Society, in both of which she was an active member. Over 25 years after its creation, the trust continues her legacy.

For the past six years, the Sallie Markham Michie Trust has awarded funding to a graduate student within the University of North Carolina’s History Department. Sallie Markham Michie established the trust before her death in 1993, and it continues to be overseen by the Orange County Daughters of the American Revolution and the Magna Carta Dames Society, in both of which she was an active member. Over 25 years after its creation, the trust continues her legacy.

Anna Pauline “Pauli” Murray (1910-1985) was one of the most remarkable intellectuals and human rights advocates of the 20th Century. She also had strong personal ties to North Carolina, to UNC, and to the intellectual work carried out in this building. These reasons support the proposal to rename our building in Pauli Murray’s honor.

Anna Pauline “Pauli” Murray (1910-1985) was one of the most remarkable intellectuals and human rights advocates of the 20th Century. She also had strong personal ties to North Carolina, to UNC, and to the intellectual work carried out in this building. These reasons support the proposal to rename our building in Pauli Murray’s honor. A shared pivotal experience in every early-graduate school career, it seems, is one’s first seminar. The professors know each other, older graduate student ask insightful questions, and first and second years don’t know where to begin. It was on the basis of these experiences that Oskar Czendze and Till Knobloch, two Ph.D candidates in modern European history, decided to found the European History Seminar for Graduate Students in January 2019.

A shared pivotal experience in every early-graduate school career, it seems, is one’s first seminar. The professors know each other, older graduate student ask insightful questions, and first and second years don’t know where to begin. It was on the basis of these experiences that Oskar Czendze and Till Knobloch, two Ph.D candidates in modern European history, decided to found the European History Seminar for Graduate Students in January 2019.