Spring 2022 – Archives

| Expand All | Collapse All |

| Department News |

ViewUNC Supports Ukraine

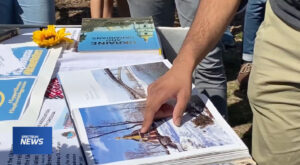

When asked about her motivations for organizing the event, Huselja responded, “After the invasion, I had a number of students who talked to me after class about what was going on. I also noticed that besides them, other people I knew were surprised that Russia even invaded to begin with. With so much confusion floating around, I and my colleagues thought such an event would be a good way for people to have an open space for discussion, ask any questions, and hopefully come away more informed about what was going on.” In order to address these concerns, the teach-in consisted of an open floor, where audience members were able to ask questions and share their emotions and responses to the war. Professor of History Chad Byrant delivered a keynote address, and the panelists included faculty from the Departments of Anthropology, History, and Political Science. Also participating were Oleh Wolowyna, a visiting fellow from Ukraine, Suzie Colbern, Associate Director of the Triangle Institute for Security Studies and a historian of NATO, and Elena Trubina, a visiting scholar from Ural Federal University in Ekaterinburg. Commenting on the motivation behind the event, Thothaveesansuk, a doctoral candidate in Cold War history, noted, “One thing that stood out to me about the invasion was that Putin attempted to justify it based on a series of lies and disinformation about history. As historians ourselves, I felt like we were in a position to help counter the narrative even in a small scale, as well as help our community understand and process what had happened.” Echoing this theme in his keynote speech, Bryant stressed the importance of responsibly analyzing and filtering the mass of information and opinions circulating about the war, especially in social media.

Since the teach in and rally, other events have also been hosted on campus to educate the community about the ongoing war, including a roundtable of Ukrainian scholars and professionals as well as a benefit concert by a local Ukrainian band. As Huselja highlights, “It is essential, for Ukrainians’ sake, that Ukraine doesn’t simply fall off our news radar or that we become numb to what is going on. Events are a small way to educate people and motivate them to care and act in productive ways — whether that’s through donations, contacting representatives, etc.” The event, which benefited from a lively and engaged audience, highlights the contribution that historians can make, however small, to combating disinformation and speaking truth to power. It reflects the best of a longstanding tradition in the History Department of offering historically informed analysis and context about current events. –Nicole Harry Fulbright-Hays Recipients Return to Research in AfricaAfter navigating almost three years of a global pandemic, two graduate students of the History Department, Laura Cox and Abby Warchol, received the Fulbright-Hays fellowship and are finally able to resume their research in Africa. Both scholars recognized the reception of this award as the driving force able to get them back into their dissertation projects and, as Warchol states clearly: “Quite simply, the Fulbright-Hays fellowship has made it possible to do my dissertation research. Since the archives I use in Senegal have not digitized their holdings, the inability to travel meant that I was unable to do much exploratory research that would have been helpful in conceiving my dissertation project and research plan.”   Both Cox and Warchol look forward to the rest of their research this year and appreciate the opportunity provided by the Fulbright-Hays to return tangibly to their work in Africa after over two years away. –Nicole Harry New Initiative Offers a Fresh Perspective Sturkey got the idea in late Fall 2019, when the university reached a deal to pay a neoconfederate group several million dollars to take custody of the “Silent Sam” Monument, which by then had been removed from campus. He had just finished teaching a course called “Race and Memory at UNC,” which partly addressed recent controversies about monuments and buildings glorifying university figures with ties to white supremacists causes. “I taught that class to educate our communities,” he recalls. “The university wasn’t doing enough to empower students and community members. What struck me was the tremendous hunger for this kind of historical inquiry.” The class met on Wednesday nights. It attracted a large enrollment, with 100 students and 20 alumni. “It was helpful for people who were thirsty for news and history. It showed that there is a demand among multiple campus constituencies for a critical reappraisal of the dominant narratives about this university.” The course, which was taught Pass/Fail for one credit hour, was not designed to place insurmountable burdens on the participants. Its purpose, instead, was to empower students and alumni to explore the university’s history in new ways. The results amazed Sturkey. “I had students doing podcasts. Walking tours. Thinking about history, and the university, in ways that were new, cutting-edge, in ways that hadn’t been done before.” When asked to explain what empowering students means in practice, Sturkey does not mince words. “Imagine an African American student, perhaps a teenage girl, coming to Carolina as a freshman, and being given a room in Grimes Hall. We have documents showing that the building’s namesake, John Bryan Grimes, was involved in sex slavery. He was buying and selling teenage black girls to rape them. What do you do with a 18 year old black girl who is learning in a building named after a guy like that?” Sturkey notes that part of the controversy surrounding the effort to engage with racism at UNC, and especially the politics of renaming buildings and monuments, rests on false accusations made by neoconfederate groups about the harm of “erasing history.” Exploring the history of racism at Carolina, he stresses, represents the exact opposite. By way of example, Sturkey points to the decision made in 1967 to dedicate the campus bookstore to Josephus Daniels, perhaps the most prominent North Carolina politician to support the infamous white supremacist massacre and riot in Wilmington in 1898, an event that destroyed the city’s African American middle class. “The people who say you can’t erase history, they have no clue how much history has already actually been erased. Changing bulding names, or subjecting historical figures to careful scrutiny, is less about the namesakes, than about the people who made the decision to name the building. The bookstore naming happened right after desegregation in higher education. It’s not a coincidence.” Sturkey stresses how important it is that such a historical reckoning proceed from the state’s flagship university. Nodding to far-reaching initiatives engaging with the history of racism and higher education in the South at the University of Virginia and the College of William & Mary, he points out that the UNC campus is “the most carefully curated commemorative landscape in the state of North Carolina.” Citing the teaching and scholarship of Prof. Fitz Brundage on commemoration and memory, he notes just how saturated Carolina is with historical memory, citing “the carefully curated names, the organization of it. If you are looking for monuments presenting a curated vision of the past, they’re everywhere. And in this carefully curated historical landscape, only certain kinds of people get to play a role.” Promoting a broader, richer, and more just understanding of UNC’s history is not only the business of historians and archivists, Sturkey suggests, “because these conversations are taking place across the South, across the country, across the world. If we want to have any role in them, we have to start by looking at ourselves.” Initiatives such as the Historical Truth & Justice Action Fund, that give students the chance to retell the university’s history from a fresh angle, will amply repay the modest support it has received from the university. In advocating for continued support from the administration, alumni, and the community at large, Sturkey makes his case succinctly: “We have to engage with our history as a university in a responsible, forward looking way, in a way that befits the stature of an ambitious research university.” |

| Faculty Spotlight |

ViewRussia and Ukraine I met with Dr. Raleigh in mid-April to get his perspective both on Russia’s war in Ukraine both as a historian and as someone who has spent time in both countries. Q. Did the Russian invasion of Ukraine surprise you? Q. How do you understand what might have motivated Putin’s decision? You often hear people say that he is trying to reestablish the Soviet Union, or the Russian Empire. What do you think about this? While Putin laments the fall of the Soviet Union, he takes a very negative attitude toward communism, and especially toward the Russian Revolution. Official statements on the 100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution five years ago described it as a negative event that robbed Russia of victory in the First World War. State commemorations that year focused on the First World War, not the Russian Revolution — because if revolution was justified in 1917, it might be justified today if people oppose the government! Putin has also argued that the Bolsheviks disrupted Russian unity. Just before the invasion, he argued that the idea of an independent Ukrainian nationality was an artificial product of Bolshevism and the federated Soviet state. Of course, this isn’t true at all. Ukrainian nationalism was among the many national movements that emerged in nineteenth-century Europe. Ukrainians pushed for autonomy immediately when the Russian Revolution broke out, and in fact declared independence shortly thereafter. The Ukrainian state was later absorbed into the Soviet Union, but it was not a creation of the Soviet Union — it was there first. Q. How does the memory of the Second World War affect how people in Russia, Ukraine, and the rest of the world understand and talk about this war? The Second World War looms large in Russian historical memory, since the Nazi invasion resulted in the deaths of twenty-seven million Soviet citizens. So by talking about neo-Nazis in Ukraine, and by making reference to historical events, Putin is trying to mobilize public opinion in favor of his aggressive policy. Yes, it’s true that some peasants in western Ukraine welcomed the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union because they were told that they would get their land back, that the churches would be reopened, and that Stalin would be overthrown. And it’s true that some right-wing Ukrainian nationalist insurgents fought against Soviet power until the late 1940s. But ironically, this was never part of the Soviet historical narrative, and it wasn’t discussed publicly until perestroika. Q. Do you think that historical analogies are useful in trying to understand this war? Why do you think they come up so often? After Putin came to power, he based his popularity on economic success and stability. After the financial crisis in 2008, though, this momentum couldn’t be sustained, and the evidence shows that Putin’s strategy shifted. He sought to build legitimacy by restoring Russia’s power on the world stage, and he had some small successes — the wars in Georgia and Abkhazia, the Olympics in 2014, and the annexation of Crimea. But the invasion of Ukraine indicates that this wasn’t sustaining itself. I interpret it as an act of desperation. By drawing focus on an external enemy and stirring up fears of Nazism, he can take attention away from the problems in Russian society. But can it work? I’m doubtful. Ukraine, on the other hand, was able to come up with an official narrative, and it’s a narrative of victimhood, repression, and suffering under both the tsars and the Soviets. The current invasion fits into this narrative very well. Putin’s actions will not only bolster the Ukrainian narrative of victimhood, it will likely strengthen Ukraine’s national identity. This began already after the annexation of Crimea and the conflict in Donetsk and Luhansk. In 2017, I did research in Dnipro, a city in eastern Ukraine where Russian is widely spoken. I met many people who spoke both languages and hadn’t considered themselves either Russian or Ukrainian, who began to identify themselves as Ukrainian because of the threat posed by Russia. Q. Why was Putin so surprised by the Ukrainian resistance? Was he a victim of his own mistaken beliefs? NATO and the West have made mistakes. NATO should have been abolished after the Cold War. It was a Cold War organization, aimed against the Soviet Union. The Ukrainian state has made mistakes as well. I was at an archive in Dnipro in 2017, and I had to fill out a registration form in Ukrainian. Since it was a state institution, they wouldn’t accept forms in Russian. They had a laminated template to help you fill the form out in Ukrainian, because otherwise most of the visitors wouldn’t have been able to do it, including the local people. And then we all went and turned it in to the Russian-speaking staff. I found this a little absurd. So, it is true that the government has taken Ukrainianization measures that I don’t think are necessary. There are legitimate criticisms to be made of NATO’s actions and those of the Ukrainian government, but none of them justify the invasion in any way whatsoever. Russian scholars and scholars of Slavic studies have attempted to explain Russia’s interests, its security concerns, and the perspective of its government with regard to Ukraine, and in some cases may have gone too far. On the day of the invasion, I posted on social media saying that this was a day of infamy. I wrote that this was a sign of Putin’s waning popularity, and that the fighting would be horrific, but that it would unite the people of Ukraine like never before. And I was scolded by a retired high-ranking US diplomat, who said that Putin just borrowed the playbook that the United States used for Iraq. Q. What’s your specific problem with that analogy? Immediately after the invasion, some British colleagues circulated a petition that, among other things, asked Western countries not to send arms to Ukraine in order to prevent a bloodbath. Well, what would the consequences of that have been? Putin would have installed a puppet in Kyiv, and there would likely still have been a bloodbath. Q. I’m interested in what you think about the argument that Putin is threatened by Ukrainian democracy. If a flourishing, Western-oriented democracy were established next door to Russia, this argument goes, it would undermine Putin’s regime by demonstrating to Russian citizens that they, too, could live in a freer and more prosperous society. It sounds plausible, but I wonder if it doesn’t go too far in attributing beliefs to Putin that he doesn’t necessarily hold. The war has certainly had a demoralizing effect on many Russians. My friends in Russia — some of whom I’ve known since I was a student — are depressed, they’re angry, they’re horrified. Some of their adult children have fled the country, and they don’t know when they’ll see them again. When I talk to them on FaceTime, you can see their tired faces and swollen eyes, and it’s heartbreaking. But Russians opposed to the conflict are engaging in small acts of defiance, even though the risks are significant. Q. How do you think this war will affect the fields of Russian, European, and Soviet history? Historians studying Russia will look for topics that can be researched elsewhere, so we may see a revitalization of work on the Russian diaspora, for example. I recently talked with a colleague at another university, and she mentioned that her Russian history course filled up immediately. This crisis will likely increase interest in Ukrainian history as well, and in Eastern European history more generally as a part of European history. Q. How have your own research plans been affected? I will go back as soon as it’s possible, although I’ll have to apply for another visa. I’ve never had a problem getting a visa in the past, but the things I’ve posted on social media may make that more difficult now. During the Soviet days, I was always able to get a visa, but I feel that it’s different now. In those times, you could figure out how the system operated, but now foreign scholars really don’t know what to expect. –Mira Markham |

| Alumni Spotlight |

ViewSchwarzman Scholar Reflects on Studying History at UNC

The desire to embrace challenge runs through Zahn’s academic career at UNC. A Pennsylvania native, he wound up at Carolina with the support of the Robertson scholarship and added to that a Truman scholarship, awarded to the nation’s top public service scholars, just two years later. From the start, he found himself attracted to classes which dealt with issues affecting people’s everyday lives, leading him to major in political science. However, after completing most of the requirements by the end of his sophomore Fall, Zahn was left wanting more. “I appreciated political science and loved my professors but didn’t feel particularly pushed by the courses. I wasn’t improving much as a writer, and didn’t feel like I was reading the substantial, weighty books I expected in college.” Freshman spring at Carolina, Zahn had enrolled in Prof. Matt Andrews’s history course on “Race, Basketball, and the American Dream.” “I enjoyed it immensely. It opened my eyes to how much I can take from just one course. Ultimately, it was the impetus for my decision to add history as a second major. Once I decided to steep myself into history, there was no looking back. I took four history courses the next semester, including an independent study with Duke’s Prof. Malachi Cohen, in which I wrote an intellectual biography of Judah Magnes, the great American Jewish pacifist and non-conformer.” Recalling the independent study as “one of the most intimidating academic experiences of [his] life,” Zahn nevertheless found himself hooked. Enrollment in Prof. Molly Worthen’s course on American intellectual history that same semester sealed the deal: At the end of sophomore year, Zahn declared history as his second major. Zahn credits history courses with getting him to think critically, and historically, about his surroundings. His enthusiasm could be infectious, as one of his instructors, Prof. Eren Tasar, noted: “I could only think of Sam as a colleague, not a student. He took our class discussions into directions I never could have anticipated, and his research paper on the Israeli Supreme Court is one of the best I have read in my career. I consider myself lucky and privileged that he chose to take one of my courses.” Zahn’s gift for historical inquiry was hardly confined to the classroom. Two incidents that rocked campus in 2019 are a case in point. In April 2019, antisemitic flyers were found posted at Davis Library. Around the same time, a rapper used antisemitic lyrics while performing at a conference on campus. These incidents led Zahn to join forces with a doctoral candidate in German history, Max Lazar, to develop a course called “Confronting Antisemitism.” The course was organized around a series of guest lectures delivered from a variety of disciplines. It proved to be a great success, not least because it helped contextualize modern antisemitism within the context of the broader phenomenon of racism. More history courses only deepened Zahn’s interest. As COVID hit the Spring of his sophomore year, Zahn opted to enroll in a History 398 research seminar taught virtually by Prof. Fitz Brundage on monuments, memory, and commemoration. Zahn’s research paper focused on the history of Rabin Square in Tel Aviv, commemorating assassinated Israeli prime minister Yitzah Rabin. That summer, before his study abroad in Jerusalem, Zahn found himself living and interning in Tel Aviv, only five minutes away from the monument to Rabin. “I lived right next to his plaza and walked by it every day. I kept thinking: ‘No one pays attention to this place, yet it’s so rich with historical memory.’” Zahn recalls the power of this “profound experience of studying something and having it change how you interact with your everyday world, of delving into research that changes the way you carry yourself in the world.” Zahn credits history as one of the outstanding features of his Carolina experience. “When I looked back at my transcript to see what courses were worth taking, and looked back at courses that profoundly altered my worldview, history classes were at the top of the list. I really wish I would’ve taken more of those. History provided a great community.” When asked about his long-term plans, Zahn could only say that he wasn’t sure: He was headed to the American Jewish Committee in Washington for the summer, and had a flight to catch to Abu Dhabi at the end of August. |

| History in Our World |

|

View

No items found

|

| Out of the Archives |

|

View

No items found

|

| Graduate Student News |

ViewResearching Religion in Russia Q. Can you tell us about your dissertation research? The subject of religion in the Russian Empire, and specifically of Russia’s relationship to the Holy Land, is one that hasn’t been explored until recently. Under the Soviet Union, of course, it was difficult to access the necessary materials, and for a few decades after the Soviet Union’s collapse scholars were interested in other subjects. But now, the political importance of the Orthodox Church is increasing in contemporary Russia. The current government is trying to connect Russian identity both more closely to Orthodoxy and to the imperial past, so this is a topic that more people are becoming interested in. Q. How did your research trip start? When I got to Moscow, the Archive of Foreign Politics was still operating on a reduced schedule because of Covid-19. You had to make reservations two months in advance. Fortunately, I had a contact in Russia who got me reservations for the end of January and February. It was still difficult, though, because after you put in your requests for material, it takes the archive several days to prepare it for you. So you might finish everything you’ve ordered on Friday and then on Monday, even though you have a reservation, you won’t have anything to work with. On those days, I used my time in the archive to go through the finding aids. Although the finding aids do provide some indication of how many boxes and pages are contained in each item, you still don’t exactly know what you’re going to find until you open up the files. So in each order, I’d ask for both items that I knew would have useful material and ones that I wasn’t quite sure about. Q. You kind of have to find your way around a new archive. I also worked at the Lenin Library, which was a nice change of pace from the archive, because here, I could just go in and order books or newspapers, and they’d be delivered by the next day at the latest. They have a huge collection of published material, and I tried to collect as much as I could here. I was also gathering material for future projects, since I didn’t know when I’d next get the chance. Some sections of the Lenin Library are located in a former palace, as well, so the reading room is beautiful. Q. What was your plan for the rest of the year? Q. But that’s not what happened. That day, another researcher at the archive pulled me aside during the lunch break and told me how ashamed and appalled she was. She didn’t understand how this could be happening. But when I went home that evening, it was as if nothing had happened. Nobody was on the streets until that night, when I heard people chanting “No to war!” from my apartment. It was a relief to hear that some people in Moscow opposed this. It was difficult to get up the next day and go to work as usual in the library. It was a surreal feeling — the war had started, but around me, it looked like nothing was wrong. By that evening, the United States and the EU countries had begun announcing sanctions. Although I wasn’t in any physical danger, I knew that soon I might not be able to access my bank account. I could borrow money from my friends if there was an emergency, but I didn’t want to put them in that position. When I heard that there were plans to shut down international flights from Russia, though, I knew I had to get out. I booked a ticket to Istanbul and left on Saturday, February 26th. Q. How did this experience affect you and your research? I was also troubled by some of the calls for Western academics to disengage from Russian institutions. Of course, I understand why someone wouldn’t want to associate themselves with the Russian government, or with people that openly support it, but I recognize that Russian scholars place themselves and their families at risk by coming out publicly against the regime. Q. What are your thoughts about how this will affect Russian history as a field? It seems that this conflict may have sharpened our focus on Russian history as imperial history, which is something that I’m interested in. We have to understand the history of the Russian Empire as one of many peoples and many institutions. The imperial government and the Russian Orthodox Church did make efforts to impose a Russian identity on its subjects, but they remained diverse. There was diversity within the Orthodox Church and within the Russian ruling class as well. At the same time, there are important differences between the Russian Empire and, say, the British or French empires. The Romanovs were more interested in expansion than in extracting resources, and race played a different role. Q. Do you see any connections between your research and the current situation? Q. What are your future research plans? I also successfully applied to participate in the Summer Research Lab at the University of Illinois, so I’ll be traveling to Urbana-Champaign later this year as well. It’s possible that they might have copies of archival material and periodicals that I haven’t been able to access yet. Finally, I’m working with ASEEES to see if I can use the Cohen-Tucker Fellowship to fund research in the UK and in Finland. Great Britain had a presence in Palestine at this time too, of course, so I’m interested in seeing what British officials had to say about these Russian Orthodox societies and pilgrims arriving from Russia, or what British travelers may have written in their accounts. Since Finland was also part of the Russian Empire, their National Library also has collections of Russian government publications. I’m very fortunate that my advisor, Dr. Louise McReynolds, completed her dissertation before Western scholars had access to Russian archival sources. She knows how to do research without relying on archives. When I came back to the US, she reassured me that my topic was solid and I could still complete my research. In a sense, it’s as if we’re back in the 1980s. Of course, we do have the internet and I’ve been able to look at some digitized documents and publications available online. But I do hope to go back some time soon, although I don’t know when I’ll have the opportunity. I love traveling to Russia, because all the archivists and academics I’ve met have been very helpful, and I hope to stay in touch with them. –Mira Markham Cristian Walk Receives Award for Graduate Teaching Assistant Excellence The Tanner Award for Excellence in Undergraduate Teaching was founded in 1952 by Sarah Tanner and her brother, Kenneth Spencer Tanner, in memory of their parents. The award was established to recognize excellence in inspirational teaching of undergraduate students, especially those in their first and second years of their undergraduate career. In 1990 UNC expanded the award to include the work of graduate teaching assistants. This year, awardees included graduate teaching assistants from the Departments of Computer Science, Psychology, and Political Science. The presence of a historian in this competitive field testifies not only to Walk’s talent as an educator, but also to the fact that, at its best, historical pedagogy emphasizes patience, compassion, and building relationships with their students. Reflecting on his own time in the classroom, where he developed the skills recognized by the Tanner Award, Walk comments that “the most rewarding part about teaching undergrads is building a meaningful relationship with students and giving them the tools to learn on their own.” He adds, “It is especially rewarding to see students using the tools we teach them to craft their own arguments – especially when they challenge dominant narratives, including those we propagate.” Walk received the Tanner Award while teaching a course on conspiracy theories and historical truth, and he advises his students to “think critically and approach the classroom and entire university system with a healthy dose of skepticism. How does power shape the types of arguments we hear in the classroom and those who make them? That type of question should inform how students approach education and is one that I wish I knew long ago.” While honored to have received an award for his teaching skills, Walk also wants to use it as a way of drawing attention to the hard work of his graduate student colleagues in the Department of History, who also deserve recognition for their pedagogy and empathy toward students. On this note, he draws attention to the ongoing plight of graduate students in the department: “If UNC really wanted to honor their teachers, they would pay all of us a living wage, not give out a few awards.” –Nicole Harry |

| Undergrad News |

|

View

No items found

|

Gifts to the History Department

The History Department is a lively center for historical education and research. Although we are deeply committed to our mission as a public institution, our “margin of excellence” depends on generous private donations. At the present time, the department is particularly eager to improve the funding and fellowships for graduate students.

Your donations are used to send graduate students to professional conferences, support innovative student research, bring visiting speakers to campus, and expand other activities that enhance the department’s intellectual community.

|

To make a secure gift online, please click “Give Now” above.

The Department also receives tax-deductible donations through the Arts and Sciences Foundation at UNC-Chapel Hill. Please note in the “memo” section of your check that your gift is intended for the History Department. Donations should be sent to the following address:

UNC-Arts & Sciences Foundation

Buchan House

523 E. Franklin Street

Chapel Hill, NC 27514

Attention: Ronda Manuel

For more information about creating scholarships, fellowships, and professorships in the Department through a gift, pledge, or planned gift please contact Ronda Manuel, Associate Director of Development at the Arts and Sciences Foundation: ronda.manuel@unc.edu or (919) 962-7266.

On February 24, 2022, Russia invaded Eastern Ukraine and catalyzed a war. Individuals and communities internationally mobilized to support Ukraine and its people in any way they could, including at UNC. For the academics and educators at UNC who specialize in the region and its history, this support took the shape of a teach in and rally held on March 4, 2022. This event was organized by three Ph.D candidates in the Department of History, Alma Huselja, Pasuth Thothaveesansuk, and Nicole Harry, and a Master’s student in the Global Studies Program, Kathryn Goodpaster.

On February 24, 2022, Russia invaded Eastern Ukraine and catalyzed a war. Individuals and communities internationally mobilized to support Ukraine and its people in any way they could, including at UNC. For the academics and educators at UNC who specialize in the region and its history, this support took the shape of a teach in and rally held on March 4, 2022. This event was organized by three Ph.D candidates in the Department of History, Alma Huselja, Pasuth Thothaveesansuk, and Nicole Harry, and a Master’s student in the Global Studies Program, Kathryn Goodpaster.  The teach-in was followed by a rally held at Polk Place in support of Ukraine that included guests from the Ukrainian Association of North Carolina. In addition to speakers and communal conversation, participants also signed a Ukrainian flag that is now displayed in UNC’s FedEx Global Education Center. Reflecting on both the teach in and the rally, Thothaveesansuk added, “I was happy to see that we had not just fellow graduate students in attendance, but also undergraduates, faculty, staff, and other members of the community.”

The teach-in was followed by a rally held at Polk Place in support of Ukraine that included guests from the Ukrainian Association of North Carolina. In addition to speakers and communal conversation, participants also signed a Ukrainian flag that is now displayed in UNC’s FedEx Global Education Center. Reflecting on both the teach in and the rally, Thothaveesansuk added, “I was happy to see that we had not just fellow graduate students in attendance, but also undergraduates, faculty, staff, and other members of the community.” As a traveler and an intellectual, Sam Zahn ’22 is always on the move. After graduating from UNC with a double major in history and political science on May 9, he headed to southern Utah for a real-life adventure in the wilderness. Having fun might have been on the agenda, but it wasn’t the point: the trip was organized by the Robertson Scholarship Leadership Program for its recipients to push themselves and each other in an environment far beyond the classroom. Donning a winter jacket in May was not Zahn’s initial plan for celebrating graduation. “Initially, I was really skeptical,” he comments. “We went out there for a week and I am not a backpacker.” When the sun set on the first night, he changed his mind. “The stars,” he recalls, “were unbelievable. There were stars you could see that I didn’t know existed. You could see the sky moving.” For Zahn the trip ended up being well worth the hardship. “It really gave me a very high opinion of outdoor education. The clarity of mind it can afford is really something unique.” Zahn will take these experiences with him as he charters more unfamiliar territory in China this upcoming year. Having recently been named a Schwarzman Scholar, he joins a handful of UNC students who have received the prestigious scholarship, which funds a master’s degree in global affairs at Beijing’s Tsinghua University.

As a traveler and an intellectual, Sam Zahn ’22 is always on the move. After graduating from UNC with a double major in history and political science on May 9, he headed to southern Utah for a real-life adventure in the wilderness. Having fun might have been on the agenda, but it wasn’t the point: the trip was organized by the Robertson Scholarship Leadership Program for its recipients to push themselves and each other in an environment far beyond the classroom. Donning a winter jacket in May was not Zahn’s initial plan for celebrating graduation. “Initially, I was really skeptical,” he comments. “We went out there for a week and I am not a backpacker.” When the sun set on the first night, he changed his mind. “The stars,” he recalls, “were unbelievable. There were stars you could see that I didn’t know existed. You could see the sky moving.” For Zahn the trip ended up being well worth the hardship. “It really gave me a very high opinion of outdoor education. The clarity of mind it can afford is really something unique.” Zahn will take these experiences with him as he charters more unfamiliar territory in China this upcoming year. Having recently been named a Schwarzman Scholar, he joins a handful of UNC students who have received the prestigious scholarship, which funds a master’s degree in global affairs at Beijing’s Tsinghua University.