Spring 2021 – Archives

| Expand All | Collapse All |

| Department News |

View2020-2021 Digital History Lab Annual Report

In Summer 2020, the lab created and edited the blog, Teaching History Online. This blog contains posts by educators and students about their experiences during remote instruction in the Spring 2020 term. It is designed as a resource for teachers at all levels as they continue to be ready for online or hybrid instruction. DHL staff assisted several faculty members and graduate students implementing digital tools into their teaching. The directors worked with students and Professor Katherine Turk in HIST 179H, “Women in the History of UNC Chapel Hill” on the creation of a map and podcast to accompany their digital exhibition, “Climbing the Hill: Women in the History of UNC.” The DHL also continued their support of Dr. John Sweet’s “Historic Chapel Hill” project and collaborated with Dr. Daniel Cobb and his undergraduate research team on a story-map, “More Than a Trip,” documenting the travels of Native American author D’Arcy McNickle. The DHL continued and finished its work on its inaugural podcast, The Lens: Historians and Popular Media. The lab produced eleven total episodes of The Lens. The DHL has also launched its new podcast, “The Cutting Room Floor,” which allows historians to share engaging, entertaining, or even puzzling stories found during research that did not make the cut for larger projects. Episodes are produced with professional recording quality and an immersive audio experience. The DHL also redesigned the History Department Website. Emma Rothberg and Craig Gill worked in consultation with faculty to make sure all pages were accurate, inviting, and accessible. Part of this website update project was the creation of a History of the Department timeline, by Joshua Michael O’Brien (Class of 2022). The Digital History Lab organized several events for undergraduates, graduate students, and faculty across the university in the academic year. Over Summer 2020, Gabriel Moss held two short, introductory courses to GIS. In these hands-on, online workshops each participant produced an original mapping project and shared it with other participants. In total, the courses taught fifteen graduate students in multiple departments the fundamentals of Google Earth, QGIS, and ArcGIS Online. Everyone who participated was greatly supportive and enthusiastic about the class, and plans are underway for continued courses in historical GIS in the next academic year. In Fall 2020, the lab also hosted two major workshops. The first, in coordination with Wilson Library staff, discussed the classroom and personal uses of Omeka, a free, flexible, and open-source web-publishing platform for the display of library, museum, archives, and scholarly collections. The second was led by Craig Gill and focused on Zotero as a research resource and a bibliography database. These workshops focused on exposing faculty and students to new technologies and ways to use them in their teaching and research. Both workshops provided easy-to-follow tutorials and recordings were made available to those who could not attend the live webinar. The DHL started its Working Group in Fall 2020. Meeting roughly every two weeks, the Working Group was both a resource and a workshop for those in who are interested in learning more about and collaborating on digital humanities projects. The DHL Working Group had consistent attendance by both faculty and graduate student members. Meetings in the Fall consisted of short technology tutorials, while meetings in the Spring focused on sharing and getting feedback on personal digital humanities projects. Finally, the DHL has major plans for Fall 2021. We plan to host a workshop on “Podcasting for the Classroom,” which will be led by Ash Curry (Class of 2022). The DHL will continue to record and produce episodes of “The Cutting Room Floor” as well as hold workshops and Transcribe-A-Thons as COVID-19 protocols allow. The DHL has also begun plans for a Triangle public and digital history website that will showcase the work being done by faculty, students, and community partners. As a first step, the DHL created a blog page on our website where UNC students and faculty can share and discuss completed and ongoing digital projects. The DHL was co-directed by Emma Rothberg, Craig Gill for 2020-2021. Ash Curry was an invaluable contributor as an undergraduate research assistant and podcast guru. Gabriel Moss was an indispensable consultant to the lab. Thanks for reading! Emma Rothberg and Craig Gill Writing and Researching an MA Thesis in the COVID era In March 2020, Kaela Thuney was in the middle of her second semester as a graduate student, and beginning to develop plans for her MA thesis. She hoped to spend her summer break at the National Archives in Senegal, looking into the themes she planned to explore in her work: the slave trade, empire, and gender in nineteenth-century West Africa. “I thought if I could just go over and find some document no one had ever worked with before, I could tie all of those things together in this incredible and cutting-edge way,” she said. Marlon Londoño had received an award from the Institute for the Study of the Americas at UNC and was beginning to plan his visit to the Colombian national archives in Bogotá. Traveling to Colombia, he believed, was the necessary first step towards completing his project, which focused on soldiers’ experiences of the Thousand Days’ War between 1899 and 1902. “I wasn’t sure what to expect,” he recalled, “but I knew that I was going to go to Colombia, and that this would be the first and most important step.” Even as UNCChapel Hill shifted to online instruction and governments across the world began closing their borders, Thuney tried to remain optimistic. “I remember thinking, ‘Oh, we’ll shut down for two weeks, and then I’ll be able to continue on to West Africa for the summer,” she said. In the end, however, Thuney, Londoño, and the other members of their cohort would research, write, and defend their MA theses mostly at home. The coronavirus pandemic has required all students, faculty, and staff to adapt to new methods of working, studying, researching, and teaching. Archive and library closures, travel restrictions, and administrative uncertainty particularly affected graduate students who planned to research and write their MA theses in 2020. These students, who had little time to develop and complete their projects to begin with, often had to find new source bases, reconsider their methodology, and reformulate their arguments. Furthermore, the summer of 2020 would have provided many of them with their first opportunity to conduct archival research and work directly with historical documents.  The pandemic did not present a dramatic disruption in Pasuth Thothaveesansuk’s research plans. Although he initially planned to conduct research in the US National Archives and the Nixon Presidential Library, and also considered applying for a visa to visit the Political Archives of the German Foreign Office, he found that he was able to draw on the information available in published collections and online archives. As he noted, his global history project, examining West GermanChinese relations between 1968 and 1972, was ironically well-suited to a period of restricted travel. However, Thothaveesansuk was hardly unaffected by the restrictions associated with the pandemic. He defended his thesis at 2 AM local time while under mandatory hotel quarantine in Thailand, where he had returned to visit his family. “At least I got a good pandemic story out of it,” he said. For both Thuney and Callihan, conducting research during the coronavirus pandemic meant narrowing their focus. Thuney took a microhistorical approach, using Emory University’s Voyages Database to identify a French slave-trading ship intercepted by the British Navy in 1830, which she traced through records available in French and British online archives. Through the example of this individual ship, she examined issues of slavery, abolition, and forced labor in the emerging nineteenth-century imperial order. Callihan jettisoned his initial plan to add a comparative dimension to his project. Paradoxically, he said, focusing on Cologne itself made him more aware of the transnational networks in which the local Protestant community was embedded. In his dissertation, he intends to investigate the political dimensions of these religious networks and the challenges they posed to the consolidation of absolutist states.  For some students, this experience provided them with a new perspective on the process of historical research. For Londoño, conducting research online revealed that there were many possible ways of doing history. “I felt really insecure about myself as a researcher and as a scholar and graduate student because I hadn’t gone into the archive in person,” he said. But after completing his project and discussing his experience with professors and fellow students, he came to realize that the work he did from his kitchen table was no less authentic than the work he would have done at the archive in Bogotá. Similarly, Thuney was occasionally frustrated at her dependence on online resources and the Interlibrary Loan system, wishing that she had the opportunity to examine less commonly used physical sources located in the archives in Senegal. However, this experience demonstrated to her the importance of flexibility and creativity in the research process. “Nothing went the way I wanted it to this year, but I stayed the course best I could, and got something done,” she said. These four students, as well as the other members of their cohort, completed their projects successfully under very difficult circumstances — while also dealing with the other disruptions, disturbances, and stresses of the pandemic. Reflection from John A. Britton ’65 on time at Carolina and motivation for recent gift to support student research in the department of history Britton, a Professor Emeritus of Latin American History at Francis Marion University who majored in history at UNC, attributes his success at the university to a scholarship he received while on campus, covering one third of his tuition. Calling the financial assistance “a very positive factor in my persistence at the University,” Britton has always wanted to give something back to Carolina. “For the last fifty years, I have thought about reimbursing the University for the amount of money that the scholarship provided to me.” When asked about his motivation for making this commitment to current students, Dr. Britton had an immediate response: “I think one of the serious problems in higher education today is a lack of emphasis on the humanities and the relevant social sciences in trying to deal with social and political problems, and in understanding how media play a role in dividing our nation.” While underscoring the “captivating” academic experiences he enjoyed in the classroom, Britton is also eager to “convey an aspect of academic life at Chapel Hill that most people don’t even think about,” namely, his three years clearing the tables of wealthier classmates at Lenoir Dining Hall to pay for tuition. Although his grandfather attended UNC briefly from 1860-1861, Britton lacked the family support and personal connections that he says many of his classmates enjoyed. As a graduate of a rural high school with 100 students, he had not taken many of the rigorous math and science courses that more privileged students from preparatory schools or large high schools in Charlotte and Winston-Salem were able to bypass in their first year. “I worked part time as a bus boy in Lenoir Hall,” Britton recalls, “which meant that I cleared tables after people had eaten and carried a trayload of dirty dishes to the old conveyor belt.” Unsurprisingly for the early 1960s, racism and segregation pervaded the UNC campus, and Lenoir Hall furnished no exception. While less affluent White students worked as bus boys in the main dining hall, employees of color were forced to remain in the kitchen. Britton recalls gratefully that the hustle and bustle of the dining hall afforded him some opportunity, however limited, to interact with his non-White colleagues. “During rush hour, the administration would send African Americans from the kitchen to help pick up the dishes. It was a temporarily integrated workforce, and quickly the old lines of separation would dissipate. We were able to talk.” Britton remembers the early 1960s as an exciting time to be a student on campus: Radicalism was in the air. Fidel Castro’s name frequently came up in an upper division course on Latin America he took with Professor Lee Woodward. Britton recalls the Speaker Ban Law prohibiting communists from giving talks on campus during his sophomore year. Though Britton attributes his later scholarly interest in the Mexican Revolution to these and other events, he insists that the life lessons he learned as a bus boy were just as important. “About a third of the bus boys were graduate students in philosophy, sociology, and library science. There were men in their mid-20s; some were 40 and some were veterans.” Interacting with these older graduate students “was like taking another course.” Britton fondly remembers the “informal, unstructured discussions with these older fellows who were very frank: They didn’t hold anything back. They leveled devastating critiques of their professors, which I later found out stemmed from frustration over their high standards and the pressure to do a good job.” He counts this “transformative experience that would never show up on a resume” as one of the highlights of his UNC experience. “I was fortunate to meet people who could be frank with you.” Britton is grateful for the lessons, intellectual and otherwise, he learned at UNC, and the department of history is grateful for his generosity toward today’s students. Building Renaming Marks Reckoning with Racism in UNC’s Past On July 9, 2020, the academic units housed at 102 Emerson Drive—the Departments of History, Political Science, and Sociology, and the Curriculum on Peace, War, and Defense–submitted a request to UNC’s Commission on History, Race and a Way Forward to rename Hamilton Hall as Pauli Murray Hall. A poet, lawyer, writer, activist, priest, professor and intellectual whose work inspired several generations of cultural, political and social figures, Murray’s commitment to critical thinking, creativity, historical research, and above all to justice, epitomizes the ideals that the UNC History Department believes the historical profession should uphold. The department’s faculty, students and staff are committed to ensuring that the work taking place in Pauli Murray Hall reflects the remarkable legacy of this important luminary. Department chair Professor Lisa Lindsay, an early advocate for renaming the building, emphasizes the contrast between Murray–whose legal research was foundational both for Thurgood Marshall’s challenge to “separate but equal” and for Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s challenge to job segregation by sex–and Hamilton, whose research was shaped by and contributed to white supremacy. As Lindsay explains: “It is fitting that we replace the one name with the other, because both reflect linkages between historical scholarship and public citizenship–one in a way we repudiate and another in a way we hope to emulate.” Murray’s own experience of discrimination here on campus closely illustrates the connection between the research conducted at UNC and the broader mission of the university. When she applied to Carolina for graduate studies in sociology in 1938, she was denied admission on the basis of her race despite her impeccable credentials. Murray’s personal rejection came from none other than UNC President Frank Porter Graham. Then, in 1978, she was offered an honorary degree from UNC, which she turned down because North Carolina was at that time tied up in a legal case in which it was resisting desegregation in all parts of the state university system. “In these two instances,” Lindsay explains, “if not for official racism, Pauli Murray would be both an alumna of UNC (from a department now housed in the building we hope to name after her) and the holder of an honorary degree from the university.” Despite her application’s rejection from UNC, Murray earned advanced degrees, including a PhD, in law. Her research underwrote the legal tactic that Thurgood Marshall used in Brown v. Board, and she co-authored the arguments in Reed v. Reed, a case argued by Ruth Bader Ginsburg that overturned sex discrimination in estate disputes. Later in her life, she was ordained as a minister, preaching her first service at the Episcopal Chapel of the Cross near UNC’s campus. The renaming decision also rests on lesser known connections between Murray and the university that can be unearthed in her writings. Published posthumously in 1987, Murray’s memoir, Song in a Weary Throat, won the Robert F. Kennedy and Lillian Smith Book Awards, among numerous other distinctions. Praised as “visionary” by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., and upheld as “a model for a new understanding of the pursuit of social justice” by Drew Gilpin Faust, Song in a Weary Throat also underscores the strong connection between Chapel Hill and the author’s personal and family history. The first such connection is that Murray’s maternal grandmother, Cornelia Smith, was the daughter of an enslaved black woman whom Pauli describes as “part-Cherokee” who was sexually assaulted by a plantation owner/lawyer named Sidney Smith. Cornelia was born in the 1840s and she married Pauli’s grandfather in 1869. The white Smiths owned extensive plantation lands in southern Orange County and northern Chatham County; and a big Smith house still stands on Smith Level Road, a thoroughfare which leads from Carrboro to North Chatham County that is well known to everyone on campus. Second, as a child growing up in Durham, Murray met Julian Carr, shortly after he dedicated UNC’s (now removed) Confederate “Silent Sam” Statue with a speech whose violent racism has earned Carr notoriety in the annals of Chapel Hill history. The meeting took place because Murray became an avid reader while living with an aunt in Durham. By the age of ten, she had read so many books at the “Colored Durham Library” that she received a prize. As Murray recounts in her memoir: “One year I won first prize among the colored children for having read the most books in the library. The prize, a fountain pen, was presented to me by General Julian S. Carr, a man my folks called a ‘true southern aristocrat.’ The presentation ceremony and General Carr’s words of praise made me feel very proud of my achievement.” Commenting on the irony of this award coming from an avowed defender of the Confederacy, Professor Lloyd Kramer notes “the strangeness of history: The man who spoke so belligerently about white supremacy and the Confederacy at the dedication of Silent Sam later gave a pen to Pauli Murray to honor her reading achievements at a ceremony in Durham.” Carr could not then have imagined that the gifted child before him would play a pivotal role in creating a new landscape that would eventually make the removal of the “Silent Sam” statue possible (albeit with much difficulty) in 2019. Kramer continues: “She took that ‘pen’ (if I may speak metaphorically here) and went on to write her own story and to challenge the racist system and University policies that Carr had so strongly defended. Little did he know that he was giving a pen to someone who would assault—with lifelong determination–the whole racist system he sought to defend.” The community of faculty, students and staff in Pauli Murray Hall views the process of renaming the building not as an end in itself, but as the beginning of the significant work that remains to be done on campus in achieving Murray’s vision of a just and fair society, whose contours are so brilliantly captured in the concluding lines of her poem, “Prophecy”: I have been cast aside, but I sparkle in the darkness. Working Group on Equity and Inclusion Hosts “Courageous Conversations about Race in the Academy: A Roundtable with UNC History PhDs”This Spring semester, the department’s Working Group on Equity and Inclusion hosted a virtual roundtable featuring six alumni from the Ph.D. program who all engage in diversity, equity and inclusion work in their scholarship, teaching and service. The panel featured Jessica Dixon-McKnight (Assistant Professor at Winthrop University), Bonnie Lucero (Associate Professor at the University of Houston), Julie Reed (Associate Professor at Pennsylvania State University), Devyn Spence Benson (Chair and Associate Professor of Africana Studies at Davidson College), Carlton Wilson (Dean of the College of Arts, Sciences and Humanities at North Carolina Central University), and Brandon Winford (Associate Professor at The University of Tennessee, Knoxville). The event took place on March 23, and was open to all students, faculty and staff in the UNC History department.

The roundtable provided an open space for panelists to talk about their experiences as Black, Indigenous and other People of Color in academia. A common theme was the need to find a supportive community, which proved critical in helping them navigate the difficulties of the academy, whether as graduate students or professional historians. These positive relationships to family members, friends and mentors helped them combat the sense of loneliness and isolation they felt throughout their studies. In particular, Julie Reed highlighted the American Indian and Indigenous Studies program at UNC where she found a supportive community consisting not only of professors such as Theda Perdue and Kathleen DuVal, but also of First Nations graduate students in other departments. Panelists also commented on the importance of having a strong sense of self. Winford remarked on the need to separate one’s identity from work because “academia forces you to set aside who you are to meet some expectation.” Along a similar vein, Benson reminded the audience, predominantly composed of graduate students, that meritocracy is often illusory and that many factors outside their control go into decisions regarding hiring, grants and awards. All panelists encouraged current graduate students to not doubt the worth of their work and their own selves as they continue their journeys in the history profession. The roundtable was organized by the department’s Working Group on Equity and Inclusion, which includes professors Genna Rae McNeil, Malinda Maynor Lowery, Susan Pennybacker and Miguel La Serna, graduate students Patricia Dawson, Cristian Walk and Laura Woods, and staff member Jennifer Parker. Following the event, I interviewed Professor Miguel La Serna, who moderated of the roundtable. La Serna expressed his gratitude to the panelists for their willingness to come back and speak candidly to the Carolina community because these are “the conversations that we really need to be having right now. They’re difficult to have, but they ultimately become really enlightening.” Additionally, the alumni roundtable was a step in building a greater community and a greater support network for underrepresented people who come from diverse backgrounds in the History department. The Working Group on Equity and Inclusion resulted from the initiative of several faculty who wanted to start a meaningful dialogue about issues of equity, diversity and inclusion and anti-racism within the History department, curriculum and degree programs. Prior to the formation of the Working Group in the Fall 2020, the responsibility and burden of this work had fallen upon graduate students and several faculty members on an ad hoc basis. The establishment of this Working Group represents the department’s direct recognition of the fact that the work to identify and dismantle structural issues requires more deliberate, organized and concerted efforts. The Working Group has issued multiple statements responding to real world events and developments, and for most of this academic year, it has focused on identifying areas for growth and improvement in the department. These findings, obtained through the collection of data on the department and university level and through the peer-reviewed research, will inform strategic plans, both short-term and long-term, to start making strides in these areas. Six History Majors Successfully Complete Senior Honors Theses

This year’s Honors students worked on an impressive range of projects which relate not only to the field of U.S. history, but also to modern European, South African, colonial and gender history. Patrick Clinch and Flannery Fitch worked on nineteenth-century U.S. history. Clinch investigated how the life and career of P.T. Barnum, exemplified through his popular human exhibits, reflected and influenced the racial politics of the Reconstruction Era. Fitch offered a comparative analysis of the diaries of two female spies on opposite sides of the American Civil War. Josh Howard’s and Kasha Seltzer’s theses focus on two important developments of the U.S. twentieth century. Howard researched evangelism and identity in the Orthodox Church in the U.S., while Seltzer’s work unpacks the social, political and institutional consequences of ABSCAM, an FBI investigation in the late 1970s that led to the conviction of six members of the House of Representatives and a senator. Kimathi Muiruri and Jona Boçari, coincidentally the cohort’s only international students, worked on South African history and Italian history respectively. Muiruri analyzed the livelihood and political strategies of African migrant laborers in Durban from 1874 to 1906. Boçari’s work explores the intersection of gender, memory and politics in post-1945 Italy by focusing on the analysis of four autobiographical accounts. Kimathi Muiruri and Kasha Seltzer shared with me their experiences conducting research and writing an Honors thesis in an academic year as tumultuous as 2020-21. The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted both their plans to conduct research over the summer. Seltzer said that her initial topic idea was to focus on the one person, Senator Harrison Williams Jr., and to consult archive papers held at Rutgers University in New Jersey. Because she was unable to go on her research trip, Seltzer had to pivot to working with any digitized documents that were available online. This challenge forced Seltzer to modify her topic, which was discouraging at first but proved far more enjoyable for her later on. Similarly, Muiruri’s plans to travel were also disrupted by the pandemic, causing him to lose access to many sources and to work with online sources instead. For Seltzer, Muiruri and their cohort peers, the ability to think creatively around these challenges proved essential to their work. These strategies included relying on the UNC Library and the loan system, HathiTrust temporary access, digitized primary sources and purchasing books whenever unavoidable and necessary. Beyond the limited access to primary sources, the remote-learning environment placed an additional burden on the students working on their honors theses. “The fatigue of Zoom classes was worse than previous years of in-person class — no moving around throughout the day, no punctuation with natural breaks, and little social interaction made work exhausting,” Muiruri stated. Seltzer added that the lack of in-person support and limited opportunities to connect with other thesis classmates made this endeavor especially hard. The support provided by faculty advisors helped mitigate some of these challenges. For Muiruri, working with his advisor, Dr. Lauren Jarvis, was one of the best parts: “Her approval and criticisms let me know when I was on the right track and how I could get better. Without that guiding light I would have been overwhelmed.” Despite the challenges and the toll of isolation and a public health crisis, the experience of starting and finishing an Honors thesis proved extremely rewarding. Seltzer added that she greatly appreciated the opportunity to meticulously research a fascinating topic and the autonomy over the entirety of her project. The successful defense of her year-long work in front of a committee of faculty members was, for Seltzer, “the best feeling. It made it all worth it, because I knew that all my time had been spent in doing good work.” History majors who complete senior Honors theses showcase their work in the department’s Honors Symposium. This year’s Symposium was held virtually on May 6, 2021 and featured two panels: Conflict Within and Without, and Cultural Adaptations and Resistances. While the Symposium is always an opportunity to celebrate the accomplishments of the thesis writers, this year’s Symposium was especially meaningful not just because of the pandemic’s challenges, but mainly because of the determination, creativity and fortitude that we all have shown. |

| Faculty Spotlight |

ViewHistory Seminar Fosters Global Collaborations over Zoom

For four weeks, the HIST 783 seminar met with nearly 15 students and faculty from King’s College and Charles University in Prague. Participants discussed common readings, engaged in lively discussions, and benefited from the guidance of experts such as KCL’s James Bjork and Ota Konrád at Charles University. The class also nominated and voted on readings in an article prize contest, during which students reviewed a number of scholarly works in the field of Russian and Eastern European history. This allowed students a chance to read articles they might not have otherwise encountered, to consider the most salient factors behind a given nomination, and to compare and contrast the topics, methodologies, and arguments of each piece. This part of the course, meant to introduce new scholarly literature and hone students’ skills at crafting or critiquing arguments, also brought to the fore a few key differences between students’ respective academic environments, including language differences, funding issues, research questions, and one’s “proximity” to a given topic. The group converged around a love and deep appreciation for the field, a desire for more cross-cultural contact, and, in some cases, even similarities in participants’ research topics. These networks demonstrate the value of COIL in forging new ties between scholars and universities. Though some participants may never visit the home universities or countries of their new Transatlantic colleagues, this is of secondary importance to what Professor Bryant considers to be the real strength of COIL seminars: the ability to experience how people in another part of the world live, what histories these places may have, and how perspectives on key issues may vary depending on one’s academic environment or closeness to a topic or location. Having had a year or more to practice, students came to class prepared and well acquainted with online functions or “Zoom etiquette,” thereby allowing conversations to develop organically without technical difficulties or confusion. In fact, Professor Bryant argues that such a model might not have “occurred to [him] in the pre-pandemic era,” when virtual functions were relatively marginal outside of hybrid or online courses. Now, however, virtual components are integrated into all aspects of learning, thereby facilitating otherwise difficult meetings and seminars like these. The ease with which transnational scholarly networks have expanded thanks to online modalities leads many to hope that a virtual component will remain after the pandemic, especially for large professional and organizational conferences and seminars. While Professor Bryant hopes to teach this course in-person next time he offers it, he is confident that a Zoom-based COIL component will remain part of the experience. Global scholarly networks and exchanges, such as those that took place in Professor Bryant’s class, are crucial to the health and rigor of a field. COIL’s popularity and success underscores the vitality of UNC’s global connections as well as the university’s commitment to scholarly excellence. |

| Alumni Spotlight |

ViewBailey White ’16 Founds Mentorship Group

A Senior Consultant at Deloitte Consulting, Bailey studied History and Business Administration at UNC. Originally from Winston-Salem and a lifelong Tar Heel fan, he became a history major after taking a course on the History of North Carolina with Professor Harry Watson. The course strengthened a passion for historical research stretching back to his AP history days. Bailey’s professional success in Deloitte’s Government and Public Services (GPS) practice might, at first glance, seem to stem primarily from his training in business. Yet he attributes much of his success in the job market and at work to his background in history. Since beginning his career at Deloitte, Bailey has noted the ways in which the study of history has informed and enhanced his effectiveness with clients. For instance, Bailey’s role as a consultant requires him to analyze, synthesize, and collate data, and then distill this data into an “argument” that he must convey to his government clients in a succinct but engaging way. This can only be achieved, he notes, by writing clearly and effectively, by considering counterexamples and limitations to one’s argument, and by thinking critically. Bailey’s engagement with specific federal, state, and local policies, moreover, is bolstered by his knowledge of the historical context in which those policies came into being. Bailey’s firm belief that students with history degrees can find relevant and rewarding work outside of academia led him to establish the Department of History Career Mentors Coalition (CMC) at UNC. According to its mission statement, CMC prepares history majors for “their next chapter.” This non-profit group of volunteers allows students to engage with alumni of the department, as well as faculty members, to develop their resumés and interview skills, to introduce students in the department to careers that might not seem like obvious paths for a history major (but, in fact, are), and to provide historically trained job seekers a general understanding of the skills they will need to succeed in the job market in specific lines of work. Though only a year old, this organization has attracted widespread support from alumni and current faculty members. As many of the careers and industries represented within the CMC are not usually apparent to most history majors, the organization continues to seek alumni and faculty willing to share their expertise and to mentor our undergraduates. This service is free to all UNC students, and the CMC plans to hold in-person seminars following the reopening of campus. Bailey’s work on and off campus shows how valuable a history degree, especially from UNC, can truly be. For more information, contact bawhite@deloitte.com |

| History in Our World |

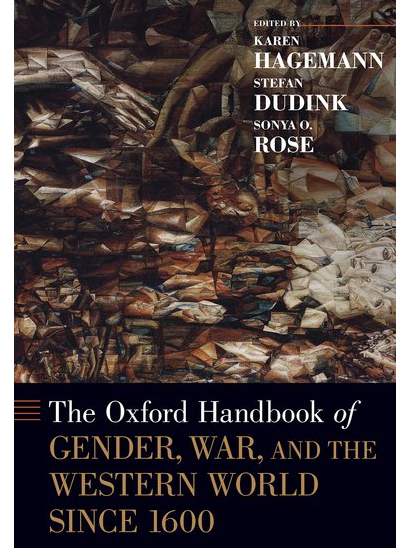

ViewSpotlight on Scholarship: Historicizing Gender, War and the Military

The publication of the Oxford Handbook was launched on March 5, 2021, in a virtual transatlantic roundtable on gender, war and citizenship, held also in memory of Sonya O. Rose, who passed away a few weeks before the book was published. The roundtable featured several of the handbook authors, who all discussed aspects of wartime politics of citizenship in various historical and geographical contexts. The roundtable convened members from the American Academy Berlin, the Netherlands Institute for Advanced Studies, and the center for Gender and Diversity Studies at the Radbound University Nijmegen. Along with the Department of History and the Curriculum in Peace, War and Defense at UNC-Chapel Hill, these four institutions generously sponsored the work on the handbook. The Oxford Handbook marks an important contribution to a field that has disregarded gender and focused predominantly on men. Its innovative approach and structure also distinguish it from many works by scholars who have focused exclusively on women. “The handbook emphatically takes gender to refer to both men and women, along with the related constructions of femininity and masculinity. In doing so, it avoids the implicit assumption guiding much of the existing literature that only women’s relation to the military and war requires an explanation, a way of thinking that regards men’s place in the military and war as somehow self-evident and not in need of explanation,” Hagemann stated in the roundtable. This work then offers tremendous insight on how concepts of gender, war and violence need to be understood as relational and historicized appropriately and deliberately. A second major strength of this volume is the wide temporal and geographical ground covered in the essays. Starting from the Thirty Years’ War and ending with post-Cold War era, the chapters of the handbook focus not on specific countries, but on historical processes which allow for comparative and temporal analyses of gender and war over time. The handbook moves beyond the conventional history-writing frameworks of nation states and the West. “The Western world,” Hagemann remarked, “is both a changing and contested construct and a historical phenomenon which was transformed through colonial and imperial expansion.” The handbook, therefore, critically engages with developments in colonial and global history as well. The publication of the Oxford Handbook is supplemented by Gender & War Online, a digital humanities and public history project based at UNC-Chapel Hill. Gender & War Online offers extended bibliographies for all chapters, as well as nearly 9,000 annotated bibliographical entries with information on secondary literature, autobiographical accounts, primary source websites and films on the subject of gender and war. As of April 2021, the website has had more than 200,000 visits. The symbiotic accompaniment of Gender & War to the Oxford Handbook marks another aspect of this work’s innovative approach. Taken together, these two resources seek to make the extensive research in the field of gender and war available to a broader audience, including teachers, students, and researchers. The integration of digital humanities in Professor Hagemann’s work reflects the broader commitment of the faculty in the UNC History department to making history accessible beyond the limits of the classroom. |

| Out of the Archives |

ViewThe History of Pauli Murray Hall UNC-Chapel Hill administrators first applied for funding to establish a new building for departments in the Social Sciences Division — including History, Political Science, Anthropology, and Philosophy — in 1966. These disciplines, they wrote, were growing especially quickly. The four departments required a large building with the capacity to expand in future decades. This new Social Sciences Building was one of the most important parts of an ambitious project of construction and renovation. Having not received all the funds that they requested, architects and administrators reshuffled the departments to be housed in the new building and decreased the amount of space provided for classrooms and offices. In 1969, the History, Sociology, and Political Science chairs wrote a letter to protest the new plan, which they argued left their departments with less room than others enjoyed. Furthermore, the university had failed to include them in the planning process, disregarding the needs of their faculty, students, and staff. Despite the chairs’ objections, work began on the new Social Sciences Building in 1971, continuing throughout the following semesters. Planners and construction workers took care not to disturb an old oak tree growing behind the building when installing pipes and electrical wires. Residents of a nearby dorm, however, complained that the noise prevented them from studying. Two attempted unsuccessfully to have their dorm fees partially refunded after moving off campus. The construction site also drew Jesse Jackson’s attention when visiting UNC-Chapel Hill in the spring of 1972. He pointed to it when calling for measures to ensure that Black companies and workers could benefit from state contracts, declaring that the university had both an economic and an educational responsibility to Black North Carolinians. According to an article in the Daily Tar Heel, the new building was not quite complete when the three departments moved in at the beginning of fall 1972. Classrooms lacked tables and chairs, and offices were not equipped with telephones or bookshelves. The elevators proved to be an enduring problem. In 1975, History Department chair George Taylor placed a sign on the fifth floor urging students to consider taking the stairs. While each individual was “at liberty to choose his own mode of vertical movement,” the elevators had an alarming tendency to drop without warning. Other history professors complained that they took too long to arrive. Some years later, a student saw a conspiracy behind the building’s elevator delays, suspecting that they were programmed to return to the top floors for the convenience of the faculty. The elevators’ renovation in 1990 is commemorated by a small gold plaque dedicated to Samuel Williamson — a decades-old inside joke. As Professor Harry Watson explained, the building’s faculty used to say that Williamson, the Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences and university provost during the 1970s and 1980s, had bought their support with promises for new elevators. Malfunctioning elevators remain among the chief complaints of members of the History Department, nearly all of whom have stories about peering into empty elevator shafts or informing the uninitiated, day after day, that the light behind the fifth-floor button does not work. Conservative traditionalists among the university’s leaders had always been suspicious of modern architecture, despite Director of Planning Arthur Tuttle’s insistence that new elements be designed to fit harmoniously with existing structures and environments. The Social Sciences Building was designed by Cameron, Lee, and Associates (later Little, Lee, and Associates), a Charlotte firm also responsible for the Student Union, Student Stores, Undergraduate Library, and Greenlaw Hall, as well as a number of other concrete landmarks around North Carolina. These structures share a bold, unpretentious, unadorned style typical of public institutions built during the decades after the Second World War — high modernist faith in rational planning to improve mass society, rendered in concrete. Modern architecture, one student declared in 1957, “symbolizes the philosophy and the needs of today.” By the 1970s, however, the public was becoming far more skeptical of this philosophy. Although architects attempted to adapt modernist forms to the campus’s aesthetic and practical requirements, it did not take long for the student body to come to a clear consensus: the new building was “just plain ugly.” It was a short step from ugly to oppressive. Despite the rumors, there is no evidence that modernist buildings at UNC-Chapel Hill — or anywhere else in the country — were built with campus unrest in mind. Modernist architects’ utopian plans to make education accessible to ordinary citizens had been reinterpreted as dystopian schemes to control them. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, the university turned its attention to the needs of disabled students for the first time, spurred by federal and state legislation as well as by campus organizing and advocacy. The Social Sciences Building was one of the first buildings at UNC-Chapel Hill to be planned with ramps for wheelchair access, as one activist noted shortly after it was built. University planners modified buildings for increased accessibility throughout the 1970s, adding curb cuts, elevators, ramps, and handrails. As current history graduate student Dalvin Tsay explained, however, accessibility has come to mean more than simply the ability to get in the door: “You can tell that the architects in a newer building like FedEx considered the entire experience, while in the 1970s, it was just a matter of putting in a ramp or an automatic door.” As a manual wheelchair user, he finds it particularly frustrating to scale the steep ramps to the entrance, especially when hauling a backpack full of books. The Social Sciences Building received the name Hamilton Hall without input from the broader public. In a satirical article, a writer for the Daily Tar Heel lampooned the bureaucratic process, describing an imaginary professor’s objections at a meeting of the equally imaginary Faculty Committee for Imposing Edifices: “A member of the History Department pointed out that James G. de Roulhac Hamilton was a follower of William A. Dunning and that the Dunning School was best known for its anti-Negro view of Reconstruction. He claimed that the theories of Dunning and Hamilton had been discredited . . . Everyone agreed that Hamilton Hall was the best name for the new building.” The chairs of the History, Sociology, Political Science, and PWAD departments cited this article in their July 2020 letter to the Chancellor calling for the building to be renamed, pointing out that Hamilton’s interpretation of history was already widely challenged on campus at the time the building was finished. Renaming the building after Pauli Murray, as Professor William Sturkey said, honors a scholar whose work in the service of justice has stood the test of time. It also asserts the rights of students, faculty, and staff to define and shape their physical environment. The story of Pauli Murray Hall as a physical space has often been one of bureaucratic disregard. But the building is also the product of an era of optimism, confidence, and change in our field and at the university. Considering the legacy of Pauli Murray herself, as well as the history of the building now named after her, provide an opportunity to imagine what should be changed and what preserved to make the department more responsive to the aspirations and needs of those who work and study there. Thanks to Jason Tomberlin and Matthew Turi from University Libraries for their assistance in locating and scanning documents and other resources. Lyric Grimes provided invaluable assistance and information for this article. |

| Graduate Student News |

ViewUpdate from Professor Sarah Shields, Director of Graduate Studies Despite these difficult conditions, the graduate students continued to pursue and disseminate their research. Donny Santacaterina and Laura Cox organized the spring Department Research Colloquium, at which Mark Reeves and Francesca Langer presented their research, and Professor Cynthia Radding offered comment. Graduate students also participated in the many committees behind the smooth running of the department, including the Committee on Teaching, the Graduate Studies Committee, the recent search committee, and the new Diversity, Equity and Inclusion working group. Despite the challenges of this academic year, eleven graduate students earned their Ph.Ds. We celebrated their achievements, and those of our new M.A.s, with a virtual recognition ceremony. Our featured speaker, Jacquelyn Hall, talked about becoming a historian and about the remarkable changes in this department since she first arrived in the 1970s. If you’d like to hear it, go to the new department YouTube site administered by our own Digital History Lab. We wish our graduates all the best: Turgay Akbaba, Alyssa Bowen, Robin Buller, Brian Fennessy, Lucas Kelley, Aubrey Lauersdorf, Max Lazar, Daniel Morgan, Virginia Olmsted McGraw, Mark Reeves, and Daniela Weiner. To see the remarkable accomplishments of our current graduate students and alumni this year, make sure to look at the upcoming Annual Report, which will be posted online in the coming months. The Graduate Program is in the midst of some significant changes as we grapple with both the decrease in funding from the University and the new landscape of demands for Ph.D. historians. While taking a year out from admitting new students so we could make sure we could adequately fund our own, we have been assessing our needs and revising our program. We envision a renewed program combining curricular innovation with our long-standing emphases on rigorous scholarship and broad historical education. |

| Undergrad News |

ViewUndergraduate News Independently from the Frank Ryan Prize, Kimathi Muiruri was also awarded the History department’s Cazel Prize, part of the Chancellor’s prize ceremonies. The Cazel prize recognizes an outstanding graduating senior who has excelled in the study of history, contributed to the life of the History department, and shown a profound commitment to the values of the historical discipline on and off campus. For just one example of Kimathi’s activities beyond the classroom, see his short commentary in the Wall Street Journal that made a historically based, cogently written argument for reparations to African Americans. The department was equally pleased to award this year’s Joshua Meador prize for the best 398 “capstone” seminar essay. The winner was Sean Nguyen for his essay “A Forgotten Legacy: The Origins of Asian American Student Activism at the University of North Carolina,” written under the supervision of Professor William Sturkey. In this timely piece of historical research, Sean explores the attempt of Asian American UNC students to start an Asian Center on campus in the 1990s, demonstrating how a growing minority population at a Southern university fought for more inclusive cultural programs. (Not coincidently, UNC opened the doors to its new Asian American Center this year.) History also welcomed a new cohort of inductees into Phi Alpha Theta: Allison Holbrooks, Hunter Hetfeld, Caroline Henderson, Samuel Timmons, Julianne Gates, Diego Barrientos, Grace Taylor, Taylor Williams, John Reynolds, Colton Wood, Scott Grant, Katherine Leonard, Sean Thomas, Lauren Taylor, Olivia Bornkessel, Adam Tatum, Justin Evangelisto, Henry Johnson, Ashley Masi, and Barry Klug. Our congratulations go to them all. On the other hand, faculty and students continued to adjust and innovate as they faced the ongoing demands of remote teaching. For one stellar example of how faculty and students adapted to remote teaching, consider Professor Katie Turk’s research-intensive honors class, Climbing the Hill, which explored the history of women, sex, and gender right here on campus. The class originally planned to present its research outcomes in the form of a physical exhibition in the Wilson Library. COVID-19 disrupted those plans. Undeterred, Professor Turk and her students, with the help of the Special Collections staff and Digital History Lab, transformed their exhibition into a digital space: https://exhibits.lib.unc.edu/exhibits/show/womenatunc/introduction The class also prepared a digital map giving a virtual tour of campus sites related to women’s history and created a series of podcasts related to their research findings. Professor Turk and her students offer just one especially impressive example of how the undergraduate program in History has not just survived the coronavirus pandemic but thrived under its challenging circumstances. Nevertheless, faculty and students agree: there is no replacing face-to-face contact in the classroom. Here’s to hoping that 2021-22 finds us all back in the classroom, safe, healthy, and ready to pursue our historical studies. |

Gifts to the History Department

The History Department is a lively center for historical education and research. Although we are deeply committed to our mission as a public institution, our “margin of excellence” depends on generous private donations. At the present time, the department is particularly eager to improve the funding and fellowships for graduate students.

Your donations are used to send graduate students to professional conferences, support innovative student research, bring visiting speakers to campus, and expand other activities that enhance the department’s intellectual community.

|

To make a secure gift online, please click “Give Now” above.

The Department also receives tax-deductible donations through the Arts and Sciences Foundation at UNC-Chapel Hill. Please note in the “memo” section of your check that your gift is intended for the History Department. Donations should be sent to the following address:

UNC-Arts & Sciences Foundation

Buchan House

523 E. Franklin Street

Chapel Hill, NC 27514

Attention: Ronda Manuel

For more information about creating scholarships, fellowships, and professorships in the Department through a gift, pledge, or planned gift please contact Ronda Manuel, Associate Director of Development at the Arts and Sciences Foundation: ronda.manuel@unc.edu or (919) 962-7266.

The Digital History Lab’s second year has been a productive and rewarding one. With a staff of four, the DHL has continued one podcast and started another, offered tutorials and workshops, produced a weekly newsletter highlighting tools and events relevant to digital history, and conducted regular consultations as we continue to deal with the implications of teaching in the time of COVID-19.

The Digital History Lab’s second year has been a productive and rewarding one. With a staff of four, the DHL has continued one podcast and started another, offered tutorials and workshops, produced a weekly newsletter highlighting tools and events relevant to digital history, and conducted regular consultations as we continue to deal with the implications of teaching in the time of COVID-19.

The 2020-2021 academic year has presented unprecedented challenges, from a global pandemic to social turmoil, for faculty and students alike. Yet, despite these disruptions and disturbances, six History majors were able to successfully complete Senior Honors Theses. For most students this is the largest and most in-depth project they undertake in their college careers. The rigor of the Honors thesis program is demonstrated by students’ commitment to conducting original research to produce a paper that is, on average, 75 pages long. The students who embark on their thesis projects are supported by a faculty adviser and the instructor of the thesis two-course sequence, led this year by Professor Marcus Bull. This year’s thesis cohort is unique from cohorts of the past in that the exceptional challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic affected these projects from start to finish. Professor Bull remarked that the fact that these thesis students “confronted and dealt with these challenges does all of them great credit.”

The 2020-2021 academic year has presented unprecedented challenges, from a global pandemic to social turmoil, for faculty and students alike. Yet, despite these disruptions and disturbances, six History majors were able to successfully complete Senior Honors Theses. For most students this is the largest and most in-depth project they undertake in their college careers. The rigor of the Honors thesis program is demonstrated by students’ commitment to conducting original research to produce a paper that is, on average, 75 pages long. The students who embark on their thesis projects are supported by a faculty adviser and the instructor of the thesis two-course sequence, led this year by Professor Marcus Bull. This year’s thesis cohort is unique from cohorts of the past in that the exceptional challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic affected these projects from start to finish. Professor Bull remarked that the fact that these thesis students “confronted and dealt with these challenges does all of them great credit.” Zoom has opened up exciting possibilities for international collaborations in the History Department. This year, Professor Chad Bryant’s HIST 783 Colloquium on Russian and Eastern European History included a component the students in the course had not encountered before. As part of UNC’s COIL (Collaborative Online International Learning) initiative, Professor Bryant’s course was one of nearly 15 other courses throughout campus that capitalized on virtual learning by engaging in transnational seminars. Supported by the Chancellor’s Global Education Fund, the COIL initiative seeks to expand, reconfigure, or develop new methods of teaching as a commitment to pedagogical excellence among faculty and graduate students. Courses that qualify for COIL funding and aid engage in collaborative multi-week long modules with other universities, where students and faculty alike are given a chance to expand their global awareness, interact with like-minded scholars abroad, make scholarly connections, and, in the case of Professor Bryant’s course, compare and contrast methodologies or historical questions.

Zoom has opened up exciting possibilities for international collaborations in the History Department. This year, Professor Chad Bryant’s HIST 783 Colloquium on Russian and Eastern European History included a component the students in the course had not encountered before. As part of UNC’s COIL (Collaborative Online International Learning) initiative, Professor Bryant’s course was one of nearly 15 other courses throughout campus that capitalized on virtual learning by engaging in transnational seminars. Supported by the Chancellor’s Global Education Fund, the COIL initiative seeks to expand, reconfigure, or develop new methods of teaching as a commitment to pedagogical excellence among faculty and graduate students. Courses that qualify for COIL funding and aid engage in collaborative multi-week long modules with other universities, where students and faculty alike are given a chance to expand their global awareness, interact with like-minded scholars abroad, make scholarly connections, and, in the case of Professor Bryant’s course, compare and contrast methodologies or historical questions. Anyone considering a degree in history who has been asked the question, “What for?”, need only look up Bailey White ’16.

Anyone considering a degree in history who has been asked the question, “What for?”, need only look up Bailey White ’16. Faculty in the UNC History department have consistently produced scholarship that not only engages with timely issues, but can also offer new perspectives for understanding the historical developments of these issues in different contexts. A recent publication co-edited by professor Karen Hagemann, alongside Stefan Dudink and Sonya O. Rose, fits well within this tradition of innovative scholarship. Published in November 2020 by Oxford University Press, The Oxford Handbook of Gender, War and the Western World since 1600 is a collection of 32 essays which investigate the interplay of the social construction of gender and the shaping of warfare and military culture. The handbook features 28 distinguished scholars from 3 continents and 6 countries, who draw from the fields of gender and military history, and from the disciplines of cultural studies, political science and international relations.

Faculty in the UNC History department have consistently produced scholarship that not only engages with timely issues, but can also offer new perspectives for understanding the historical developments of these issues in different contexts. A recent publication co-edited by professor Karen Hagemann, alongside Stefan Dudink and Sonya O. Rose, fits well within this tradition of innovative scholarship. Published in November 2020 by Oxford University Press, The Oxford Handbook of Gender, War and the Western World since 1600 is a collection of 32 essays which investigate the interplay of the social construction of gender and the shaping of warfare and military culture. The handbook features 28 distinguished scholars from 3 continents and 6 countries, who draw from the fields of gender and military history, and from the disciplines of cultural studies, political science and international relations.