Spring 2018 – Archives

| Expand All | Collapse All |

| Department News |

ViewPhi Alpha Theta Hosts Quiz Bowl for Local High School StudentsThe Phi Alpha Theta High School History Quiz Bowl – UNC Phi Alpha Theta’s main annual event – is a history trivia competition for regional high schools held every spring. Organized by the History Quiz Bowl Committee, an undergraduate and graduate student organization comprised of PAT and non-PAT history and history-adjacent UNC students, who write and edit the questions, plan the matches, and organize and staff the event, the quiz bowl pits teams of 2 to 4 high school students against each other over ten matches to answer questions on diverse historical topics covering everything from the earliest human civilizations to current events. The two teams with the highest cumulative scores then face off in a heated final match to decide the winner.  This year, we were thrilled to host teams from East Chapel Hill High School and Durham School of the Arts. Ultimately, the 2018 UNC PAT High School History Quiz Bowl Trophy went home with East Chapel Hill, represented by Thomas Brodey, William Ke, and Angad Grewal, the defending 2017 champions.  –Chris LaMack, Phi Alpha Theta New Issue of Traces Hits the Newsstands

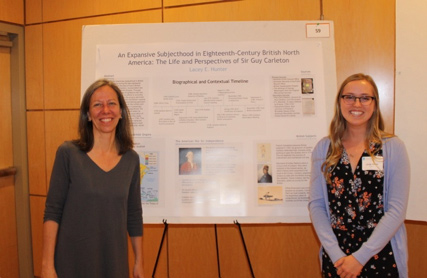

–Sarah Miles, graduate co-editor History Majors Present Original Research at Honors Symposium Jacob Bell, and Jeremy Howell discuss their Honors theses. At the symposium, honors thesis writers divided into three panels: Twentieth-Century World, Religious History, and Early Modern Empires. Each panelist gave a short presentation on their thesis, and attendees asked questions and offered feedback. Symposium participant Jeremy Howell appreciated the strong turnout and the thoughtful questions he received. “I think the energy is great,” Howell said. “I’m not sure that would be the case at every school, that undergraduate research would be taken seriously. As a student doing undergraduate research, I always felt that what I was doing was important.” History majors who chose to apply to the Honors thesis program are signing up for a serious commitment. During their final year at Carolina, students take a two-semester course to research, outline, and draft an historical essay of at least 50 pages (and sometimes close to 100 pages). Although all Carolina history majors write papers based on original research, few students have undertaken projects of this magnitude prior to embarking on their thesis project. Thus, both a faculty adviser and the instructor of the honors thesis course – this year, Kathleen DuVal – work with the students as they encounter new research and writing challenges. The process culminates when students defend their final projects in front of a committee of faculty members who grill them for an hour or more. This year’s Honors students came to their topics in a variety of ways. Jeremy Howell, who wrote his thesis on the evolution of the legend of Prester John, a mythical Christian king in Ethiopia, wanted an opportunity to learn more about African history. Michael Purello was inspired to write his thesis while studying abroad in Spain. “The available English novels were all set during the Spanish Civil War,” Purello explained. “I was reading books and also learning about it in the history classes I was taking at university there, because it’s obviously mentioned very regularly. Then I came back and continued my research.” Some students had to do original research outside of Wilson Library for the first time. Many received travel awards from the Department of History or Honors Carolina to support their work. With the funding she received, Frances Cayton did research at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University, the Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences of America in New York, and the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Columbia University. Yet for other honors thesis writers, Wilson Library offered an ideal primary source base. Emma Watts, who sees local history as an important but “overlooked” field, wanted to focus her project on UNC’s campus. Watt’s thesis, titled “‘The Wimmin Are With Us To Stay’: Women’s Social Activities at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill from 1897 to 1946,” shows how women students at Carolina used extracurricular activities to make themselves “a more integral part of the culture of UNC.” A number of the Honors thesis writers are considering graduate school in history. For them, this project provided an introduction to the sorts of questions and challenges they will encounter if they continue to pursue advanced historical research. For example, despite having access to all of the collections in Wilson Library, Watts struggled to find primary sources that included women students’ voices. “I definitely had to work outside the box because there weren’t enough of women’s actual perspectives who lived through it to build my whole paper, so I really just had to piece through what the Dean of Women was saying, what the DTH was publishing,” Watts said. “I had to fit together what the story would be, since I couldn’t get it firsthand.” Any professional historian knows the feeling—and the satisfaction that comes with finding an imaginative way to revise the project and move forward. – Aubrey Lauersdorf Oh, the Places They’ll Go….It’s time to bid farewell to our graduating seniors, who are embarking on a fascinating range of professional, service, and academic endeavors. We spoke to just a few of them to find out what they’re doing next—and why they decided to major in History. Note from the Director of Undergraduate StudiesAs always, the academic year 2017-18 included an impressive amount of daily achievements by students and faculty in the classroom, exploring history across a vast range of topics, eras, and parts of the world. This newsletter cannot pretend to do justice to all of the creativity and hard work by undergraduates, graduate-student teaching assistants, and faculty across two semesters. One class in particular, however, taught by Professor Karen Hagemann, deserves mention: students in HIST259, “Women and Gender in Europe, 18th-20th Century, produced an innovative final group project, a website “Towards Emancipation? – Women in Modern European History: A Digital Exhibition & Encyclopedia.” Beyond the regular class offerings, a number of our undergraduates presented their original research at off-campus and on-campus venues. Sophia Rupp attended the biennial Phi Alpha Theta conference at New Orleans in January, presenting a paper “There Are Those Who Drink Our Blood”: The Beilis Case and the Power of Anti-Semitism in Late Imperial Russia.” That same month, Frances Cayton presented at the undergraduate poster session at the American Historical Association in Washington, D.C., on her project “Radio Free Europe, Poland, and 1956: Impact and Incoherencies in American Psychological Warfare Intervention Efforts.”  The department was also proud to award a number of prizes and forms of financial support related to undergraduate research. Please see the list of honors below! The History department expresses it deep gratitude to the Meador, Kusa, Ryan and Boyatt families for their support of the undergraduate program in History. We also have a new undergraduate coordinator, Jeanette Jennings, who is doing an amazing job providing administrative savvy to our undergraduate program, and helped ensure that the 2018 Commencement ceremony went off without a hitch. Lastly, thanks to our undergraduate students for their energy, enthusiasm, and historical insights that continue to enliven our intellectual community anew every year. Brett Whalen |

| Faculty Spotlight |

ViewDigital Media Offer New Outlets and Challenges for Faculty

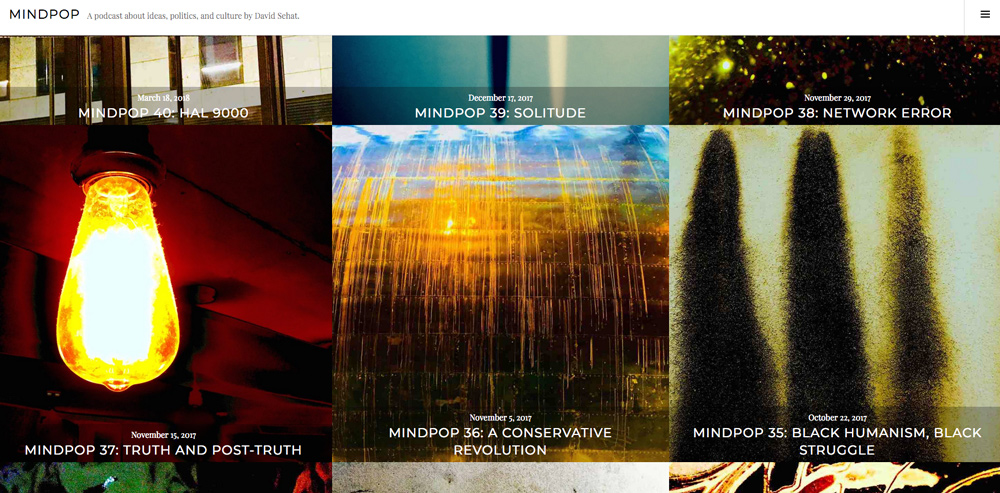

Many faculty and recent graduates are making use of these new tools. Andrews, who teaches sports and United States history, is collaborating with Jonathan Weiler, Director of Undergraduate Studies in the Global Studies Curriculum, to launch a podcast The Agony of Defeat. The podcast will discuss the intersection of sports and politics. Andrews sees it as an extension of his teaching, intended for people “who are interested in sport but don’t necessarily think about the links between sports and politics.” The University of North Carolina History alum, David Sehat (PhD, 2007) hosts a Mindpop—a podcast of sharp long-form interviews with scholars from a range of fields—now onto its fortieth episode. A major part of the appeal of podcasting and Twitter is the power of these platforms to reach new audiences. “There’s a big push here at the university to reach the public beyond the walls of the academy,” Andrews said, “That’s one of the things that I’m most proud about what this could be: educating the larger public on the types of issues we talk about at the University.” In 2015 Evan Faulkenbury helped start the Southern Oral History Program’s podcast, Press Record, while a graduate student in the history department. “Podcasts are a great way to get oral histories out of the archives and into people’s ears,” Faulkenbury said. The Southern Oral History Program designed the podcast with public accessibility in mind, sharing short clips and historical commentary. Now an Assistant Professor at SUNY-Cortland, Faulkenbury does not think podcasts or social media platforms like Twitter can replace deeper scholarship, but they can present simplified historical analysis to wider audiences. “We can reach anyone worldwide,” he said. “From students to retirees, to History Channel addicts to someone needing a good podcast to listen to on the way to work.” He said that doing history for a wider audience in a different medium “makes us think about our scholarly work in a more beneficial-to-society way, gets the word out, and keeps historians relevant in our digital media age.” There are benefits to using social media among historians as well. Faulkenbury said “Twitter is one of the best tools we can use.” The #Twitterstorian hashtag, which groups tweets by historians on Twitter, can be an excellent resource for ideas, advice, and moral support. Andrews added that Twitter has become a way for many historians to trade interesting articles. The Princeton historian Kevin Kruse (UNC History B.A., ’94) regularly tweets historical and political commentary to his eighty-nine thousand followers. Within the department, staff have used Twitter, Facebook, and the photo-sharing site Instagram to showcase undergraduate students and participate in the online culture of the University. Nevertheless, digital engagement presents some challenges. The biggest obstacle, especially for podcasting, is time commitment. Even with the help of undergraduate staff, it’s “really hard to find time to sit down and do it,” Andrews said. Faulkenbury cautioned that podcasts “have to be done right, or they can be easily ignored. There’s so much content out there already, anything we produce can easily get lost in the internet void.” Unfortunately, he added, there is often little “return on the time investment” for tenure-track professors, since most universities’ tenure guidelines do not value social media work as much as old-fashioned academic publications. The public nature of digital media also raises questions about liability for faculty. “When you’re on Twitter, are you a representative of the university or of yourself?” Andrews asked. He highlighted the case of George Ciccariello-Maher, who resigned from Drexel University in 2017 after conservative websites publicized some of his tweets. “Because I have my Twitter handle on my syllabus, I’m dedicated to only Tweeting things that have to do with sports or sports and politics.” –Joshua Tait Melissa Bullard’s Second Sailing

Originally from California, Bullard had never been to Brooklyn before seeking out the origins of a family portrait. Its subject, Luther Boynton Wyman (1804-1879), was a merchant with the famed Black Ball Line of Liverpool packets, one of the most important Atlantic shipping companies in the nineteenth century. Wyman was also a major patron of the arts in Brooklyn. Bullard spotted a wider trend. “I had a sense of Renaissance as a cultural flowering,” she said. “When I came to nineteenth-century Brooklyn history, I recognized what was happening there to be a cultural movement –a kind of Renaissance. I think other scholars may not have recognized all the connections between commerce and culture there, but rather considered the newly formed Brooklyn Philharmonic Society, Academy of Music, and Arts Association in isolation. But to observe so many cultural foundations emerging together and at the hands of people engaged in transatlantic commerce” struck her as an exciting echo of the Italian Renaissance. Brooklyn’s Renaissance offers the backstory to present-day Brooklyn’s character as an arts-friendly community. Bullard studied how nineteenth-century Brooklyn, soon to be third largest city in the U.S., was eager to bolster an image of itself as a cultural center separate from Manhattan. A group of commercial professionals, working together, established an “amazing number of cultural associations over a short period of time.” These Renaissance-style patrons “longed to have the cultural amenities a city Brooklyn’s size warranted,” Bullard said. “And they were tired of having to cross the East River to go to Manhattan for an evening performance of the philharmonic orchestra or to attend a lecture.” As she continued her research, Bullard “began to see parallels between what was happening in nineteenth-century Brooklyn and what had occurred in Italy in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries,” she said. One major parallel concerned how a mercantile elite purposefully promoted the cultural affairs of their city and used culture to create community bonds. This model resembled the merchant patronage the Medici had fostered in Italy. The Brooklyn patrons of the arts Bullard studied were emulating the parallel she explored. These Brooklynites drew upon their transatlantic networks, especially in Liverpool. That city had experienced its own cultural flowering a generation earlier, and key figures there “had fallen in love with the Italian Renaissance” and even styled themselves and their city after the Florence of Lorenzo de’ Medici. Her focus on the nineteenth century brought some added benefits. Compared to the challenge of deciphering five-hundred-year-old Latin and Italian manuscripts, research in a relatively recent century—in a primarily English-speaking community—presented far fewer paleographic obstacles. This project also allowed Bullard to work extensively with newspapers, a source-base unavailable in the Italian Renaissance. She is currently developing a website with historic maps that track the dynamics of Brooklyn’s Renaissance during this crucial time. Bullard urges other scholars to venture beyond the boundaries of their formal academic training. “Go for it!” she said, “It’s exciting, it’s invigorating, and it will make you a better historian because you will gain a much broader comparative perspective.” At the same time, she recognized that this flexibility may not be available to junior scholars. One must develop a “solid base” and “thorough engagement” in a particular field before expanding outward. Bringing her skills and perspective to a new field was “a plus,” Bullard said, “but it was also a luxury that as a senior scholar I could indulge.” –Joshua Tait Prizes, Honors, Accolades—Part IIThis spring, Kathleen DuVal received a fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, which will allow her to spend next year working on her next book, a history of American Indian dominance prior to 1850. DuVal was also elected a member of the Society of American Historians this year. UNC honored William Sturkey with one of this year’s Diversity Awards, which recognize “work advancing an inclusive climate for excellence in teaching, research, public service and academic endeavor.” The UNC General Alumni Association recognized Lloyd Kramer with the Faculty Service Award, which honors faculty members who have “performed outstanding service for the University or the alumni association.” |

| Alumni Spotlight |

ViewAlum John Hall Writes Official History of Counter-Terrorism for the Joint Chiefs Professor of U.S. Military History (photo courtesy UW Madison) The History Office of the Joint Staff asked Hall to write the official history of the Pentagon’s war against violent extremism. He will trace the development of counter-terrorism policy from the 1990s to the present. Hall is writing a history that is still unfolding, so he gathers evidence by not only researching at the Library of Congress and the National Archives, but also by observing meetings among senior Pentagon officials. Because Hall’s official history will consult documents considered “top secret,” it won’t be publicly available in its entirety. Although Hall has only worked in the History Office for a short time, he already recognizes that his colleagues are committed to producing serious official histories. “Official history can have some negative connotations that go along with it, and in some instances, that’s certainly warranted,” Hall explained. “None of the work that we do is designed to tell a flattering story, necessarily, of what the U.S. military has done in the past, or what the Joint Chiefs of Staff in particular has done. The principal function of the History Office is to provide critical, incisive historical perspectives to inform contemporary decision-making and to shed historical light on challenges that the Joint Staff and its leaders are confronting on a regular basis.” Sometimes, urgent requests from the Joint Staff interrupt Hall’s research for his official history. “If there’s something that you might read about in the news, be it a contemporary security challenge or issue, typically a senior leader within the Joint Staff wants to know the historical backstory to that issue and wants to know if there are potentially historical episodes that may have any relevance to goings-on at present.” Hall said. “We’ll write, then, point papers and special studies that are designed to provide that historical perspective.” Hall’s research on the origins of contemporary policy takes him beyond his formal academic training. At UNC-Chapel Hill, he worked with specialists in American Indian history, including Theda Perdue and Michael D. Green, and with historians of the early American Republic, including Don Higginbotham, Richard Kohn, William Barney, and Joseph Glatthaar. Hall’s dissertation, which became his book Uncommon Defense: Indian Allies in the Black Hawk War (Harvard University Press, 2009), was an American Indian military history focused on the territory that would become his home state of Wisconsin. The position with the Joint Chiefs is not the first time that Hall’s military and academic careers have intersected. He came to UNC for graduate school after the Army selected him for Advanced Civil Schooling. After completing his M.A., he taught at West Point for three years while writing his dissertation. Recently, he worked remotely as a historian for the U.S. European Command. Hall’s position in the History Office of the Joint Staff will last only a few years. After that, he will return to teaching fulltime at UW-Madison. Yet even from the Pentagon, Hall continues to fulfill obligations to his home institution and the historical profession. He is currently teaching a graduate seminar over Skype, and he was elected Vice President of the Society for Military History for two years. From afar, he is also working with colleagues at UW-Madison to create a War in Society and Culture program, which is modeled after UNC’s Peace, War, and Defense program, among others. Hall sees his time on active duty as contributing to, rather than detracting from, his career as a historian. “My expertise is going to remain in the borderlands of American Indian and U.S. history in the era of the early Republic, so I’m interested in the opportunity to perhaps broaden the topics on which I might write, but I think the real dividends, for the War in Society and Culture program and the students who are in it, will be my breadth of experience in more contemporary affairs.” –Aubrey Lauersdorf |

| History in Our World |

|

View

No items found

|

| Out of the Archives |

ViewDepartment by the Decade: The 1940sWorld War II had profound effects on the American home front—including UNC’s Department of History. When the war came to Carolina, our faculty, staff, and students quickly responded to the nation’s changing needs. After the United States declared war in late 1941, UNC faced a reduction in enrollment as young men and women joined the armed forces. (The University opened its doors to women in the late nineteenth century, but it would continue to exclude African Americans until the 1950s.) History courses were not immune to declining enrollment. Southern historian Albert Ray Newsome, who served as Department Head during the war, counted 333 undergraduate students in history courses in the first months of 1943 and only 233 the following fall.  To withstand this financial shock, UNC’s administration sought opportunities to provide military training using campus facilities and instructors. In September 1943, University President Frank Porter Graham announced that UNC would enroll approximately 1,300 V-12 Navy College Training Program students and 250 Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP) language trainees, among other programs. Although not as well-known as UNC’s Navy Pre-Flight Training School, the V-12 and ASTP programs trained officers and specialists to help meet increased personnel needs in those branches of the armed forces. By the war’s end, neither students nor faculty would ever be the same. The military training programs kept UNC and the Department of History afloat during the war. In 1943, President Graham reminded faculty members that “the University is one of the fortunate institutions of this country in that it is able to operate and maintain the salaries of its staff, while many other institutions are closing up or reducing staff.” Enrollment in history courses skyrocketed as a result of the Navy and Army programs. In the summer of 1943 alone, 788 Navy students took history classes. Because the Navy wanted its officers to have training in history, the Department suddenly struggled to find instructors for all of its courses. The men who made up the tenured faculty increased their teaching loads by 25%, and many deprioritized their research during the war. The Department also hired temporary instructors to teach introductory history classes for the Navy V-12 program, including two local women who were trained historians. As in other industries, the unavailability of men to teach history on the home front gave women new employment opportunities. Indeed, only a few years earlier, the Department had denied a graduate fellowship to a woman even though she had “the strongest application” of all 69 candidates. The professors who reviewed her application admitted that “she undoubtedly has everything—personality, intellectual ability, scholarship and teaching ability and experience,” but they also believed “that men were more suitable for the relationships which the work of the fellowship necessitates.” As the Department adjusted to increased personnel demands, individual instructors adjusted to teaching in a strict military setting. The Navy and Army standardized the historical narratives that they wanted their students to learn, and they provided V-12 and ASTP instructors with content guides and course materials. Sometimes, professors were surprised by Army and Navy expectations. Understandably, Newsome initially arranged for Europeanists to teach the Navy’s required “Historical Background of World War II” course. However, he later learned that the Navy expected the course to be an introduction to United States history that also emphasized current affairs, and he had to reassign instructors accordingly. Although most faculty members supported the war effort as Army or Navy instructors, some played more active roles in World War II. Professor J. Caryle Sitterson was drafted in the spring of 1942, but he was soon discharged for medical reasons and resumed teaching at UNC. Professor George E. Mowry, a specialist in the American Progressive era, left UNC to write manuals and textbooks for the U.S. Army Quartermaster, the officer who oversees the distribution of supplies within the Army. He did not return to UNC after the war. Professor Howard K. Beale served as Director of the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council. This council relocated Nisei college students from internment camps to colleges throughout the country. (Nisei were people born in the United States whose parents were born in Japan.) When the war ended in 1945, the department returned to a state of relative normalcy. Without V-12 and ASTP obligations, faculty resumed teaching their usual courses. As soldiers came home, civilian enrollment at UNC increased, and the Department happily reported an uptick “in course enrollment, history majors, and graduate students.” In the aftermath of a global war, however, faculty members increasingly recognized the importance of teaching histories beyond the United States and Western Europe. In the final years of the 1940s, the Department worked to expand the breadth of its course offerings to include the histories of Latin America, China, Japan, and Russia.  –Aubrey Lauersdorf |

| Graduate Student News |

ViewSoldier-Scholars Bridge the Classroom and BattlefieldIn 2008, Captain Lauren Merkel graduated from the University of North Carolina with a degree in Political Science. A cadet in the Reserve Officer Training Corps, she was commissioned as a junior officer in the United States Army. Merkel served in Afghanistan, Jordan, Kosovo, and in the United States. In 2016, she entered graduate school at her alma mater, this time in History. She won’t be here long: next fall, she will leave Chapel Hill for the United States Military Academy at West Point, where she will teach cadets in a required course on the history of twentieth-century warfare.  This demanding career trajectory has become surprisingly common at UNC. The History graduate program has a strong reputation and long-standing relationship with the Armed Services. The Department has helped to educate a new generation of officers and bring academic methods and thinking into the military. Graduates of the program include Lt. General H. R. McMaster (PhD, 1996), a former National Security Adviser under President Trump, and retired Colonel Gregory Daddis (PhD, 2009), a highly regarded historian of the Vietnam War. Typically, the department accepts two mid-career Army officers to the graduate program every three years. For these officers, the academic training they receive at the university is both an important step for their military career and an opportunity for intellectual growth. Recently, the department has graduated John Roche (PhD, 2015), Brian Drohan (PhD, 2016), and Rory McGovern (PhD, 2017). The Army provides funds for officers to pursue graduate education at a civilian university like Carolina. Officers are responsible for choosing a research topic and getting accepted into a program, although the Army’s relationships with some universities inform the officer’s final choice between programs. For most, the immediate purpose of graduate training is to become instructors at West Point, where they teach for two to three years. More than half of West Point’s teaching staff is composed of Army officers trained at civilian PhD programs. “Using military officers not only keeps West Point focused on its fundamental mission as a professional military academy, but it also helps to create a broadly educated Officer Corps in the army,” said Drohan. The Army requires a Master’s Degree to teach. So Army Officers studying at Carolina follow an accelerated path to earn their Masters and reach “All But Dissertation” status within two years. Then they are transferred to West Point, at which point, Merkel said, “it is all on” her to write her dissertation in her spare time while teaching. This is a challenging pace for any graduate student. “I definitely came in feeling lost; I’d never even heard of Foucault before,” Merkel said. “I felt very overwhelmed my first year but I think most people do.” Officers at UNC study a wide variety of subjects in preparation for their teaching assignments. The History Department’s strength in a variety of fields and time periods—as well as its specific depth in military history—make it attractive to Army officers. Merkel highlighted Carolina’s strength in both Middle Eastern and military history as factors that drew her to the department. She has been well supported by the department. In particular, Cemil Aydin, professor of Modern Middle Eastern history, and Wayne Lee, the Dowd Distinguished Professor and a retired Army combat engineer, have been important resources. Lee especially “understands both sides of the system and is able to provide very specific, tangible advice,” she said. Merkel also highlighted her “supportive cohort,” saying that graduate school had “a very different sort of intensity from what I’ve been used to and a really nice change of pace.” Within the Army, there is an increasing emphasis on continuing education throughout officers’ careers. Merkel said that mid-career officers feel some pressure to earn a Master’s degree; a variety of Army programs facilitate this. “I think that a cultural shift is in progress,” Merkel said. “There is a real recognition that war is really complicated” and “the Army is beginning to realize that the critical thinking skills that come from a higher level of education are critical for the Officer Corps.” In part, appreciation for higher learning at the highest levels of the Army’s command structure has driven this transformation. A number of officers in key positions, including David Petraeus and H. R. McMaster, “found value in their own education” and have shaped the organization from top down, Merkel said. We “cannot draw specific tangible lessons from history,” she said. But “history can direct the right questions, even if it doesn’t provide answers.” History “provides a framework for understanding social factors in a very broad sense and [equips officers with] a better ability to evaluate them.” Drohan added that the skills he developed in the graduate program have been “vital” in his work as a strategic planner. “I’ve also found that I’m better at identifying biases, logical fallacies, and weak points in an argument,” he said. Other graduate students also learn a great deal from the Army officers or veterans who bring a range of combat experience to the classroom. In his first seven years in the Army, Drohan spent time in Iraq, Kuwait, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh–all former British colonies or protectorates. Those experiences sparked his interest in the history of colonialism and the British Empire. His experiences in Iraq and Sri Lanka in particular informed his dissertation research on human rights activism in counterinsurgencies in the British Empire. Eric Burke, an Army veteran and PhD candidate, said his “experience as an infantryman provided me with key insights into the kinds of problems soldiers care most about, and the kinds of issues they find most compelling.” Academia and the United States Army are, obviously, very different organizations, but Burke believes engagement between the institutions can be fruitful. “The Army has a tremendous amount to learn from the academy,” he said, “most especially that war will always involve people and people are dizzyingly complex.” Teachers and students in the humanities know “this better than probably anyone alive.” Yet his military service helped him see the essential human sameness that cuts through that complexity. As a soldier, Burke said he had “the great good fortune” “of risking my life alongside men whose social, cultural, political, and religious views could not have possibly contrasted more with my own. I would have given my life without a second thought for any one of them. Many of them did so for me.” Those were exceptional circumstances, he admitted, but now as a historian, Burke thinks “a little more of that kind of mutual respect and caring that transcends all the divisions in our society could certainly benefit any and all institutions, the academy very much included.” For Merkel, working within both institutions and cultures requires shifting her mindset. “When I am here I am a historian; I try and differentiate between historian mode and soldier mode.” She said she does not approach her project from the perspective of a “we” or and “us” “as in the United States,” but rather as a historian. In terms of her professional identity, however, there is no question: “I’m definitely a soldier first.” –Joshua Tait Instructors Bring Public History into the ClassroomUNC students often expect to write academic papers that no one but a professor or teaching assistant will read. Yet increasingly, instructors in the History department are designing assignments that ask undergraduates to use the skills they learned in class to reach a much broader audience beyond the walls of the university. Mary Elizabeth Walters, a Ph.D. candidate and teaching assistant for Professor Joe Glatthaar’s course “War and American Society, 1903 to Present” this semester, helped each student create an oral history of a veteran and write a feature article based on their interview. Because soldier experience in war is a central theme of the course, the oral histories fit naturally into the curriculum and allow students to hear a broader range of perspectives. Many students in the class do not have family members in the military, so the instructors directed them to local veterans’ organizations. “I had a slight ulterior motive [in sending the students] to the various veterans’ organizations,” Walters admitted. “A lot of them have older vets who have very large mobility issues, and they don’t get out much, and they don’t get to tell their story much, and it means the world to them when they get a young person who is genuinely interested.”

Ph.D. candidate Robert Colby, who trained in digital history methods at UNC, took a similar approach in a class he recently taught as a visiting instructor at Elon. To help his students understand how the policies of Reconstruction played out on the ground in the South, Colby asked students to transcribe documents from the National Museum of African American History and Culture that had been scanned for the online Freedmen’s Bureau Records Transcription Project. “I think they really benefited from the sense that someone was actually going to use [the transcription], that it’s not some sort of busywork. I really emphasized heavily that, for genealogists, [the Freedmen’s Bureau Records are] a rich and untapped tool,” Colby said. UNC instructors also ask undergraduate students to research and write histories intended for the campus public. In fall 2017, students in Professor James Leloudis’ undergraduate seminar “Slavery and the University” studied records in the University Archives to help the Chancellor’s Task Force on UNC-Chapel Hill History. To complete their final project, the students worked in groups to write papers on three important themes that they identified in their research: slavery and UNC’s finances; the daily lives of enslaved people at UNC; and enslaved people’s work to build UNC’s campus. “We tried to emphasize writing this paper in a way that isn’t like your typical course paper. We tried to emphasize being concise, saying what you want to convey in as few words as possible, and using simple, non-academic language while still carrying the full complexity of the subject matter,” explained Brian Fennessey, a Ph.D. candidate who was the research assistant for the course. Asking students to explain complex ideas to a general audience reinforced the goal of the papers—to serve as a starting point for the Chancellor’s Task Force as it develops a comprehensive approach to teaching campus history. In fact, Caroline Newhall, a Ph.D. candidate who works as a research assistant for the Task Force, drew on the students’ work in her recent article about enslaved people’s roles in the construction of Old East. Like Colby, Fennessey found that students were motivated by the fact that their work would make a public contribution. “I was very pleasantly surprised by how quickly the students became interested and really invested in what we were doing. They really made the projects their own and took clear joy in presenting the information to Chancellor Folt,” Fennessey said. When Chancellor Folt visited the class, Leloudis and Fennessey encouraged the students to share with her the documents that they found most significant. They chose a document that revealed that the University dedicated two dollars of students’ nineteen-dollar tuition to pay professors to use their slaves for tasks like building fires or carrying messages between buildings. “Seeing that every student contributed to slavery through their student fees, I think, was something powerful that the students connected with, and they were clearly invested in showing that to Chancellor Folt,” Fennessey explained. –Aubrey Lauersdorf Prizes, Honors, and Accolades—Part III

The prize committee praised Snyder’s book, Great Crossings: Indians, Settlers, and Slaves in the Age of Jackson (Oxford, 2017), as a beautifully written narrative of the complex encounters between Native Americans, African-Americans, and Anglo-Americans, particularly through the Choctaw Academy in the Kentucky borderlands. The book brings “an intriguing cast of characters to life: the Indian-killer turned educator and politician Richard Mentor Johnson, founder of the school; Johnson’s enslaved wife and daughters, Julia, Imogene, and Adaline Chinn; dozens of brilliant and sometimes resistant Native students—Peter Pitchlynn, Joel Barrow, and Wash Trahern among them—whose lives were irrevocably changed by their years at the academy.” Great Crossings “makes new and important arguments through a gripping story, brilliantly told.” Snyder is the McCabe Greer Professor of History at Pennsylvania State University. Our current graduate students are already well on their way to such accomplishments. If you thought that the list of undergraduate awards was lengthy, then settle in and grab a cuppa before you click on this link to all the fellowships and prizes won by our graduate students this year. Graduate School Summer Research Fellowship Royster Dissertation Completion Fellowship Graduate School Dissertation Completion Fellowship Druscilla French Graduate Fellowship Thomas S. Kenan II Graduate Fellowship Graduate School Off-Campus Dissertation Research Fellowship Quinn Dissertation Completion Fellowship Association for Jewish studies Dissertation Completion Fellowship National Humanities Center Triangle University Internship Program Clein Internship Awards Fulbright-Hays Fellowship Maynard Adams Fellowship for the Public Humanities Archie K. Davis Summer Research Fellowship 2017 Association for Slavic, East European, and Eurasian Studies (ASEEES) Kathryn Davis Fellowship for Peace Dean’s Graduate Fellowship Peter Filene Teaching Award TA Teaching Award Archie Davis Fellowship SOHP Jacquelyn Dowd Hall Summer Graduate Research Fellowship SOHP Field Scholars CSAS Summer Research Grant Mellon-CES Dissertation Completion Fellowship CSAS Summer Research Grant Americas Research Network Research Fellowship Federal Foreign Language and Area Studies Fellowship |

| Undergrad News |

|

View

No items found

|

Gifts to the History Department

The History Department is a lively center for historical education and research. Although we are deeply committed to our mission as a public institution, our “margin of excellence” depends on generous private donations. At the present time, the department is particularly eager to improve the funding and fellowships for graduate students.

Your donations are used to send graduate students to professional conferences, support innovative student research, bring visiting speakers to campus, and expand other activities that enhance the department’s intellectual community.

|

To make a secure gift online, please click “Give Now” above.

The Department also receives tax-deductible donations through the Arts and Sciences Foundation at UNC-Chapel Hill. Please note in the “memo” section of your check that your gift is intended for the History Department. Donations should be sent to the following address:

UNC-Arts & Sciences Foundation

Buchan House

523 E. Franklin Street

Chapel Hill, NC 27514

Attention: Ronda Manuel

For more information about creating scholarships, fellowships, and professorships in the Department through a gift, pledge, or planned gift please contact Ronda Manuel, Associate Director of Development at the Arts and Sciences Foundation: ronda.manuel@unc.edu or (919) 962-7266.