Fall 2017 – Archives

| Expand All | Collapse All |

| Department News |

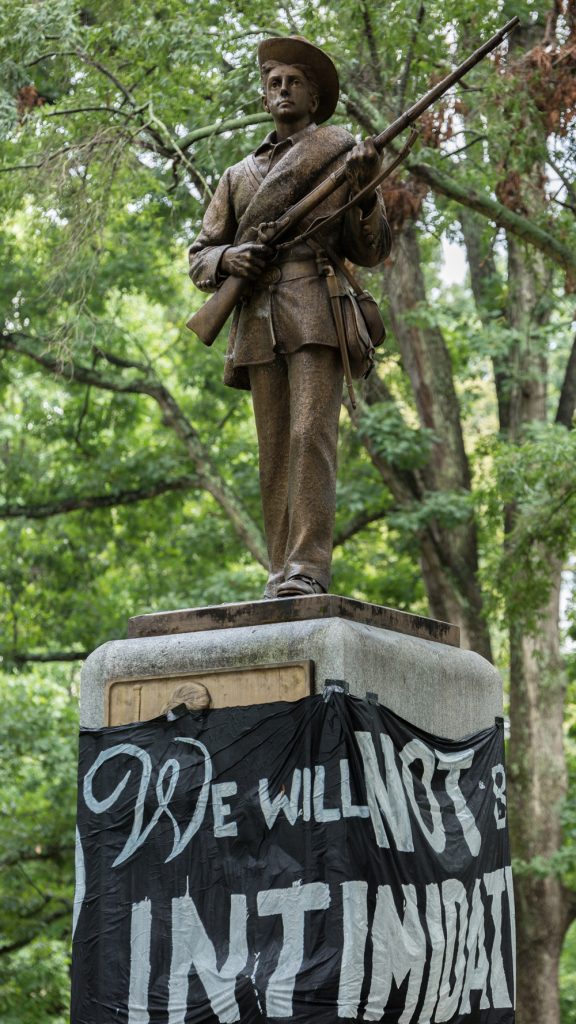

ViewHistory Majors Undertake Summer Research Near and Far While many undergraduate History majors have the opportunity to mine archival collections in Wilson Library, a few lucky students are able to travel the world for research during their time at UNC. Thanks to the Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) offered by the Office for Undergraduate Research in the College of Arts and Sciences, students like Lacey Hunter can pursue projects that take them beyond the collections available on campus. Hunter, a senior double majoring in History and Archaeology, applied for SURF funding during her junior year after deciding that she wanted to write an honors thesis. Hunter was one of only 60 undergraduate students in the College of Arts and Sciences awarded a SURF. History majors Henry Hannapel, Christopher LaMack, Alexander Peeples, and Jack Walsh also received SURF grants in 2017. Hunter used her SURF funding to visit archives in Washington, DC and London, where she examined primary sources for her thesis, tentatively titled “Where to Draw the Line for Liberty: Perspectives on African-American Freedom Following the American Revolution.” “I look at this individual, [British Major-General] Sir Guy Carleton, and I look at his life and how his life reflected or did not reflect greater trends in the British administration and British military,” Hunter explained. “As the empire is expanding, they’re controlling more foreign peoples, and [I ask] how they dealt with that and how they viewed people who were very different from them, in their minds.” Hunter was inspired to pursue this intellectual history in Kathleen DuVal’s class, “Revolution and Nation-Making in America, 1763-1815.” DuVal asked students to read historian Cassandra Pybus’ Epic Journeys of Freedom, which discusses Guy Carleton and George Washington’s negotiations over the futures of African-Americans who had fought for the British, who had promised them freedom in exchange for joining the Loyalist cause. “I thought that was so interesting, and it was very new to me, and that basically is what inspired my idea. I have obviously taken a different approach than [the author] did, because she follows the individuals that were affected by these higher-up decisions, and I’m looking at those higher-up decisions and where those decisions and ideas came from,” Hunter said. Her thesis adviser is Wayne Lee, who has helped her understand “military details and how the eighteenth-century British military functioned,” she said. While Hunter’s SURF took her across the Atlantic Ocean, other History majors used their funding to perform research here on campus. Henry Hannapel, a junior majoring in History and Economics, wanted to understand how student veterans transition to civilian life at UNC. “I look into how student veterans at UNC are transitioning, what their experiences are like, and learn from them so we can better tailor our university to meet what they need,” Hannapel explained. While he initially considered using existing oral histories for his project, Hannapel ultimately decided to do his own interviews with veterans currently enrolled at UNC. Eventually Hannapel, who is working closely with the Carolina Veterans Association, wants to create an online resource for veteran and non-veteran students at UNC. He envisions this website as “an informative place where people can go to learn about student veterans, the military, and military culture.” Hannapel is working under the direction of a faculty adviser in the Department of English, but he still sees his training in History as essential to his project. “Something I’ve gained from my pursuit of a History degree is learning how to approach problems in a different way than maybe someone with a Biology degree or a Mathematics degree,” Hannapel said. His History courses helped him understand the complex contexts that shape an individual’s worldview. “I really wanted to get to know the student veterans that I was interviewing, but also I wanted to try to understand how they saw civilian students and how civilian students saw them, how that’s different, and how we can work together to attack that issue and try to solve it.” Aubrey Lauersdorf History Department Calls for the Removal of Silent Sam The Department of History has added its voice to growing calls to remove the Confederate Memorial from campus. In the October 4 statement, the Department urged UNC and state officials to “pursue every avenue to remove the ‘Silent Sam’ monument” from its “prominent place” on campus. The History Department joins several other departments and schools in this call for action, including Anthropology, Religious Studies, and the School of Law, as well as the Chapel Hill Chamber of Commerce. According to William Sturkey, an assistant professor who specializes in 20th-century African American history, monuments like Silent Sam were built by “white supremacists to, in part, promote or justify the morality and political mission of white supremacy.” Such “relics” of Jim Crow “don’t work outside a Jim Crow system, where people of color are allowed to attend and work at the University of North Carolina,” he said. Silent Sam has been controversial since the end of Jim Crow in Chapel Hill, but the most recent round of student-led protests began after the August “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, where white nationalists protested the removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee from the University of Virginia campus and one counter-protester was killed. “For me, the biggest issue with Silent Sam is that it sends a message to non-white students and campus members that they and their concerns are not fully welcome here on campus,” said Jennifer Standish, a History graduate student involved in an ongoing student protest of Silent Sam. The public response to student protests has been mixed. “There have been some really productive conversations,” she said, “but also some very hostile and violent ones as well.” History faculty have worked hard to engage the wider community in a dialogue about the meaning of Silent Sam. In late August, William Sturkey and Harry Watson, the Atlanta Alumni Distinguished Professor of Southern Culture, participated in a Carolina Public Humanities panel moderated by Lloyd Kramer, history professor and director of Carolina Public Humanities. Watson told the audience that while the meaning of symbols shifts over time, Silent Sam still has an explicit pro-slavery meaning and “is a rallying point for those who celebrate white supremacy today.” As a community, he added, we must show our common commitment to a non-racist society. William Sturkey and Fitz Brundage, department chair and the William B. Umstead Distinguished Professor, also discussed Silent Sam in a Community Forum on the television station WCHL and Brundage also appeared on PBS Newshour to speak about Confederate memorials. In the Raleigh News & Observer, James Leloudis, a history professor who specializes in the modern South, outlined the origins of the memorial. UNC trustees and the United Daughters of the Confederacy began planning the statue in 1908 and dedicated it during spring commencement in 1913. Those dates are important: Silent Sam was built during a politically charged period of Confederate memorialization. Before 1902, North Carolina had only six Confederate memorials; between 1902 and 1926, white North Carolinians built fifty-three. In a widely shared article in the online magazine Vox, Brundage noted that “the installation of the 1,000-plus memorials across the US” – including Silent Sam – happened while “the South was fighting to resist political rights for black citizens.” With no public consultation, organizations like the United Daughters of the Confederacy sponsored the installation of pro-Confederate statues in prominent places. The process, Brundage argued, was one of “private groups colonizing public space” for a white supremacist agenda. Much of their racist propaganda “was academic,” Sturkey said. “It was teaching, going into schools, going into colleges, producing scholarship, having essay writing contests” with a pro-Confederate slant. Since the 1960s, historians have corrected the historical record but the statues remain on the grounds of many civic institutions. Part of the struggle is that “we can’t even get people to admit that that Jim Crow was even that bad because that would acknowledge that there might be some sort of historic effect that has resulted in contemporary inequalities and disadvantages for certain people,” Sturkey added. He also noted that the deadly violence of the Charlottesville rally, as well as Dylann Roof’s murder of nine African-Americans at a church in Charleston in 2015, show how these monuments are viewed by the “worst elements in our society.” “Dylann Roof celebrated the Confederacy,” Sturkey said, “and celebrated those Confederate monuments and used that to bolster his racial superiority in a way that allowed him to sit in a church and kill nine people…these things are very meaningful to a lot of people and can in fact be dangerous when interpreted the wrong way.” Speaking and writing about the historical context of Silent Sam is, to these professors and students, consistent with the mission of UNC’s History Department. “If you work at a history department at a public university then you are a public historian,” Sturkey said. “When these issues come along I have an opportunity and a duty even to help contextualize these things for the public so that they can be better informed about what might happen with these statues or what they might actually represent.” The Department’s statement on Silent Sam suggests that if moved “to an appropriate place,” the monument might “become a useful historical artifact with which to teach the history of the university and its still incomplete mission to be ‘the People’s University.’” At present, however, the statue continues “to promote malicious values that have persisted too long on this campus, in this state, and in this nation.” The Department website lists further resources on this subject. Joshua Tait Note from the Director of Undergraduate Studies The Fall 2017 marked a number of firsts for undergraduate studies in History, starting with the creation of a new Undergraduate Lounge in Hamilton 551, a community space for majors, minors, and other history students along with activities relating to Phi Alpha Theta and the History Club. Many thanks to the History office assistant Sharon Anderson for helping to plan and install the new lounge.  The History Department also staged its first “Pit Sit” during University Research Week (October 9-13), hosting a table where students could discuss the dynamic opportunities for undergraduate historical research in the discipline of History. In particular, as part of research week, the department was proud to feature Traces, our award-winning departmental journal that features publications by undergraduate and graduate students. Last but not least, History has a new undergraduate coordinator, Natalie Albertson, who is already doing an amazing job providing administrative savvy to our undergraduate program. Brett Whalen |

| Faculty Spotlight | ||

ViewCo-Teaching Brings Benefits and Challenges to the Classroom

Last fall, professors Katherine Turk and Benjamin Waterhouse combined forces to teach a sixty-person undergraduate course on “America in the 1970s.” They alternated lectures and took turns leading weekly recitation sections. Despite some challenges, both saw great benefits for both students and faculty. The experience was “very much worth it and I think the students got that as well,” Waterhouse said. So why don’t we do it more often? The Center for Faculty Excellence advises faculty that “your peers are your best teachers,” and “America in the 1970s” bore this out. “We have a very constructive and very collegial department yet our teaching is often done in isolation,” Waterhouse said. Simply sitting in on another faculty members’ lectures can be “incredibly interesting and educational – both in terms of the subject matter and in seeing the way someone else teaches.” So the chance to teach together was an even greater—and more demanding—“opportunity to learn from each other.” Turk said that she “gained new insights about myself as a teacher.” “Co-creating a course from scratch led me to reevaluate my own habits in syllabus design, assignments, and course structure.” Co-teaching prevents the isolation that faculty sometimes feel in teaching, the burden of “making all these make-or-break decisions on your own,” said Waterhouse. Since both professors lectured and ran recitations, the students got to know two faculty for the price of one. If “I just taught a sixty person class with a TA I wouldn’t get to know them nearly as well,” Waterhouse said. “Content aside, that exposure was something the students liked.” The biggest challenge the professors faced was ensuring the class’s thematic unity, balancing one set of research interests and expertise with the other (Waterhouse is primarily a historian of American business, while Turk focuses on American women’s history). But the presence of two experts gave students a more holistic understanding of the 1970s. Students said that the course was “greater than the sum of its parts,” said Waterhouse. Turk emphasized that they “were able to demonstrate, in our divergent emphases and answers to historical questions, that history is a dynamic discipline of debate and interpretation.” Other History professors have collaborated to help students compare cultural phenomena in different societies: in 2015, Sarah Shields and Flora Cassen co-taught a course on “Antisemitism and Islamophobia.” Co-teaching also offers the possibility of exposing students to alternative ideological viewpoints. At Princeton, the leftwing scholar Cornel West and the conservative legal theorist Robert George have taught together, capitalizing on their intellectual differences. George told the Princeton Alumni Weekly that this fruitful disagreement is part of “the possibility of leading a truly examined life.” Waterhouse was wary of too much disagreement in co-taught class. There is a place for historiographical or political disagreement in co-taught classes, he allowed. But “if you go in and do some sort of CNN Crossfire style thing with two diametrically opposed positions – students hear that all the time.” He stressed that the differences between his and Turk’s approaches were “more refined and higher-order.” “We’re not arguing with each other. If anything, we’re arguing the same point from different directions,” he said. The students could see each historian approach the subject with different methodologies, focused on different kinds of evidence, which is a much “higher level way of thinking” than “‘well, this is the Waterhouse view and this is the Turk view.’” The College of Arts and Sciences has stressed the possibilities of co-teaching. Dean Kevin Guskiewicz called for interdisciplinary proposals last fall and the College announced six new team-taught interdisciplinary courses in 2017. However, Waterhouse suggested that team-teaching is “even more complex” across disciplinary lines. Determining learning outcomes and assessments may be a challenge for faculty with very different training. Interdisciplinary teaching is not an impossible challenge, Waterhouse said, “but one that runs the risk of creating two alternative interpretations that do not synthesize.” Some critics suggest co-teaching allows faculty to earn equal credit for less work. Waterhouse noted, however, that because he ran half the recitations, the course required more face-time than a sixty-person class with one teaching assistant. The University of Pennsylvania anthropologist John L. Jackson wrote in The Chronicle of Higher Education that developing co-taught classes that are “more than two distinct pedagogical ships passing one another in the dark curricular night” is in fact more work than teaching a regular class, not less. The greater obstacle to co-teaching may lie in the university’s concern that every department maximize student enrollment. “Professor Turk and I would have brought more students into the department if we had each taught a 120 student class with two TAs instead of sharing sixty students,” said Waterhouse. “That’s the tradeoff.” Nevertheless, Waterhouse recommends co-teaching wholeheartedly. “We have a lot of faculty members who have thematically overlapping expertise but in different parts of the world, different fields, and different time periods.” As a world-class research university, UNC offers students the chance to work with experts across a wide range of fields. “The more they can make use of that expertise, the more they can see us as practicing historians—not just the person who’s lecturing at them—the better.” Joshua Tait |

| Alumni Spotlight |

ViewNovelist Katy Simpson Smith Says Her History PhD Informs Her Fiction Who says a historian has to stick to the facts? When Katy Simpson Smith, PhD ‘11, got a major book advance from HarperCollins, she left her adjunct teaching position at Tulane University to write fulltime—and now she’s the author of two acclaimed historical novels. Her historical training continues to inform her work, and historians and novelists might learn from one another’s approaches, she said. “I’ve always loved telling stories,” Smith said, “and I’ve always loved the past which is just a landscape of stories waiting to be told, or retold.” History has become fertile ground for Smith’s fiction. The Story of Land and Sea (2014) traces a family in coastal North Carolina in the aftermath of the Revolutionary War. Smith’s second novel, Free Men (2016), imaginatively recounts a murder committed by a Creek Indian, a white man, and an escaped slave and the circumstances that drew them together. Smith blends a deep understanding of the American past with an empathetic sense of shared human experience. The New York Times praised her “spare, rhythmic prose” and “refusal to serve up false redemption.” These novels grew from the research that Smith did for her dissertation on colonial and early republican womanhood in the American South, directed by Kathleen DuVal and Jacquelyn Hall. “Having that familiarity with late 18th-century thought and behavior was invaluable in creating a sturdy foundation for my fictional fancies,” she said. In her dissertation, a cross-cultural study of black, white, and native mothers in the American South, Smith argued that motherhood was the defining experience in early American women’s lives. Women embraced motherhood because it provided purpose and power within their communities. However, despite the universal role of the mother across cultures, Smith concluded that little sense of female solidarity extended across racial lines. In 2013 Louisiana State Press published the book based on her dissertation, We Have Raised All of You: Motherhood in the South, 1750–1835. While in graduate school, Smith balanced research demands with fiction writing. “I can’t say when I found the time to work on short stories,” she said, but she and several graduate students formed an “informal fiction writing club.” She also took advantage of the University’s resources. She shared her work with Dave Shaw, a local writer who works for the Center for the Study of the American South. In 2009 she took an online fiction class at the Friday Center before applying to an MFA program at the Bennington Writing Seminars in Vermont.

After graduation, Smith felt she must either “land a tenure-track teaching position, or throw history to the wind.” This dichotomy “can partly be blamed on youth,” but she also noted that the “pipeline mentality” of graduate programs—the sense that a PhD is a rigid process leading to one fixed end—“can contribute to students feeling a bit desperate.” Embracing fiction as a career has brought challenges. Smith had to “unlearn the rules about evidence and allow myself to invent.” She could “step out of the academy’s confining linguistic suit and shake things loose a bit…Though it felt liberating, I also know that the discipline I learned at UNC still informs how I write.” Good historical writing is a powerful model, Smith said, and “the history faculty at UNC” are “some of the most inventive and most humane writers I know.” Ultimately, Smith realized that the stories she wanted to write were compatible with—and even demanded—an appreciation for historical thinking. “My fiction is heavily research-based, no matter what era I’m writing about, and I wouldn’t have the skills or stamina to do this without my UNC training.” “History is such a looping, circular thing,” she explained, “I’ll never get tired of digging in that soil for explanations and for glimmers of a different way forward.” Smith believes fiction and academic history can enrich one another. “Historians can learn from novelists not to be wary of empathy.” And “novelists can learn from historians that human action never occurs in a vacuum.” She tries to “balance historical specificity” with “a kind of universal human spark.” Of course, “‘universal’ is a dirty word for historians, and so it should be,” but “in writing fiction part of our job is to knit together the reader and the character with a common, recognizable thread.” For historians, too, this connection is “vital in awakening in the modern reader a necessary empathy.” Joshua Tait |

| History in Our World |

|

View

No items found

|

| Out of the Archives |

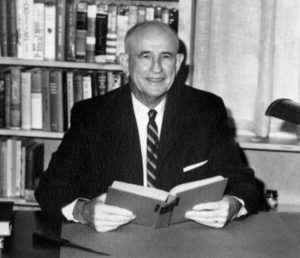

ViewHistory professor Fletcher M. Green directed over 100 dissertations Professors in the Department of History usually advise numerous graduate students, but few have had as much influence on graduate education as Fletcher M. Green, a Kenan Professor of History from 1927 until his retirement in 1968. Green, a specialist in the history of the American South, directed over 100 doctoral dissertations and 150 master’s theses during his time at UNC—and left a lasting legacy in the study of the American South. Because of his work with graduate students, “Fletcher M. Green has probably had a more far-reaching influence on the writing of Southern history than has any other man of his generation,” historian William C. Binkley once wrote. Indeed, at a time when interest in Southern history was on the rise, many of Green’s students rose to the top of their field. Well-known Southern historians Arthur S. Link, Dewey W. Grantham, George B. Tindall, and Paul M. Gaston all studied under Green. Green focused his own research on the Civil War and Reconstruction, but he also studied the American South more broadly. His first book, Constitutional Development in the South Atlantic States, 1776-1860 (1930), was based on the dissertation that he wrote at UNC under the direction of Joseph Gregoire de Roulhac Hamilton. Although some of Green’s interpretations would seem dated to a modern reader, Green did not share his adviser’s support for white supremacist movements. Rather, Green drew on his expertise in the history of Reconstruction to condemn the resurgence of white supremacy in twentieth-century North Carolina. Green was always willing to advise projects outside his immediate area of expertise. “One of Dr. Green’s most interesting qualities was that his students ranged the field of the old and new South—developing no central theme or pattern,” historian J. Isaac Copeland wrote. “So frequently students follow their director’s interest—all pursuing law, policy, slavery, agriculture, the small farmer or what have you—all working on various segments of thought with their basic interpretation being that of the director. With Dr. Green that was never true. He encouraged you to pursue your historical interest in your own way and with your own interpretation.” Dissertations that Green advised included topics as diverse as the Florida everglades, farmer organizing in the South, prohibition in Alabama, the 1912 presidential election, and the southern home front in the Civil War. Green’s willingness to let his advisees pursue their own interests was but one of his many qualities as an adviser, according to former student Paul Murray. Green, Murray recalled, was best defined by his “personal friendliness, patience, and perfectionism.” Occasionally, from the student’s perspective, his perfectionism did not seem so friendly. Describing Green’s feedback on his first dissertation chapter draft, Murray wrote: “This letter was accompanied by a returned manuscript literally torn to shreds. My first reaction was that [Green] had completely failed to grasp my meaning and I immediately wrote him to that effect. He never even answered that letter. As I studied the matter I realized he had been actually kind to me and that the only course for me was to rewrite the thing. This sequence with slight variations was repeated twice on the first chapter and at least once on every chapter in this study.” Although Green’s high standards could be daunting for Murray and other advisees, he helped them produce high-quality scholarship and obtain jobs at colleges and universities across the nation. Beyond his work as an adviser and teacher, Green helped to professionalize the field of Southern history. In 1934, he was among the founding members of the Southern Historical Association, an organization dedicated to taking an “investigative rather than memorial approach” to Southern history. He helped oversee the organization’s Journal of Southern History and served as organizational president in 1945. At UNC, Green also served as the Director of the Southern Historical Collection. After retirement, Green continued to publish and speak about the field of Southern history until his death at the age of 82 in 1978. Green’s papers, housed in the Southern Historical Collection, include many pieces of advice for his graduate students that have withstood the test of time. Here is a bit of wisdom for graduate students today: “You are writing to make clear to others. You have in the background all your reading and study. Others have only what you put down. Hence you want to make your manuscript tell clearly to the reader the whole story. In other words, try to make things stand out boldly.” Aubrey Lauersdorf |

| Graduate Student News |

ViewWhere in the world are UNC’s global history graduate students? If you ask Alyssa Bowen, a PhD candidate in History, to tell you about her travels for her dissertation research, you better have some time on your hands: she’s visited Belgium, Chile, Cuba, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States. For global historians like Bowen, it is not uncommon to visit archives on multiple continents to better understand processes that transcend nations or even regions. “Almost any project within any region can become a global project, pretty much from the late eighteenth century forward, just because there are so many interconnections in the world by that point that are documented and that are relatively easy to document,” Mark Reeves, a PhD candidate and global historian, explained. “Rather than just asking why did x happen here, at this time period, [you] ask the question: how did events around the world at this time affect x and how did x affect other places around the world? I think it’s as much about the frame of reference, and to some extent assuming connection rather than assuming disconnection.” As global historians, Reeves and Bowen focus on these interconnections. Reeves studies twentieth-century decolonization through the careers of four politicians in four different countries: the Philippines, Nigeria, India, and Syria. Bowen examines how global solidarity movements that opposed the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile transformed from radical, anti-imperialist movements into more human rights-oriented movements. Global historians often focus on previously neglected connections, according to graduate student Samee Siddiqui. “What I’m doing, and what I think most global historians do, is look at the movement of ideas, people, technologies, interconnections— and so looking at global interconnectivity and looking outside of the nationalist frame, and also, I think, the Eurocentric frame,” Siddiqui said. Siddiqui, who is still planning his dissertation research, will study twentieth-century Indian nationalist networks based in Tokyo and their interactions with Chinese, Filipino, and Vietnamese nationalist networks. Like his colleagues, Siddiqui must figure out how to narrow the long list of archives he could visit. Currently, he hopes to travel to archives in Japan, India, Pakistan, the United Kingdom, and possibly Hong Kong and Singapore. To do their archival research, global historians often need to master multiple languages. Siddiqui will need to read not only English, but Urdu, Japanese, and possibly Arabic and Malay. Bowen’s work on Chilean solidarity movements has required proficiency in French, German, Italian, and Spanish. Procuring funding to learn these languages can be a particular challenge for global history graduate students. Some global historians are able to secure Foreign Language and Area Studies (FLAS) grants from the U.S. federal government to support their language learning during the academic year. However, graduate students who are not U.S. citizens, like Siddiqui, are not eligible for this funding, and FLAS funds do not cover intensive summer language programs. “Research is often more costly for global historians because we need to learn a lot of languages,” Bowen explained. “If we want to go to Middlebury College or another program for the summer and do training, it would be helpful to have funding for something like this.” Global history’s broad scope also can pose particular intellectual challenges. “Something I learned from my M.A. thesis is that while the global framework is incredibly important for answering particular types of questions, it’s always a balance between [that framework and] getting a grip on the local,” Siddiqui said. “The best global history works I’ve read are excellent at looking at the global framework and global connections, and really teasing those out, but also never forgetting the importance of the local environment, local politics, local flavor.” Professors in the Department of History have encouraged their students to pursue projects that answer important questions about global connections and processes, despite some of the challenges. “I can’t speak highly enough of my committee members,” Reeves said. “Susan Pennybacker and Cemil Aydin especially challenged me to broaden my horizons and think bigger. When I came in, I was looking at a much more constrained project, and both of them really encouraged me to go bigger, and not wall off those connections.” Bowen is enthusiastic for the future of global history when she sees colleagues who do not identify as global historians increasingly look for global connections. “Since I started doing world or global history in my M.A. program in 2012, I’ve seen colleagues doing dissertations that have really used, even when they’re doing national histories, a very global approach. I think that’s encouraging.” Aubrey Lauersdorf Note from the Director of Graduate StudiesI am grateful to have an opportunity to serve as Director of Graduate Studies. The students continue to delight me with their fascinating projects, their insights, their cooperative spirit, and their enthusiasm—to say nothing of their very hard work. It is truly a pleasure to succeed someone as supremely competent and wonderfully innovative as Chad Bryant, and he has been quite generous with his time and expertise during the transition.

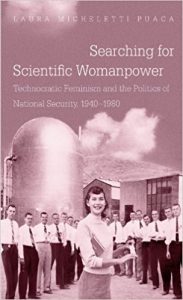

Laura Puacca’s article “The Largest Occupational Group of All the Disabled: Homemakers with Disabilities and Vocational Rehabilitation in Postwar America,” in Disabling Domesticity received the award for Best Article from the Disability History Association. Puacca was also awarded the Margaret W. Rossiter History of Women in Science Prize for the best book on the role of women in science for Searching for Scientific Womanpower: Technocratic Feminism and the Politics of National Security, 1940-1980. Jessie Wilkerson received the A. Elizabeth Taylor Prize for best article on southern women’s history from the Southern Association for Women Historians. I would love to include your news in upcoming newsletters and on our soon-to-be-debuted new web site. Please send information!

The promise of future historical scholarship has brought our students distinguished research opportunities as well. Alyssa Skarbek has been awarded a Fulbright-Hays Fellowship to conduct field research in Mexico. Lindsay Ayling has received a Fellowship from the UNC Graduate School, Robert Richard has received a Fellowship for research in Philadelphia, and Robert Colby received four short-term grants from a variety of institutions across the south for his work on the Civil War slave trade. Mary Elizabeth Walters has been named an Adams Fellow for the Public Humanities at Carolina Public Humanities. This is a small sampling. Please send news of your own accomplishments for the spring newsletter.

The History Department has been participating in the American Historical Association’s Career Diversity for Historians initiative. The Chicago fall workshop focused on ways to help departments train the next generation of history professors while also educating historians who can contribute actively to many other professions. As we continue participating in this project, we need advice from our alumni. What have you done as a professional historian outside the academy? What additional training would have been helpful? How has being a historian been important in your work? I would love to talk with you. Our graduate students remain central to the life of the department, providing not only award-winning teaching for our undergraduates but also enriching the intellectual life of the department. They engage with and reflect on faculty research-in-progress in their seminars, and present their own research in colloquia and in print. They have shown themselves to be a tremendous asset to all of the History Department’s projects, and the program continues to thrive because of their enthusiasm, insights, and commitment to understanding the past. Our department benefits enormously from their energy and thrives on their skills, despite the financial constraints that prevent our providing living-wage stipends and puts us (and them) at a disadvantage compared to our peer institutions. As Chad put it a year ago, “Our graduate students, in short, are the core of our department, and that, perhaps, is the most important thing to celebrate.” –Sarah Shields, Director of Graduate Studies |

| Undergrad News |

|

View

No items found

|

Gifts to the History Department

The History Department is a lively center for historical education and research. Although we are deeply committed to our mission as a public institution, our “margin of excellence” depends on generous private donations. At the present time, the department is particularly eager to improve the funding and fellowships for graduate students.

Your donations are used to send graduate students to professional conferences, support innovative student research, bring visiting speakers to campus, and expand other activities that enhance the department’s intellectual community.

|

To make a secure gift online, please click “Give Now” above.

The Department also receives tax-deductible donations through the Arts and Sciences Foundation at UNC-Chapel Hill. Please note in the “memo” section of your check that your gift is intended for the History Department. Donations should be sent to the following address:

UNC-Arts & Sciences Foundation

Buchan House

523 E. Franklin Street

Chapel Hill, NC 27514

Attention: Ronda Manuel

For more information about creating scholarships, fellowships, and professorships in the Department through a gift, pledge, or planned gift please contact Ronda Manuel, Associate Director of Development at the Arts and Sciences Foundation: ronda.manuel@unc.edu or (919) 962-7266.